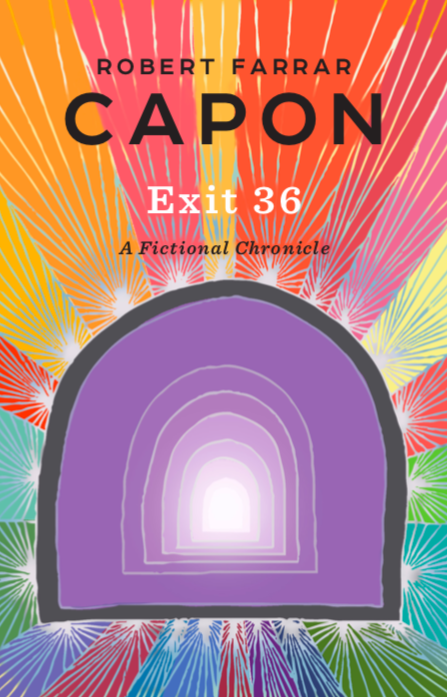

A huge thank you to Chad Bird for this eloquent preface to our recent republication of Robert Farrar Capon’s Exit 36. Order your copy today!

In the early days of December, I crawl up into my attic, step over a couple of rafters, and take a deep breath to blow a year’s worth of dust off a long cardboard box. On the side, written in faded black marker, is the name, Barbara. Then down we go, man and box, back over the rafters, back down the ladder, and into the family room, where the annual ritual begins. Cut the tape, open the box, and piece by piece, begin to remove and organize the contents. A wobbly, three-legged stand. A green, six-foot pole. And a pile of prickly, plastic limbs that look like the ugly cousin of mother nature’s evergreen beauty. After an hour or so of disentangling and reassembling—and probably a drink or three—the conical tree stands tall and proud, ready to have its green plainness festooned with the winking colors of Christmas cheer.

But this is no ordinary tree. It has a stubborn streak. Weave a hundred strands of bright lights through its greenery, let a thousand happy ornaments swing and sing from its limbs, and the tree itself will stand there like a tight-lipped choir girl who won’t join in “Joy to the World.” It’s Barbara’s tree—a gift she gave my family shortly before she drove to south Texas, shut off the engine in a city park, and swallowed the darkness inside her by swallowing a bottleful of pills. And now her tree stands there, our family’s visual memory of her and the friendship we shared. And try as we might to make her tree as beautiful, sparkling, and happy as we can, it’s hard not to see those branches decorated and dripping with tears.

But this is no ordinary tree. It has a stubborn streak. Weave a hundred strands of bright lights through its greenery, let a thousand happy ornaments swing and sing from its limbs, and the tree itself will stand there like a tight-lipped choir girl who won’t join in “Joy to the World.” It’s Barbara’s tree—a gift she gave my family shortly before she drove to south Texas, shut off the engine in a city park, and swallowed the darkness inside her by swallowing a bottleful of pills. And now her tree stands there, our family’s visual memory of her and the friendship we shared. And try as we might to make her tree as beautiful, sparkling, and happy as we can, it’s hard not to see those branches decorated and dripping with tears.

I think this December, and maybe every December after that, I’ll try something new. I’ll pull a chair up in front of Barbara’s tree, open Exit 36, and begin to read Robert Capon’s words aloud. The whole story, beginning to end. Let them wash over the room, the tree, me, the memories, the regrets, the unanswered and unresolvable questions. Then, when I’m finished, I’ll close the book and prop it up against the base of the tree. Because if there’s a story this tree needs to hear, my family needs to hear, and all who have lost Barbaras of their own need to hear, it’s the one you now hold in your hands.

Robert Capon does in this book what he always does with unparalleled skill: he stirs the ultimate questions of life into the seemingly un-ultimate, daily grind of characters’ lives who make a royal mess of their relationships, friendships, and vocations. A priest who’s so done with life he ends it all by driving his car into a concrete embankment at 80 mph. Another priest—the narrator—who, when he isn’t trying to get to the bottom of the reasons for his colleague’s suicide, comforting the widow, or producing a brilliant theology about the reconciliation of all things in Christ, is playing with the fire of attraction to the dead man’s lovely mistress. Sprinkle in some brief but lively excurses about the nastiness of church politics, food and drinks, and life on the east coast, and you have the priceless gem called Exit 36. So is this a novel or a theological work, a narrative or a sermon? Yes, and more. Put suicide, ministry, adultery, eschatology, gospel, Jesus, and curvy mistresses all onto the literary table, pour some wine, settle into your seat, and gaze in wonder at the feast that only Capon could prepare with such brilliance, wit, and profundity.

Capon is one of those rare birds among Christian authors. He actually takes seriously the fact that, when God was deliberating how best to unveil the profoundest mysteries of the world, he jettisoned philosophical treatises, systematic theologies, and Q & A catechisms. He chose instead to sit us children down on the front porch, light his pipe, and say, “Kids, let me tell you a story.” A story full of naked people and talking snakes, polygamous kings and street-smart prostitutes, giants and blind men and prophets smelling like they crawled out of a fish. When God wants us to know something, to really know something, to stake our very lives on the truth of it: he tells us a story. He punctuates the narrative with prayers and psalms, proverbs and sermons, scolding letters and hair-raising apocalypses, but these only serve to spice things up a bit. And as we hear the story, we are swallowed up by it, sting at its pains and laugh at its jokes, and—strangest of all—realize the story we are hearing about others turns out to be the story of ourselves.

Capon is one of those rare birds among Christian authors. He actually takes seriously the fact that, when God was deliberating how best to unveil the profoundest mysteries of the world, he jettisoned philosophical treatises, systematic theologies, and Q & A catechisms. He chose instead to sit us children down on the front porch, light his pipe, and say, “Kids, let me tell you a story.” A story full of naked people and talking snakes, polygamous kings and street-smart prostitutes, giants and blind men and prophets smelling like they crawled out of a fish. When God wants us to know something, to really know something, to stake our very lives on the truth of it: he tells us a story. He punctuates the narrative with prayers and psalms, proverbs and sermons, scolding letters and hair-raising apocalypses, but these only serve to spice things up a bit. And as we hear the story, we are swallowed up by it, sting at its pains and laugh at its jokes, and—strangest of all—realize the story we are hearing about others turns out to be the story of ourselves.

In this way, Exit 36 falls smack dab in the middle of the biblical genre. More than the story of one month in the life of a parish priest who’s juggling counseling, preaching, flirting, drinking, and exploring his own mortality, it’s the story of the God standing behind the veil of the story. The God who isn’t bound by the tick-tocking, chronological flow of our lives from diapers to dentures. The God for whom the future is not “out there” or the past “back there,” but for whom everything that ever has been, is, or will be, is simply, his very own Today. And that Today, that God-Day, is the day that enfolds all of our days, that sucks them into its vortex and transforms them into what it is. More importantly, that Today is the day of salvation, of the reconciliation of everyman and everything in the crucified and resurrected Christ, who holds the whole kit and caboodle inside his own skin.

The suicide? Reconciled. The widow? Reconciled. The mistress, the gossipers, the gravedigger, the children, and the storytelling priest? All reconciled. Not one after the other. Not when they zipped up and quit frequenting cheap hotel rooms. Not when they confessed and toed the line. Not in that millisecond of righteous regret before the vehicle slammed into the concrete. Not in yesterday’s repentance or tomorrow’s amendment of life. But all in that grand and all-compassing Today of the Lamb slain from the foundation of the world. They all fit into his scars. What’s more, they’ve all been there from the get-go, from the pre-Genesis days, before creation, before the fall, before the last curtain call when trumpets blast and glorified bodies start popping out of graveyards like champagne corks. Above all those historical moments stands the Lamb, holding together all humanity in the reconciliation that’s handcuffed to no clock or calendar, but free in the never-beginning and never-ending Today of salvation.

This December, when I pull up a chair in front of Barbara’s tree, and read this book aloud, those are the thoughts that’ll be frolicking inside my head. What really matters is not her divorce, her depression, her closetful of skeletons or her heart empty of hope—what matters are not those dark and fragmented moments of her day-to-day existence, but the God of love who wrapped her in his arms before she even arrived in this broken life.

This December, when I pull up a chair in front of Barbara’s tree, and read this book aloud, those are the thoughts that’ll be frolicking inside my head. What really matters is not her divorce, her depression, her closetful of skeletons or her heart empty of hope—what matters are not those dark and fragmented moments of her day-to-day existence, but the God of love who wrapped her in his arms before she even arrived in this broken life.

Capon ushers us into the story where Barbara and me, you and the priests, and this whole wide world of jacked up, navel-gazing, time-bound and sin-worn creatures are already included in Today’s party where the Lamb pours and refills drinks for us all, where the Father is tickled pink with us, and where life in abundance is all there is to be found.

You can find Exit 36 in our online store and on Amazon!

You can also find Mockingbird editions of Robert’s other books: More Theology & Less Heavy Cream, The Man Who Met God in a Bar, and Bed & Board.

COMMENTS

One response to “Preface by Chad Bird to Exit 36: A Fictional Chronicle”

Leave a Reply

KA BOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOM!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! Makes me want to speak in “tongues”

Thank you Chad.