There’s an old cliche that gets trotted out at weddings. It’s not politically correct, but it always gets some laughs. “A woman marries a man hoping he’ll change and become the incredible husband she knows he can be–and then he doesn’t. And a man marries a woman hoping that she’ll always be the girl he fell in love with and never change–and then she does.” Or something like that.

There’s an old cliche that gets trotted out at weddings. It’s not politically correct, but it always gets some laughs. “A woman marries a man hoping he’ll change and become the incredible husband she knows he can be–and then he doesn’t. And a man marries a woman hoping that she’ll always be the girl he fell in love with and never change–and then she does.” Or something like that.

Put the gender considerations aside for a moment. The saying is getting at something fundamental about human nature. We change too much and not enough. On this site, we probably overemphasize the ways in which people think they’ve transformed but haven’t–the inertia of existence (especially as it relates to the religious life)–just check out this post about high school. But the inverse is often the case as well, namely, that we tend to think we’ve not changed in ways that we actually have. The common denominator is always some concern about identity (and self-justification). We underline or leave out things in our life story depending on the narrative we are trying and/or think we need to spin. We are blinded by our biases, in other words, most of which are rooted in things we need to be true about ourselves in order to get by.

We’ve referenced David McRaney’s wonderful social science compendium You Are Not So Smart: Why You Have Too Many Friends on Facebook, Why Your Memory Is Mostly Fiction, and 46 Other Ways You’re Deluding Yourself a couple of times before. One of my favorite entries has to do with “consistency bias”. Most of McRaney’s explanation (below) has to do with the darker side of this phenomenon, i.e. the ways we think we are consistent and aren’t, but there’s also something genuinely hopeful about how we’re not always aware of the ways in which we have or haven’t changed. Meaning, it can be hopeful for those who are despondent about a lack of growth in some area of their lives. I believe the New Testament refers to this as “the left hand not knowing what the right hand is doing”. A few more lines of commentary at the bottom:

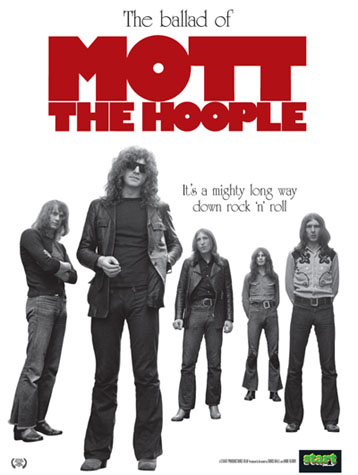

“I wish I’d never wanted then/What I want now twice as much” – Ian Hunter, “The Ballad of Mott the Hoople”

Imagine yourself in high school. What kind of person were you? Some obvious things come to mind–your awful haircut, those stupid shirts, the questionable taste in music. You sure were a dork.

If you were into a subculture, it is probably even more painful to see your old self. Were you an emo kid, a flannel-clad grunge fan, or did you trade Star Trek novels in your chess club? Whatever you were into at the time, it is likely you aren’t so into it now. You’ve probably learned how to tame your hair, which clothes are silly, and what music is truly good to you. You’ve figured out your personal politics, your taste in movies, what real friendship is all about. It’s as easy to see the differences in who you were then as it would be with two photographs taken now and then. Some differences, though, are hard to see. Scientists have shown you are not so smart when it comes to comparing your current mental world to the one you lived in years ago.

The psychologist Hazel Markus at the University of Michigan says when you receive new information that threatens your self-image, you react quickly to reaffirm your identity. The self is something psychologists have known from the beginning to be both consistent and changing. At any given moment, you guard your convictions and introspective conclusions, but the self you guard can shift from one social situation to the next. As the psychologist William James said in 1910, there are for any individual “as many different social selves as there are distinct groups of persons about whose opinion he cares.” Right now, all those selves are like the many surfaces of a prism; turn it one way or the other, and a different you is reflected back to the world. The consistency bias makes you think this prism has always been the same size and shape it is now, but it hasn’t.

In 1986, Markus published a paper that showed how malleable the self was and how oblivious to change you really are. The paper covered two decades of research. Back in 1965, Markus and his colleagues collected political opinions from a group of high school seniors and their parents. He then returned to the same people in 1973 and again in 1982 to see how their opinions might have changed. The questions ranged from the legalization of drugs to the rights of prisoners and the validity of war. As you might expect, the younger people’s attitudes changed a lot more between 1965 and 1973 than did their parents’, and overall these young attitudes became more conservative over the course of seventeen years. Markus showed how when you are young you are more open to changing your opinions. Your partisanship has yet to solidify into a personal philosophy. After gaining enough life experience, you begin to settle into a view of the world and establish your moral outlook. It seems like common sense, but when he asked the people in the study what they used to believe, only about 30 percent could accurately recall their old answers. Instead, they tended to say they used to have the same political ideas they currently subscribed to. If, for instance, they believe the death penalty was a legitimate punishment, they thought they had always believed this, even when they had said the opposite as a teenager…

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ELQOnEgzt-I&w=550]

Consistency bias is part of your overall desire to reduce the discomfort of cognitive dissonance, the emotions you feel when noticing that you are of two minds on one issue. When you say one thing and do another, the ickiness of feeling hypocritical must be dealt with or else you find it difficult to proceed. You need to feel that you can predict your own behavior, and so you rewrite your own history sometimes so you can seem dependable to yourself.

If your life story includes self-improvement, and you find meaning in change, you suppress consistency bias. At other times you simply desire certain parts of your autobiography to have unfolded in a pleasing way and can’t imagine having once been the sort of person you would argue with. If you are madly in love now, but once had your doubts, you simply delete the past and replace it with one less inconsistent with your present state. Older people tend to look at younger people as naive, and sometimes become amused when they see in them the same ignorance with which they once dealt. Sometimes they try to reason with the ignorance, as if to suggest it could be overcome with mere wisdom. This is consistency bias at work: believing if you knew then what you know now, things would be different. But people naturally change over time. Consistency bias is the failure to admit it.

How many of us have gotten stuck in a cycle of arguments around our need to prove that we’re being consistent, and the other person isn’t? They’re being unfair or upholding a double standard, or just plain irrational. I dare say that this desire to feel like we’re consistent accounts for quite a bit of heartache and estrangement in our lives. Admission of hypocrisy seems like a fate worse than death (for some people – not me of course).

The Christian faith is particularly helpful with this burden of consistency. Romans 7 paints a portrait of human life that is characterized by hypocrisy. Part of the freedom of the Gospel is the freedom from this bondage to consistency. We are not consistent, never will be and our schizophrenia causes all sorts of fallout, both relationally and personally. Jesus is the consistent one, not us, and the place he’s most consistent is in his love for stubborn hydra-like human beings (e.g. people who are dying to be saved, yet execute the savior). It’s good news for the inconsistent: permission to be honest about our conflictedness. Ironically, it may be the first step toward unity and integration.

COMMENTS

3 responses to “Are We Really Who We Used To Be?”

Leave a Reply

For what it’s worth, that’s Ronnie Wood singing “Ooh La La” for The Faces at the end of Rushmore. Not Ronnie Lane. He sang a lot of other great songs for them, but not that one.

Great post, DZ! I always go back to that great series put together by Michael Apted, the 7 Up Series (and the various ones later at intervals of seven years, recently 56 Up). It is so very interesting to see how people reconcile their past with their present (and I am sure with some future formulations thrown in for good measure), however I always found myself, in effect, not taking the meaning from it to heart. I, too, am an addict of consistency bias. I am constantly reworking my personal history. Revisionist history strikes again! (A piece of advice from a history student, every piece of history is revisionist, but don’t tell Academia!)

Thanks for the reminder.