It’s undeniable that the Locavore Movement has been gaining momentum for years now, and that having a small backyard vegetable garden is no longer a reliable counterculture identifier. (You only grew kale from seed?) The phenomenon of buying local, eating local has settled in stride with the contemporary (and arguably ancient biblical) values for the neighbor, the gift of good land; the public awareness of a dissipating ozone layer, the (apparent) dissatisfaction with gargantuan supercenters and megaplexes; and so its arrival spawned a fecund harvest of lo-fi documentaries and hipster publications–until it became the thing, rather than a thing. It’s what good coffee has been for a while–you’re actually countercultural if you still scoop from a Folger’s tin.

It’s undeniable that the Locavore Movement has been gaining momentum for years now, and that having a small backyard vegetable garden is no longer a reliable counterculture identifier. (You only grew kale from seed?) The phenomenon of buying local, eating local has settled in stride with the contemporary (and arguably ancient biblical) values for the neighbor, the gift of good land; the public awareness of a dissipating ozone layer, the (apparent) dissatisfaction with gargantuan supercenters and megaplexes; and so its arrival spawned a fecund harvest of lo-fi documentaries and hipster publications–until it became the thing, rather than a thing. It’s what good coffee has been for a while–you’re actually countercultural if you still scoop from a Folger’s tin.

It was interesting, then, to see a contrarian article in the Atlantic about the movement, written by a guy who writes about food, hastening the public to rethink its effects. Who can argue with this? Apparently, the Locavore’s biggest mistake is rooted in its own burgeoning success–the urban homesteader has become insufficient as solely a gardener, and has found newer niches to peruse, one of them being the inner-city care of livestock (chicken, goats, birds, rabbits). This appendage to the movement has brought forth the proposed deregulation of animal slaughter, meaning that animals could be raised and slain on one’s own property, without overarching authoritative measures.

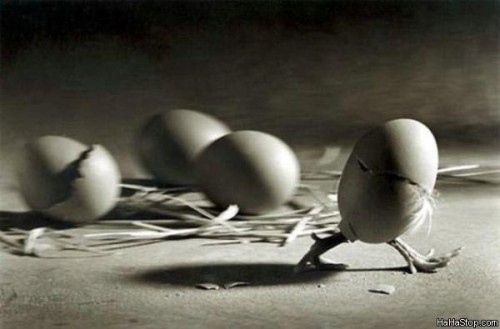

McWilliams’ commentary to keep animal slaughter at a “graceful distance” is as intriguing as the trend itself. The raising of livestock in the Age of the Blogger has proffered immense amounts of material as to what actually happens when people today pick up a hobby. It seems that there is an immense magnetism to the aesthetic of a form, in this case that of the eat-what-you-grow backyard subsistence farmer, but a lack of substantive energy to keep it going. The gardener is willing, the flesh is weak. McWilliams cites numerous novice butchers who have caused repulsive suffering upon their chickens, simply by not knowing how to care for and kill them. Imagining a freshly home-butchered rosemary-laden chicken thigh with a corn-mango summer salad is not enough to make it happen rightly. It’s not that this idea is bad, or that one’s yearning for its fruition is selfishly motivated–in fact, these are valiant efforts. Instead, it seems more that these interests are merely that: attention-deficient hobbies for the (attention) deficient modern human.

It’s a vulgar article in pieces, but McWilliams brings to light the distrust one might have with movements as such, in their capability to slip people away from their situational reality by way of illusory and transient passion. Though passion is necessary, in the way it illuminates energy and purpose, it is not sufficient, and its deficiency shows here. Goats will always be goats, but passion is so quickly father to neglect.

Blogs kept by urban farmers confirm ignorance. An account by a San Francisco farmer about killing a backyard chicken for the first time — which she openly admitted to having no idea how to do — has the homesteader wringing the chicken’s neck repeatedly, only to find it still breathing. In the end, this women “settled on covering her nostrils with my fingers” and suffocating the bird. Needless to say, an inexpertly slaughtered animal experiences immense suffering.

A second problem with deregulating animal slaughter is that any policy making it easier for backyard enthusiasts to raise and process their own meat is automatically a policy that establishes the preconditions for more animal neglect — the kind of neglect that locavores have long fought to end in their vehement opposition to factory farming. Proof, once again, comes from none other than the advocates of backyard slaughter themselves.

Oakland animal farm bloggers offer a litany of horrors already perpetuated on animals kept on urban farms. Readers can learn about a mother rabbit succumbing to heat stroke (and leaving behind seven kits), a chicken who dies from eating glass, ducks succumbing to rat poison, and chickens killed by invading possums — all mishaps unique to backyard animal husbandry. The East Bay Urban Agriculture Alliance argues that a deregulated environment will be “better for animals.” Given their own accounts, though, it’s a hard claim to stomach.

Assessments outside of the movement are just as dire. The Oakland neighbor of a backyard goat “farmer” reports listening to a goat die an agonizing, four-hour death after eating from the garbage can. A rabbit keeper was documented keeping twenty-one rabbits in absolute squalor. The abused rabbits were birthing stillborns, riddled with parasites, and suffering from broken limbs.

Such abuse is what we expect to hear from heady exposes of factory farming. But, as these anecdotes suggest, localized operations are by no means immune to systematic animal abuse. And because of the deregulated organization, local animal welfare groups have made it clear that they have no way to monitor such abuses.

…

Advocates promote backyard slaughter as part of the larger goal of “food literacy.” But, given such troubling contradictions, it strikes me more as a program designed to perpetuate confusion in order to fulfill a romantic idea of small-scale animal husbandry. Kids ask honest questions, and I for one am in no position to explain why it’s okay to kill the “meat rabbit” but not the pet rabbit.

Locavores have beaten the odds and taken their message to the streets. Today, to say that something is “locally sourced” is to rightfully earn a culinary badge of sustainability. By extending their mission from the plant to the animal world, however, those who want us to eat local risk reducing this hard-earned victory into nothing short of a bloody mess.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply