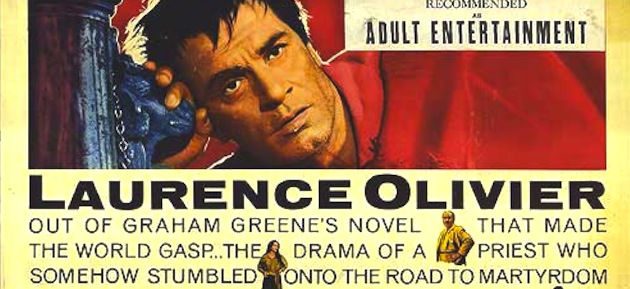

Here begins a week-long, three-part series on Graham Greene’s faith opus, The Power and the Glory, exploring his use of paradoxical realities of “this bloody land.” Through his “whisky priest,” the outlawed and only man left to administer the sacraments, Greene captures a world wherein the power is in the weak, and the glory is in the mire.

That’s another thing altogether—God is love. I don’t say the heart doesn’t feel a taste of it, but what a taste. The smallest glass of love mixed with a pint pot of ditch-water. We wouldn’t recognize that love. It might even look like hate. It would be enough to scare us—God’s love. It set fire to a bush in the desert, didn’t it, and smashed open graves and set the dead walking in the dark. Oh, a man like me would run a mile to get away if he felt that love around.

Lying beside the lieutenant that has been sent to end his life in two short days, the nameless “whisky priest” uses these words to describe the nature of a privated people in a Christ-haunted world. It is a world wherein its objects are skewed intimations of its eternal and perfect image, a world that of its own beckons salvation, in the presence of what’s absent, in its own sin-rife contortions of the proper ideas of things. It is a world devoid of man-made sacraments, and yet rich with the sacramentality of creation, without the help of religious relics. Greene depicts a catholicity (small “c”) to Christian truth through its evocations in the common elements of the world. Within these elements, nothing is not fair game in its pointing to Christ.

The nameless whiskey priest is nameless because he is an Everyman. He is criminal, lover, sinner, drunkard, father, coward. He is you. He runs to stay alive, and yet finds his path blocked and re-directed despite him. Not able to give Mass, not able to remain with a parish, not able to carry with him the fabric of his faith–he is unmanned. His pursuers are the Red Shirts, who have outlawed the Catholic faith and, in the name of strong-armed power for the overpowered poor, have waylaid all priests except one. In his squalid attempts to elude, he knows he is bound to a Calvary that awaits at road’s end.

On this outwardly godless road, the reader finds everything pointing to God.We see this pointing in the continual references to the image of God. As the priest has compassion on his yellow-fanged Judas figure, the nameless half-caste, carrying him on his mule, he ponders on these warped figures, these dejected children of Adam: “Something resembling God dangled from the gibbet or went into odd attitudes before the bullets in a prison yard or contorted itself like a camel in the attitude of sex…and God’s image shook now, up and down on the mule’s back, with the yellow teeth stick out over the lower lip.” This is Greene’s sacramental anthropology, an image fractured, the disordered ‘attitudes’ of man from their created telos. Despite his own pariahhood, though, he is still an evocation of his great Lover. In an Augustinian sense, the very acts of sinful nature are not foreign posturings of ruthless godlessness, but instead a good desire disordered. This is how the priest describes to the pious woman the pleasure of sexual passion taking place in the prison cell next to them: “Well, we are not saints, you and I. Suffering to us is just ugly. Stench and crowding and pain. That is beautiful in that corner—to them.”

This sacramentality of creation twisted upon itself leads Greene to envision the anthropological community in the banquet of criminals. After weeks on the run, the best semblance of community that the priest finds is in the prison cell, awaiting his discovery and death. The occasional sacramentality of his office as Catholic priest—the Host, the cassock, the kissing of the glove—becomes seemingly arbitrary, and takes a backseat to the catholic sacramentality of common prisonship:

Again, he was touched by an extraordinary affection. He was just one criminal among a herd of criminals…He had a sense of companionship which he had never experienced in the old days when pious people came kissing his black cotton glove.

What does this affection amongst criminals point to? It seems to indicate both the communion of suffering that comes from the Image broken, as well as indicating the prison-unto-death that is the bound will. The priest is no different; what sacrament once made a distinction between his sacred office and the needy communicants is now wholly leveled to the prison floor of the common prisoner. The priest’s own criminality (he frequently says “I am a bad priest”) summons the true nature of the priesthood. It is one of servitude, wherein the priest serving is no better than the communicant served, where, as he tells the lieutenant, he offers something that is pointing beyond him. It is that love in the pint pot of ditch-water:

What does this affection amongst criminals point to? It seems to indicate both the communion of suffering that comes from the Image broken, as well as indicating the prison-unto-death that is the bound will. The priest is no different; what sacrament once made a distinction between his sacred office and the needy communicants is now wholly leveled to the prison floor of the common prisoner. The priest’s own criminality (he frequently says “I am a bad priest”) summons the true nature of the priesthood. It is one of servitude, wherein the priest serving is no better than the communicant served, where, as he tells the lieutenant, he offers something that is pointing beyond him. It is that love in the pint pot of ditch-water:

‘That’s another difference between us. It’s no good working for your end unless you’re a good man yourself. And there won’t always be good men in your party. Then you’ll have all the old starvation, beating, get-rich-anyhow. But it doesn’t matter so much my being a coward—and all the rest. I can put God into a man’s mouth just the same—and I can give him God’s pardon. It wouldn’t make any difference to that if every priest in the Church was like me.’

COMMENTS

2 responses to “The Paradox of The Power and the Glory, Part One: The Criminal as Parishioner”

Leave a Reply

Graham Greene is a great author. I just finished his “Brighton Rock,” which is about the undeserved mercy of God.

But to get more on track with the post, I think of the Judas character in The Power and The Glory like the character of Kichijiro in Shusako Endo’s Silence, which is about a couple of Jesuit priests sneaking into Japan during the 17th century persecution of Christians there. It is a heart rending little novel, for which Graham Greene himself had had regard. In the story, Kichijiro constantly acts like a traitorous worm, but always crawls back to one of the priests to beg for confession and absolution. The whole relationship between the Jesuit and Kichijiro is so similar to the relationship and interaction of the priest in the Power and the Glory and the half-caste. There is a wonderful part where a peasant infant gets baptized in a shoddy hut. I’d recommend Silence if you liked The Power and the Glory. Below is a quote from the book where the Jesuit main character reflects on the baptism of a peasant infant, conducting in a shoddy hut in the middle of nowhere:

“This child also would grow up like its parents and grandparents to eke out a miserable existence face to face with the black sea in this cramped and desolate land; it, too, would live like a beast, and like a beast it would die. But Christ did not die for the good and the beautiful. It is easy enough to die for the good and beautiful. It is easy enough to die for the good and beautiful; the hard thing is to die for the miserable and corrupt-this is the realization that came home to me acutely at that time. ”

Thanks,

-Brett

[…] is more rigorous and unforgiving than any religion in its call for total commitment to the cause, a standard of which all people (and animals) must necessarily fall short. If I, a sinful man (or […]