The other day, I listened to an NPR Speaking of Faith interview with the late Jaroslav Pelikan entitled The Need for Creeds. For those of you who don’t know of this radio program, its sort of like the website Beliefnet.com, but with Harris Tweed and allusions to Kafka. This seemed to be one of the more difficult subjects for the host, Krista Tippett, because, as she mentioned throughout the interview, the very nature of a creed—a confession of what is believed—goes against the enlightened sensibilities of “modern people.”

The other day, I listened to an NPR Speaking of Faith interview with the late Jaroslav Pelikan entitled The Need for Creeds. For those of you who don’t know of this radio program, its sort of like the website Beliefnet.com, but with Harris Tweed and allusions to Kafka. This seemed to be one of the more difficult subjects for the host, Krista Tippett, because, as she mentioned throughout the interview, the very nature of a creed—a confession of what is believed—goes against the enlightened sensibilities of “modern people.”

“Isn’t faith, at heart,” she asks Dr. Pelikan at one point, “about mystery, which can never be perfectly comprehended?”

The subject of Alisa Harris’ article “Having None of It,” in which she describes someone who is emblematic of a new demographic she calls the “Nones,” would, one imgaines, affirm this sentiment. Her subject,

“…knows he’s not Lutheran. He doesn’t go to church. He considers himself Christian, which he says means “a strong relationship with God” and regular prayer, but he is not wholly convinced that Jesus died for his sins. The story resonates with him, “But I don’t know. I just feel that at the end of it all when you’re at the pearly gates, I won’t be shocked if it’s not exactly like it was written in the Bible… I have a lot of faith, but no religion.”

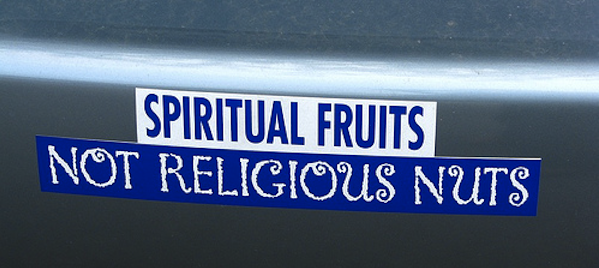

This conception is ubiquitous: from “faith communities” to “faith journeys,” the idea of faith existing independently of a specific content underlies the concept of being “spiritual but not religious,” with the added appeal of sounding enlightened and open-minded. Nothing says, “Hey, I’m not a fundamentalist” like shrugging your shoulders. As Ms. Harris writes:

“I don’t know,” but “maybe”: [are] the bywords of the Nones. Now, nobody can deny the appeal of (supposed) freedom afforded by this way of thinking: freedom from a specific creed or religion, freedom from dogmatic assertions about truth and falsity and freedom from having to judge. But this is where the Law/Gospel has something unique to say to this idea, because what is being touted as “spiritual but NOT religious,” is, according to the Bible, the essence of being religious but not spiritual. What looks like open-minded, generous spirituality is actually religious slavery to the need to create God in one’s own image.

Far from being a-religious, this supposedly new, kinder, gentler spirituality is simply neo-Hinduism, argues Lisa Miller in an article from Newsweek (ht WHI), entitled “We Are All Hindus Now.” She writes:

Thirty percent of Americans call themselves “spiritual, not religious,” according to a 2009 NEWSWEEK Poll, up from 24 percent in 2005. Stephen Prothero, religion professor at Boston University, has long framed the American propensity for “the divine-deli-cafeteria religion” as “very much in the spirit of Hinduism. You’re not picking and choosing from different religions, because they’re all the same,” he says. “It isn’t about orthodoxy. It’s about whatever works. If going to yoga works, great—and if going to Catholic mass works, great. And if going to Catholic mass plus the yoga plus the Buddhist retreat works, that’s great, too.”

Roughly 2000 years ago, the Apostle Paul ran into a group of people who were similarly “spiritual,” and had this to say to them:

“Men of Athens, I perceive that in every way you are very religious. For as I passed along and observed the objects of your worship, I found also an altar with this inscription, ‘To the unknown god.’ What therefore you worship as unknown, this I proclaim to you.”

And what was it that Paul proclaimed? The content of the one Faith we now find explicated in the historic creeds; Jesus Christ, who “for our sake was crucified under Pontius Pilate; he suffered death and was buried. On the third day he rose again in accordance with the Scriptures; he ascended into heaven and is seated at the right hand of the Father. He will come again in glory to judge the living and the dead, and his kingdom will have no end. . . “

Contrary to a vague, mysterious description of how to be “spiritual,” the Bible takes great pains to clarify exactly what it means. In the Bible, being “spiritual” does not mean having some sort of ecstatic or vague, sentimentalized notion of the divine, rather it centers on a confession. Contrast the contemporary understanding of “spiritual,” with how the Apostle Paul explains the concept to the church in Corinth:

“The natural person does not accept the things of the Spirit of God, for they are folly to him, and he is not able to understand them because they are spiritually discerned.. . .”

And what are these things that are discerned? Are they new and exciting ways to “get closer to God,” or perhaps a better way to find inner peace or a feeling of connection to the earth and all living things? No. What is discerned is the same thing that was revealed to Peter when, answering Jesus’ question, “who do you say that I am,” replied, “You are the Christ, the Son of the living God.”

As always, there is more to be said on this, but for now, I’ll leave you with this excerpt from the interview with Dr. Pelikan; enjoy!

I mean, all of us are, in one sense or another, pupils of Socrates. John Stewart Mill said humanity cannot be reminded often enough that there was once a man named Socrates, and that’s right. But there are no temples built to Socrates. Nobody ever wrote the “B Minor Mass” in honor of Socrates, because he calls upon people to learn and therefore to be honest with themselves, but he does not call upon them to take up their cross and follow. And both he and Jesus died for what they believed. But Jesus died in the conscious commitment to the salvation of the world. And so wherever the message is preached and brought in whatever language it comes from, the language it comes to and the culture into which it penetrates must, at some stage of its maturation, learn to answer yet again the question: “Who do you say that I am?” Because the “you say” in that question is the culture in which we live. He’s not asking, “Who does the fourth century say that I am?” when it was writing in Greek. That’s important, because without that we wouldn’t be where we are. But, at some point, you have to be who and what you are in the only culture in which you’re ever going to live, the only century in which you’re going to live and die, and, in that century, you have to answer with whatever linguistic and philosophical equipment you have, you have to answer the question: “Who do you say that I am?”

COMMENTS

11 responses to “Religious, Not Spiritual”

Leave a Reply

Nice post, Jady. The BAD VICAR (to whom Mockingbird introduced me) does a really fun send-up of a modern couple that is "spiritual but not particularly religious."

Hey Jady. A few years ago, when I was in my last year of EFA (Education for Apostasy, a lay theological program run by Sewannee), the leader had us all listen to that NPR interview with Pelikan you mentioned.

In general people in the class had a really good response to it — mostly, as far as I could see, because it left you feeling intellectual and bookish and way cultured (as NPR always does), but also because Pelikan managed to suggest every possible reason that the Nicene Creed had value except the two reasons that count:

(1) The Nicene Creed is a series of claims which, if true, are of earth shattering importance.

(2) The Nicene Creed is in fact true.

Instead, he talks about:

* How human beings in general have a psychological need for creeds as such

* How the Nicene Creed is great because saying it makes him feel like a part of a big family stretching back in time

* How saying the Creed is good because it serves as a badge identifying him as a contemporary member of a group.

* How it is part of Western Civilization and is one of our great cultural achievements, along with things like Bach's Mass In B Minor — and that you can still be an atheist and appreciate that.

* How it serves as a great interest to him in his job as a professional historian

* How it is so beautiful and powerful when it is sung — its liturgical value, and how when you hear it like that you want to love other people.

For one very brief moment he begins to flirt with the idea that it might be true, but he then quickly slides into its value as performance art.

Go Solstice?

Did I hear that right?

I once saw a car with the following two bumper stickers:

"My Karma Ran Over My Dogma"

and

"I Don't Eat Anything That Has A Face."

Seemed a little ironic. I guess that even the "spiritual" have their "dogma", and usually buckets full, when it comes to the things they really care about.

Excellent post!

I'm hearing the same thing, Todd…

I'm pretty sure its saying "solstice." I think I'll re-post that commercial with the title "Christmas has jumped the shark"

Ahhh…the Gap, a wonderful example of how commercialism gives lip service to everything for the sake of its own net income. Though, to be fair, the CEO might be an especially devout Unitarian. 😉

here comes the sun, dodododo, here comes the sun, dodododo, here comes the sun, and I say… Merry Solsticemas!