Wes Anderson’s The Darjeeling Limited was released on Criterion two weeks ago, and if you know what’s good for you, you’ll add it to your Christmas list post-haste. It’s a beautiful edition of a beautiful movie that boasts surprising, albeit inadvertent theological resonance. I’m serious. Even if you find Wes’ films overly stylized or precious (or whatever people say about him – I obviously worship the guy), or if you wrote the film off as a tedious feature-length tribute to Satyajit Ray, I encourage you to look again. There is much to appreciate here.

Wes Anderson’s The Darjeeling Limited was released on Criterion two weeks ago, and if you know what’s good for you, you’ll add it to your Christmas list post-haste. It’s a beautiful edition of a beautiful movie that boasts surprising, albeit inadvertent theological resonance. I’m serious. Even if you find Wes’ films overly stylized or precious (or whatever people say about him – I obviously worship the guy), or if you wrote the film off as a tedious feature-length tribute to Satyajit Ray, I encourage you to look again. There is much to appreciate here.

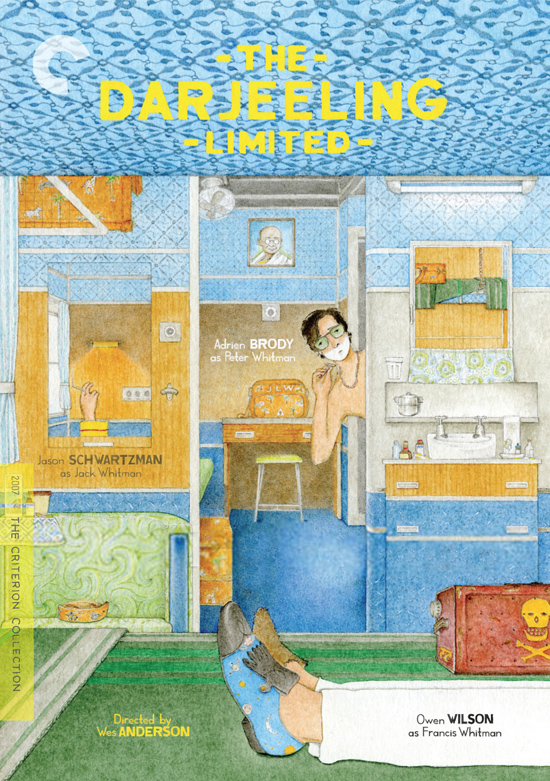

The film tells the story of three privileged brothers, the Whitmans, and their “spiritual journey” to India following the sudden death of the father and the prolonged absence of their mother. As we find out, each sibling has chosen to “deal with,” i.e. distract himself from, his pain in a different self-destructive fashion: Francis (Owen Wilson) through suicidal recklessness, Peter (Adrian Brody) through emotional isolation, Jack (Jason Schwartzman) through co-dependency, and all of them through (absurd) substance abuse. They are portrayed as a remarkably dysfunctional yet lovable bunch, arrested in their development to a comic degree, yet clearly doing the best they can with the hand they’ve been dealt. That is to say, they’re looking for healing. Sort of.

Unfortunately, things don’t quite work out that way. Through a series of ridiculous events, they end up making things much worse for themselves, until they are kicked off their train, and their assistant quits. The Whitmans are ready to give up and go home. Which is where this first clip opens [warning: slight language]:

[youtube=www.youtube.com/watch?v=CX6qAFy0fd0&w=600]

The accident represents the turning point in the film. The chattering and bickering finally stops and the Whitmans are drawn outside of themselves, at last. Flannery O’Connor once wrote:

“I suppose the reasons for the use of so much violence in modern fiction will differ with each writer who uses it, but in my own stories I have found that violence is strangely capable of returning my characters to reality and preparing them to accept their moment of grace. Their heads are so hard that almost nothing else will do the work. This idea, that reality is something to which we must be returned at considerable cost, is one which is seldom understood by the casual reader, but it is one which is implicit in the Christian view of the world.”

It is no stretch to say that this dynamic is evident in The Darjeeling Limited as well. The Whitmans spiritual journey begins where they think it ends. The death of the boy brings them into powerful and unavoidable contact with their own grief, and suddenly all of their attempts, including the spiritual ones, to circumvent their suffering dissolve into thin air. The baptismal imagery which follows isn’t just window-dressing:

[youtube=www.youtube.com/watch?v=eNFtMb2vFBM&w=600]

[youtube=www.youtube.com/watch?v=104C1zZxSEw&w=600]

So… as the film aptly demonstrates, setting out to have a spiritual experience doesn’t always work – in fact, it tends to backfire. Breakthroughs of these kind cannot be planned with laminated itineraries; as much as we or the Whitmans wish we could, we are powerless to engineer change in ourselves – God happens to a person, and often it looks/feels like a disaster. It may even be a disaster. The ultimate expression, of course, being the Crucifixion.

The wonderful thing about The Darjeeling Limited is that it doesn’t settle for simply lampooning Western attempts at commodifying Eastern spirituality (although it does that handily). Instead, it gives us a glimpse of genuine spirituality and healing, the sort which, fortunately for us, cannot be divorced from (a theology of) the cross. This is good news for the Whitmans and it’s good news for us. We may find all sorts of creative ways to medicate ourselves and stave off death, but resurrection is coming. The birth pangs are painful, but the hope is real. Don’t take it from me…

Martin Luther’s Heidelberg Disputation

Thesis 18 – It is certain that man must utterly despair of his own ability before he is prepared to receive the grace of Christ. We must despair of our own ability! But there is hope beyond our abilities!

Thesis 21 – Only through suffering and the Cross can a sinner come to know God. Suffering is the only clear indication of God’s operation on the sinner. Knowledge of God comes when God happens to us, when God does himself to us. We are crucified with Christ (Gal. 2:19).

COMMENTS

6 responses to “The Darjeeling Limited and The Theology of the Cross”

Leave a Reply

It looks terrific.

I've been meaning to go back and re-watch this one, and now, thanks to this post, I think I'll have done so by the close of the week. Thanks DZ!

“God happens to a person, and often it looks/feels like a disaster.”

That’s so true. And in the film, which essentially chronicles three brothers trying to escape their situations, it takes the death of a small boy to burst their bubbles of narcissism. This happens rarely and is always done to you, not by you. But when you are able to get outside yourself, what freedom!

I love this movie.