The penultimate installment in our series of entries from Judgment & Love, here is Bonnie’s chapter. Again, J&L is a collection of 35 true-life stories illustrating the powerful truth that when love is shown in the face of deserved judgment, lives are changed. To order your copy at the reduced price of $10, go here or click on the button at the bottom of the post.

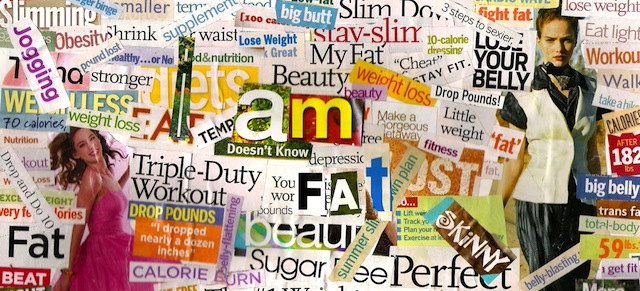

Like most teenagers living in developed countries, I worried about the way I looked. I knew I wasn’t fat, and even though I wasn’t quite as thin as some other girls, it didn’t really bother me at all since there were always other characteristics that made me feel good about myself—good grades, a lot of self confidence, a happy personality, and good friends. My body was never a very large part of my identity until I lived abroad and gained twenty-five pounds over six months. Somehow, that set off a siren in my head that something was not okay: I was “fat.” Not knowing what to do (and never having been on a diet before), I resorted to desperate measures to remove this “bad” part of my self-image: I developed an eating disorder.

Like most teenagers living in developed countries, I worried about the way I looked. I knew I wasn’t fat, and even though I wasn’t quite as thin as some other girls, it didn’t really bother me at all since there were always other characteristics that made me feel good about myself—good grades, a lot of self confidence, a happy personality, and good friends. My body was never a very large part of my identity until I lived abroad and gained twenty-five pounds over six months. Somehow, that set off a siren in my head that something was not okay: I was “fat.” Not knowing what to do (and never having been on a diet before), I resorted to desperate measures to remove this “bad” part of my self-image: I developed an eating disorder.According to Biological Psychiatry, 80% of women in the United States exhibit signs of an eating disorder at some stage; between 1-5% of adolescent women meet the criteria for diagnosis of an eating disorder, including an estimated 19-30% of college-age women. I became a statistic.

Some girls revel in their ability to manipulate how much they eat. When I was in high school, I remember a girl triumphantly told me she had only eaten three mints over an entire day; I thought that was the stupidest thing I had ever heard. Another girl told me about how to manipulate your throat to make yourself gag; that grossed me out. When I became desperate enough, however, these strategies seemed less strange and more “effective.” I thought I could stop once I had lost the twenty-five pounds. But I didn’t.

At this point you might say, “Oh, but you didn’t know better.” Of course I knew better. I was a Christian, and I knew my identity shouldn’t be determined by how I looked: I am “a child of God,” a “temple of the Holy Spirit,” and free from the bondage of sin and death. Children of God shouldn’t have to worry about mortal bodies that will eventually turn to dust. Temples of the Holy Spirit should certainly be presentable to the Lord. Christians who have been freed from bondage shouldn’t have obsessive- compulsive disorders. But knowing these things didn’t really change my behavior—in fact, it made me feel worse about myself. I would be reminded of my identity in God and the promise of God’s deliverance during my morning quiet time, and four hours later at lunch I would either not eat, eat too much, or count the calories in my salad with tuna (no dressing), and feel like a complete failure.

At this point you might say, “Oh, but you didn’t know better.” Of course I knew better. I was a Christian, and I knew my identity shouldn’t be determined by how I looked: I am “a child of God,” a “temple of the Holy Spirit,” and free from the bondage of sin and death. Children of God shouldn’t have to worry about mortal bodies that will eventually turn to dust. Temples of the Holy Spirit should certainly be presentable to the Lord. Christians who have been freed from bondage shouldn’t have obsessive- compulsive disorders. But knowing these things didn’t really change my behavior—in fact, it made me feel worse about myself. I would be reminded of my identity in God and the promise of God’s deliverance during my morning quiet time, and four hours later at lunch I would either not eat, eat too much, or count the calories in my salad with tuna (no dressing), and feel like a complete failure.I talked to counselors and other Christians, had accountability partners, read books, and prayed that something would change. I had already lost the twenty-five pounds, maybe more, and looked terrible. But I didn’t and couldn’t stop, and I hated myself for it. (I figured that God probably didn’t hate me, but He wasn’t going to be entirely happy with me until I shaped up.)

At some point in college I took an English class called The English Bible. (I was a Christian. Taking a class called The English Bible meant no reading. It was senior year.) I decided to write my paper on Romans 1-12 because it had substantial content but was shorter than most of the Gospel accounts. I read those chapters over and over and over again. At some point, something clicked. While I had focused on the parts of the Bible about how I ought to be in order to motivate myself to change, I had neglected the parts that discuss how I actually am: “I do not understand what I do. For what I want to do I do not do, but what I hate I do. …For what I do is not the good I want to do; no, the evil I do not want to do – this I keep on doing.” (Romans 7.15, 19) For the first time, I read something in the Bible that described how I was actually feeling for months and months. Instead of making me feel even further from God than I already felt, the Bible actually made me feel understood. Instead of reminding me about who I ought to be, it reminded me of who I really am.

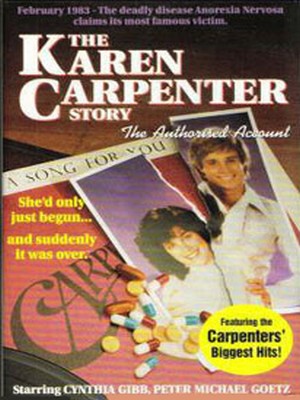

[youtube=www.youtube.com/watch?v=yF7f4SSV6ms&w=600]

I read the next chapter: “Therefore, there is now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus. . . . For I am convinced that neither death nor life, neither angels nor demons, neither the present nor the future, nor any powers, neither height nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God that is in Christ Jesus our Lord.” (Romans 8.1, 38-39)

Boom. Thanks to my English paper, this message finally made sense to me. God imposes no oughts; instead, He completely understands and accepts me. There was no fine print: I didn’t even have to reduce the thousands of things I ought to be down to fifty before I would be loved. Jesus had taken away the oughts, which is why I was (and am) still a Christian in spite of all the messed up things in my life (see Romans 7:24).

I would like to say that immediately after that experience I was “delivered” from my eating issues, but that was not the case. It took many more months and a seemingly completely unrelated incident to remedy my eating issues. I realized, though, that I was loved not for how much promise I could show fulfilling my oughts. Christians are not people with the “potential” to do what they ought to do. Christians are people who know they are loved even when they aren’t who they ought to be.

COMMENTS

3 responses to “Me, My Oughts, and I”

Leave a Reply

Wow! What a “Gospel” home run!

But. Having grown up in the South, yet in an agnostic, liberal family, I saw then 50+ years ago, and still do today, this same self-forgiveness incarnate in what I’ve called the evangelist’s Get Out Of Sin Free card. Like alcoholics, abusive sinners live lives that brutalize themselves and those around them, get absolution, and return to abuse; rinse and repeat. I am affirm the true righteousness of the Christian forgiveness in this story, but must note that it can be used falsely to excuse great and recurring wickedness.

Thank you both to the author and Stewart for offering insight. Verses in Proverbs and Psalms which draw attention to the fear of the Lord come to mind. Prov 1:7 The fear of the Lord is the beginning of knowlege, but fools despise wisdom and instruction. Author Ed Welch points out loyalty and trust as key characteristics of this fear. I have struggled with one eating disorder ten years ago and another type now. I appreciate the truth of the article and the caution of this comment, though I hope to be a witness to it personally in my own conduct, belief, and honor.