The second preview from our publication Grace in Addiction: The Good News of Alcoholics Anonymous for Everybody. This one comes from the chapter on Step 3 (“made a decision to turn our will and our lives over to the care of God as we understood him”), pgs 64-69:

“Let me give you a truth that can make all the difference in the world: almost everything you think about doing to make something better is wrong and will only make that something worse… Trying harder doesn’t work.” -Steve Brown, Three Free Sins

Step 3 calls for a confrontation with the “unspiritual” life and the motivations that drive it, and as such, it is the first time that the program explicitly highlights the overarching and indissoluble tension between God and the self. As we find in one of the Big Book’s more infamous passages: “Selfishness and self-centeredness. That, we think, is the primary root of all our troubles. [We are] driven by a hundred forms of fear, self-delusion and self-seeking” (62). How do these factors play out in the human heart, and what is their role in perpetuating our doubts about God’s better will for our lives?

Step 3 calls for a confrontation with the “unspiritual” life and the motivations that drive it, and as such, it is the first time that the program explicitly highlights the overarching and indissoluble tension between God and the self. As we find in one of the Big Book’s more infamous passages: “Selfishness and self-centeredness. That, we think, is the primary root of all our troubles. [We are] driven by a hundred forms of fear, self-delusion and self-seeking” (62). How do these factors play out in the human heart, and what is their role in perpetuating our doubts about God’s better will for our lives?

In 1987, Janet Jackson released the hit single “Control.” She sang, “Control, never gonna stop/ Control, to get what I want/ Control, got to have a lot.” How many of us think that the key to individual success and happiness has to do with effort and internal volition? How many of us believe that willpower is the crucial factor in giving ourselves a life that is worth living? Popular advertising urges us to “never give up” or “just do it” or “make it happen”, and pop culture constantly emphasizes “action” as the way forward. These slogans not only exist in our culture, but also they seem wired into the DNA of human existence – and this is a dire problem. The Big Book puts it like this:

“Most people try to live by self-propulsion… Each person is like an actor who wants to run the whole show; is forever trying to arrange the lights, the ballet, the scenery and the rest of the players in his own way. If his arrangements would only stay put, if only people would do as he wished, the show would be great… What usually happens? The show doesn’t come off very well… He decides to exert himself more” (61).

What is meant by “self-propulsion”? Propulsion is the forward drive or inertia of an object that determines its movement from one point to another. Think of a propeller. It spins, and the movement enables it to push whatever it is attached to forward. According to this analogy, the individual is trying to act as the driving force behind her own life. Self-propulsion is the idea that I am the one who makes myself move, or “I am the master of my fate: I am the captain of my soul”, as the classic poem teaches students.

One does not have to look far to find expressions of this philosophy. I recently saw a billboard in an airport which showed a young Indonesian girl, standing in the midst of a rice paddy. Next to her, in bold red letters, were the words: “I AM POWERFUL.” The caption in no way described what I saw in the photograph. I saw two opposing ideas next to each other, yet separated by a vast gulf. There was assertion of power, inscribed in bold red letters. And then there was a child, a perfect portrait of all that is wonderful about the lack of power. I saw humility, weakness, beauty, and joy; lots of things, but not so-called “power.”

People that “live by self-propulsion” understand themselves to be their own source of power. Their success hinges upon their performance. Step 3 questions the efficacy of this philosophy.

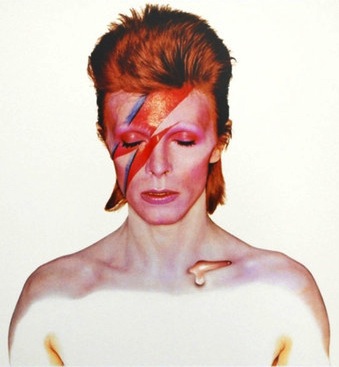

In order to do so, the Big Book likens the addict to an actor “who wants to run the whole show; is forever trying to arrange the lights, the ballet, the scenery and the rest of the players in his own way.” What is acting, and what does an actor do? Actors play the parts that are assigned to them. They assume the roles that are given to them. An actor prepares for his role by strict adherence to a script and occasional pointers from a director. But the actor we read about in the Big Book seems confused about his job description. If anything, he has very little interest in his own role, but an ambitious interest in the roles of the other players. What kind of acting is that? Bad acting at best.

There is a different name for the person who runs the show, who arranges the lights, the choreography, the scenery and the rest of the players. That person is called a “director.” The Big Book metaphor describes an actor who thinks he is a director. Can you imagine the chaos that would break out on set if one of the actors tried suddenly to usurp the director’s job? The chaos probably wouldn’t last very long, because the actor would soon be on his way out the door and in search of a new job!

The actor who is trying to play the director is busy functioning in an incorrect capacity, and no amount of effort and good ideas on his part can change that. Similarly, charitable actions that are motivated by self-interest are misguidedly conceived, no matter how many warm smiles and polite gestures introduce them. They take little actual account of the other’s well-being and, instead, view other people – even loved ones – as means to a personal end, which is usually an ill-conceived attempt at self- satisfaction and comfort. It is fair to say that our agendas often hamper our ability to be of service. In this respect, we see how love may quickly morph into manipulation.

In AA, people are understood to be actors, and “God is the director.” This is not meant as an insult so much as a straightforward description of the natural order of creation. Imagine further the insanity that would ensue if all of the actors in a show somehow got the same wrong idea about their roles, and they all started trying to control the production simultaneously, each with a different idea of how the story should be written.

In AA, people are understood to be actors, and “God is the director.” This is not meant as an insult so much as a straightforward description of the natural order of creation. Imagine further the insanity that would ensue if all of the actors in a show somehow got the same wrong idea about their roles, and they all started trying to control the production simultaneously, each with a different idea of how the story should be written.

Would it not be like the argumentative first cousins who got into a pushing match when their grandmother arrived for a Thanksgiving visit? As the fight broke out, one of them screamed: “She’s not your grandmother; she’s mine!” Warring narratives make for bad friendships, and a bunch of confused actors is not a pleasant image. Do you know any confused actors?

Malcolm Gladwell commented on this problematic mindset in an interview about his book Outliers: The Story of Success. He was asked to what extent his book was actually an attack on the philosophy of “rugged individualism, and the myth of American success.” His answer was illuminating:

“In some ways this book is somewhere between a corrective and a full-scale assault on the way Western society in general and American society in particular has thought about success over the last few hundred years. You know, we have fallen in love with this notion of the self-made man, of the rags-to-riches story, of the idea that if you make it to the top of your profession you deserve a salary of 20 million dollars a year because you’re the one responsible for getting to the top. Why shouldn’t you be richly rewarded? And that idea and that ethos has permeated virtually every way in which we think about achievement, and I think that that idea is completely false; it’s worse than false, it’s dangerous!”

The respective worlds of AA and Christian theology both agree with Mr. Gladwell. The “self-made” idea is, at least if not “dangerous,” still the very antithesis of spirituality. Of course, we might take it a step further, claiming that what Gladwell considers typical of “Western society in general and American society in particular” is in fact found in all cultures, though perhaps with varying sets of emphases. The idea of the self-made man is certainly far from unique, historically speaking.

A remarkably similar debate concerning spiritual self-propulsion occurred in the third century between a monk named Pelagius and a theologian named Augustine. Pelagius insisted that God had created people in such a way that their religious well-being was up to them. For him, everything centered on the attributes of self-discipline and unceasing effort. Though Pelagius admitted these traits were God-given, in practice his ideas allowed people to follow and defend their natural inclination toward being the masters of their souls. Augustine, like Gladwell, saw the fallacy of this reductionist and self-oriented train of thought. He knew that such a philosophy left little room for failure, and therefore no room for grace and the activity of God. The self-will approach was labeled a heresy by the early church, for it would have destroyed the need for the absolution upon which the Christian faith centered. Why would God, after all, create individuals in such a way that they would no longer have any need for Him? Step 3 does a wonderful job of separating the spiritual wheat from the well-intentioned but romantic chaff of the “self-made man”. The Big Book puts it like this:

“Above everything, we alcoholics must be rid of this selfishness. We must, or it kills us! God makes that possible. And there seems no way of getting rid of self without His aid. Many of us had moral and philosophical convictions galore but we could not live up to them, even though we would have liked to. Neither could we reduce our self-centeredness much by wishing or trying on our own power. We had to have God’s help…We could wish to be moral, we could wish to be philosophically comforted, in fact we could will these things with all our might, but the needed power wasn’t there. Our human resources, as marshaled by the will, were not sufficient; they failed utterly. Lack of power, that was our dilemma.” (62, 45)

The philosophy of self-propulsion and self-direction fails in its attempt to create happiness. In fact, it often creates the exact opposite of the thing it intends: chaos and tragedy instead of peace and contentment. For this reason, AAs are fond of saying: “My best thinking got me here [to a state of destitution and alcoholism].”

Order your copy of Grace in Addiction today!

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IMzmVcjSLUc&w=600]

COMMENTS

4 responses to “Cracked Actors, Self-Propulsion, and the Will of God”

Leave a Reply

Let’s face it – that Neil Diamond song is pretty phenomenal.

Great song, yes. I can tell Neil Diamond has been a broken man…though I do not know his story. His words speak about things only people broken by love know.

Thank you for this piece. You have put to wise words what I have only ruminated about. Tears and sighs are all I’ve only been able to get out about the matter. I would like to read this book, though I am not a recovering alcoholic (but would have been if the darn stuff didn’t make me so sick).

Let’s have a nation-wide audition for the Director of the World title! Let’s let the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob head it up (as if we “let him” be in charge). We will all see ourselves ‘miss the mark’. Then Jesus Christ will show up…thanks be to God.

Have mercy, Lord, for I cannot stand to be an actor in any other play (including mine) but your own!!! Amen.