Since last we checked in, not two but four episodes of PZ’s podcast have been published! To download/listen, simply click on the title of each.

Episode 65: One Message or Two?

I seem to keep getting the question, ‘What is your message for non-disillusioned people?’

I seem to keep getting the question, ‘What is your message for non-disillusioned people?’

You may be on to something in relation to older, disillusioned types — for people who’ve hit major road-blocks. But what about people who are building their lives, people who are shaping their identities and selves? Do you really expect them to respond to appeals that they should give it all up, stop, and take a taste of non-being? I mean, come on!

It’s a core question.

This talk came to me as a result of a conversation last week in Salisbury with someone older and wiser who posed the same question. Is there one message for young people and a second message for the, uh, middle-aged?

I thought about the famous Religious Young: Zwingli, Francis, Ignatius, Clare, Pachomius, Catherine, Paul, Our Lord. There are tons of them. Tons.

I believe it’s the same message: a sort of ‘No Exit’ “Ye must be born again” combined with “Love one another”. It’s sort of got to be the same message. Otherwise, the Church would be saying “Build Me Up, Butter Cup” (The Foundations), only to switch on you later, when “The Levee’s Gonna Break” (Dylan). That sounds dumb to me.

Episode 66: Altars by the Roadside

I found something! I found a perfect sermon for everybody: that one message (not two) for the young and for the old.

I found something! I found a perfect sermon for everybody: that one message (not two) for the young and for the old.

It comes from ‘Mark Rutherford”s The Revolution in Tanner’s Lane (1890), pp. 266-268, in which the ancient and elderly preacher, The Rev. Thomas Bradshaw, delivers a sermon in the presence of a young husband and father, George Allen; and George is entirely addressed by the words of the old man. “It was the first time George had ever heard anything from any public speaker which came home to him, and he wondered if Mr. Bradshaw knew his history.”

What Mr. Bradshaw actually says, you’ll have to look up. It shouldn’t surprise you that Ecclesiastes enters into it, but Ecclesiastes for “My young friends” (268).

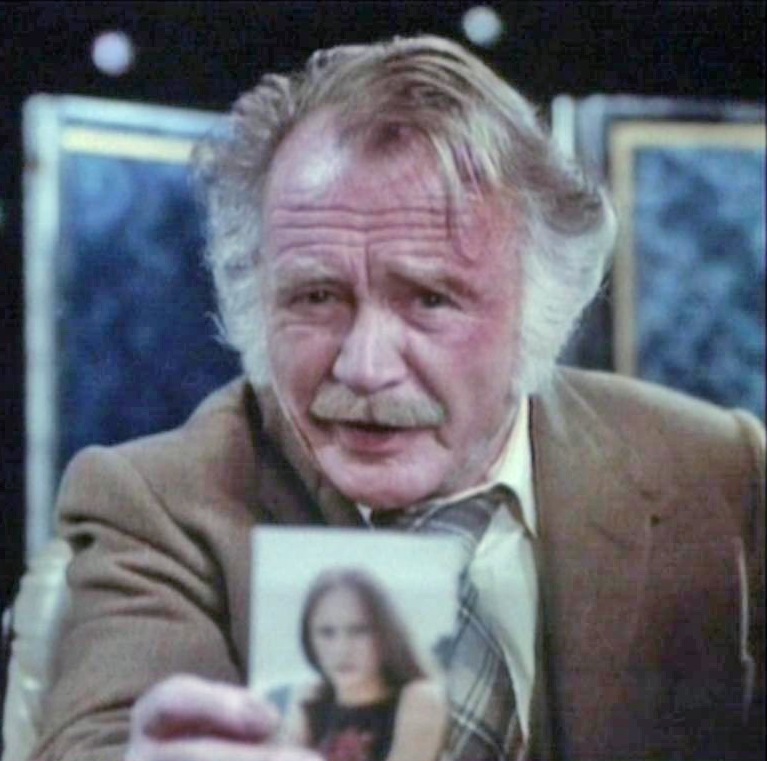

This is a podcast about wisdom in relation to the “young.” It ties back to dear old Bernard Quatermass, elderly savant in Nigel Kneale’s “Quatermass” (1979), who actually and successfully saves the entire younger generation of England, Scotland and Wales! You’ll see.

Episode 67: The Inward Voice, Pt. 1

We talk about “voice” these days and the need to express our voice. I agree with that: everybody has a voice.

Exactly what is your voice? What does it consist of and where is it found?

This talk attempts to locate the personal voice that speaks inside you. No surprise that I locate a fulcrum kind of voice in the American novel of inwardness: By Love Possessed. Not much of a surprise, either, that Romans, Chapter Seven delineates a ‘typical’ human voice, nor that Paul’s Teacher majored on the inward voice of human beings.

The English actor Freddie Jones contributes something, too, in the speaker’s search for his voice. That’s from Count Dracula and his Vampire Bride (1973).

I hope this podcast can help in your own discovery, and commissioning, of that voice which is your very own inward conversation.

Episode 68: The Inward Voice, Pt. 2

I think there is no more realistic voice in 19th-Century English literature than the voice of ‘Mark Rutherford’, whose real name was William Hale White. White wrote six mighty novels under the nom de plume of ‘Mark Rutherford”, and nobody knew. Someone finally “outed” White, later in his life, but not until it was too late for his wife to have read any of her loving husband’s books. Nobody knew that he was living in his novels.

William Hale White required his mask.

William Hale White required his mask.

For all kinds of reasons, he required the mask.

The result was a series of novels concerning the biggest possible issues, yet acted out in the smallest possible settings (i.e., the “world” of provincial Dissent, or non-Anglican evangelicalism, which would soon morph mostly into forms of Christian unitarianism). The voice of the author is extremely emotional in a most distilled and ‘pursed’ way — I realize this is extravagant praise — and also panoramically associative in the way that Philip Wylie commends so warmly in Finnley Wren (1934). (You’ve got to read The Revolution in Tanner’s Lane ! “No Doubt About It” – Hot Chocolate.)

Today I’m talking about the masks we wear: What Lies Beneath. Drop the mask, and let your inward voice be heard. Once your mask is dropped, you really won’t have to force it any longer. The song will come out on its own.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bb_OEaHfWII&w=600]

COMMENTS