Despite a seldom-interrupted lifelong habit of weekly church attendance, I have difficulty recalling the content and personal impact of more than about a dozen sermons. I may be a poor auditory learner in any case, and my lack of recall does not reflect on the homiletical abilities of my many friends who spend hours every week on their sermons.

I do remember a sermon on 74th Street when I was in high school during which nearly every sentence was punctuated with “Christ is king.” I remember a sermon in the same church when I was in college, in which the preacher made impossibly learned and moving comparisons between the burial of Patroclus and the burial of our Lord. I remember the first sermons I heard in Japanese, when the strangeness of the Gospel in a new language helped convince me anew as a young man that it was all true. I remember a bizarre sermon in the late 1990s on 43rd Street in which the preacher opined “Euclid or Plotinus? Euclid and Plotinus. Euclid and Plotinus!”

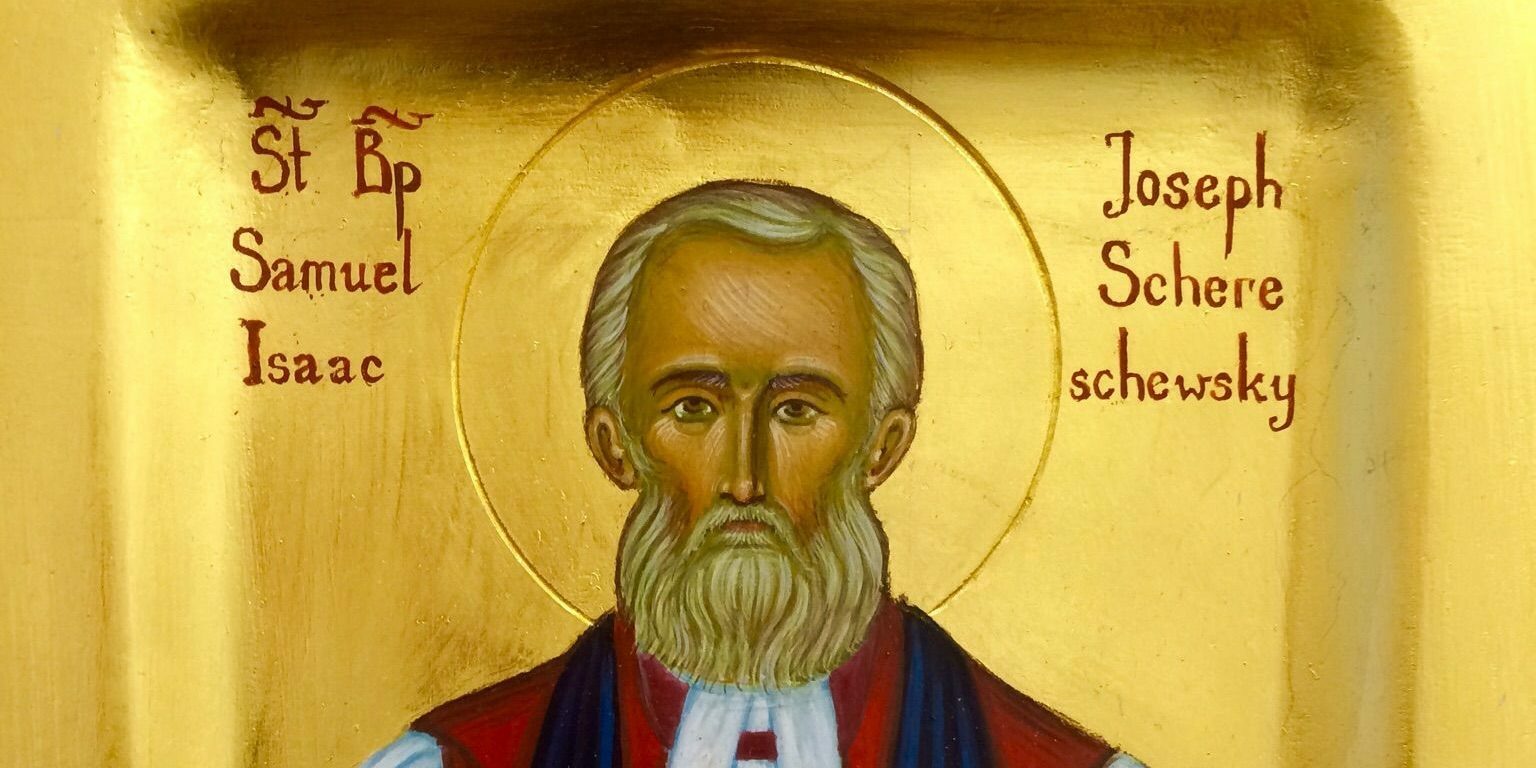

The sermon that changed my life was not an especially eloquent one, and I was fifteen when I heard it. I had been earning my first paycheck at $4.25 an hour at a local bookstore, saving up for a car I would buy after my sixteenth birthday. I made coffee and sandwiches, stocked the shelves, and attended to the sales register on weekends and during the summer. The bookstore is still there, and so is the church a block and a half away where I started attending weekday services on my lunch hour. I chanced one October Saturday to be one of five or six in the chapel at Trinity Church, Easton, when the commemoration was of Samuel Isaac Joseph Schereschewsky.

Samuel was born in Russian Lithuania in 1831 and orphaned as a child. An older brother raised him and supported him as he undertook Talmudic studies in the Jerusalem of the North, intending to become a rabbi. It was during rabbinical study, at about 15, that he discovered a copy of the New Testament in Hebrew. He was baptized at 24 after emigrating first to Germany for theological study, and then to the United States. In New York City, he studied at both Union Theological Seminary and the General Theological Seminary, and he was ordained to the priesthood in the Episcopal Church in 1859. The polyglot who already spoke Yiddish, German, Russian, Polish, English, and Hebrew taught himself Chinese, and moved with his wife to Peking in 1862 to undertake Bible translation. He returned to the United States in 1877 to be consecrated at Grace Church, Broadway, as Bishop of Shanghai.

Samuel was born in Russian Lithuania in 1831 and orphaned as a child. An older brother raised him and supported him as he undertook Talmudic studies in the Jerusalem of the North, intending to become a rabbi. It was during rabbinical study, at about 15, that he discovered a copy of the New Testament in Hebrew. He was baptized at 24 after emigrating first to Germany for theological study, and then to the United States. In New York City, he studied at both Union Theological Seminary and the General Theological Seminary, and he was ordained to the priesthood in the Episcopal Church in 1859. The polyglot who already spoke Yiddish, German, Russian, Polish, English, and Hebrew taught himself Chinese, and moved with his wife to Peking in 1862 to undertake Bible translation. He returned to the United States in 1877 to be consecrated at Grace Church, Broadway, as Bishop of Shanghai.

The episcopate lasted only seven years, as an attack of sunstroke incapacitated him for the rest of his life. He spent the next twenty-five years as a paralytic, sitting in the same chair each day, with the use of only one hand and then two fingers—a kind of nineteenth-century Jean-Dominique Bauby. It was with those fingers that he completed new translations of the Bible into several dialects of Chinese, becoming the most influential individual translator of Hebrew and Greek into Chinese who has ever lived. All while sitting in the same chair, without the power of speech, but with nearly unparalleled powers of language in his mind and a heart so changed by faith that he wasted his life for the sake of the Gospel.

By the end of the sermon, which can only have been six or seven minutes long, I said to myself I want to be like him. I’ve never had the chance to tell the preacher, now long retired and a gentle presence in his community, what his words did for me.

I do not encourage others to emulate my emulation. But for my part, I have since arranged my life in ways that serve a singular purpose of giving focused time each day—no matter what my circumstances or other duties—to the preservation and dissemination of religious knowledge. My eyes get tired, my fingers get stiff, my posture has likely suffered, and I probably annoy my friends with what seem like obscure or quixotic undertakings. I will never be Samuel Isaac Joseph Schereschewsky, but the example of his single-mindedness and purpose was defining for me as I have become an adult Christian who wants to share the depth and breadth of what has been given to him. Do I really need to find that book and make a PDF so that one or two other people might read it? Yes. And that one? Yes. The pearl is of such a great price that one must sell everything to acquire it.

My young adult awe remains intact about the influence of this man’s life and work. It is hard to know how many Christians there are in China—perhaps 40 million—but the Bibles they read were largely in some measure the gift of this Lithuanian Jew.

Sam returns to my mind at key stages when I start something time-consuming or (in my best hopes) impactful. In the wake of painful throat and nose surgery last month, reduced to a raspy voice, and forced in a way to rest against my nature, I went back to Sam. One of his early translations was the monumental Mandarin Book of Common Prayer, published with his friend John Shaw Burdon in Peking in 1872. The text taught a generation of new Chinese Christians how to order their lives around the Psalter, how to marry, how to ordain, how to bury their dead, how to baptize their children, and how to celebrate the Holy Communion. The book itself is now impossibly hard to find—an easy victim for library theft, as at Yale Divinity School—and I have been chasing copies for my entire adult life. When I finally found one, I decided to sink myself into it until it had been unpacked again for anyone with an Internet connection. The books are brittle now, and I have lived with each of their 800 pages for a season of my life.

Unlike Sam, I can’t speak a word of Chinese. (I can surprise you with Yiddish, however, on the right day of the week.) But my childhood Japanese is still strong enough that I can keyboard things in Chinese for a labor-intensive line or two at a time; and the alchemy of turning a piece of paper into a graphic file accessible across any platform requires little language skill. Convalescence gave me the focus to spend time with the work of a lifelong inspiration. Popsicles and Prayer Books turn out to be good investments at such a time.

Is the game worth the candle? Time and Google Analytics will tell, but the free provision of Christian literature in Chinese seems as urgent a matter this year as ever. The general silence of the western churches today toward our siblings in Jesus wherever else they are is, in the case of mainland China, often an acceptance of the reverse gunboat diplomacy now practiced by Beijing.

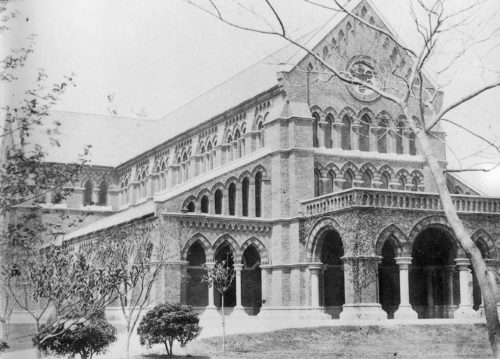

Notwithstanding a strange new détente with the Vatican, Chinese Christians are living in conditions manipulated directly by their state. The last foreign missionaries in China, members of generations of families from Virginia and Oxbridge who had given their lives to service in that field, were expelled between 1949 and 1953. Our hospitals, schools, convents, publishing houses, and churches were closed. Christian denominations were abolished and amalgamated in 1958 in a kind of destructive ecumenism. Cultural Revolution and re-education purged the ranks of clergy and lay leaders. The Anglican cathedral in Shanghai was converted into an auditorium before being abandoned to urban decay; the seventeenth-century Russian Orthodox mission offices and church complex were bulldozed and turned into a parking lot for an embassy. Martyrdom was easy for a season. The Christian community planted by Schereschewsky and his friends seemed likely to be gone in the twinkling of an eye.

Shi Meiding, Zhui yi – 近代上海图史

Despite this crippling demolition of religious structure—and with the distance of sixty years from the spasms of revolution—Christianity is now thriving against contrary odds. Even the municipal government of Shanghai acknowledged the historical and touristic value of the old cathedral, restored it at extraordinary expense, and has (if grudgingly) reopened it for regular worship.

Will the Jewish Bishop who created the Chinese Bible in his weakness-made-strength continue to speak the words of the Gospel of peace from his grave-sleep as I whisper and try to make myself heard in flower-shops and supermarkets? He will while I have the time and ability to help him. It is an odd work of grace to have met a dead man when one was in high school, for him to have shaped me across the centuries, and to be able to seize the chance to work with him a little. It is an odd work of grace to see the Church thrive in places so inimical to it. I am very thankful.

COMMENTS

4 responses to “Popsicles and Prayer Books”

Leave a Reply

The connections here are permanent, fleeting, universal, human: this is one reason Mockingbird is a unique place of thought and action…

Beautiful testimony to the power of example in ordering our lives and those of others through our witness. The BCP ground such hope.

I would love to know the source of the beautiful icon! He’s one of my favorites.

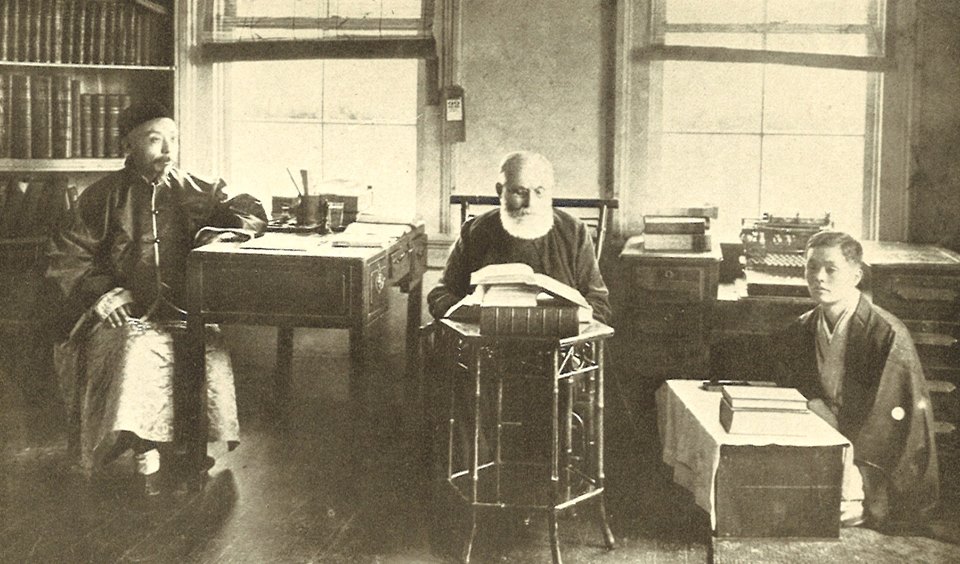

What a wonderful piece. Where did you find that photo, and who are the three people in it?