This reflection comes to us from Cole Deike.

We have bloody imaginations.

As an opposite to the bloody imagination, I think of the Pixar animated movie Up. Early in the film, there is a montage of a young couple falling in love with one another. In one of the scenes, the young couple lays on a blanket and gazes up at clouds that breeze across the blue, summer sky. There is no audio of their dialogue, but they are pointing at specific clouds and talking about their shapes: this one reminds me of this animal, that one reminds me of that animal, and so on.

And suddenly, as a lightning bolt strikes her affections, the young woman becomes captivated by the thought of babies. In an instant, her imagination transforms all the nebulous, shapeless clouds into babies. This adorable scene sheds magnificent insight onto the human imagination: the eye sees what the imagination desires. The Apostle Paul might say that they were looking at the clouds with “the eyes of their hearts” (Ephesians 1:18).

I think of the old hymn: “This is my Father’s world. The birds their carols raise, the morning light, the lily white, declare their Maker’s praise…he shines in all that’s fair; in the rustling grass I hear Him pass, he speaks to me everywhere.” The hymnist has been so captivated by God’s beauty that his imagination sees, hears, and experiences deep realities of God in the everyday stuff of life.

I think of Saint Augustine. Supposedly, his biographer reported, while he entered his final season of life, Augustine requested the Psalms to be copied out and hung on his wall where he could gaze at them on his deathbed. And apparently, his imagination was so steeped in the Psalms that his speech sounded like the Psalms. He had a Psalm’ish imagination: the Spirit-given ability to see deep realities of God in and through and behind the ordinary stuff of life.

I wish my imagination was more like that.

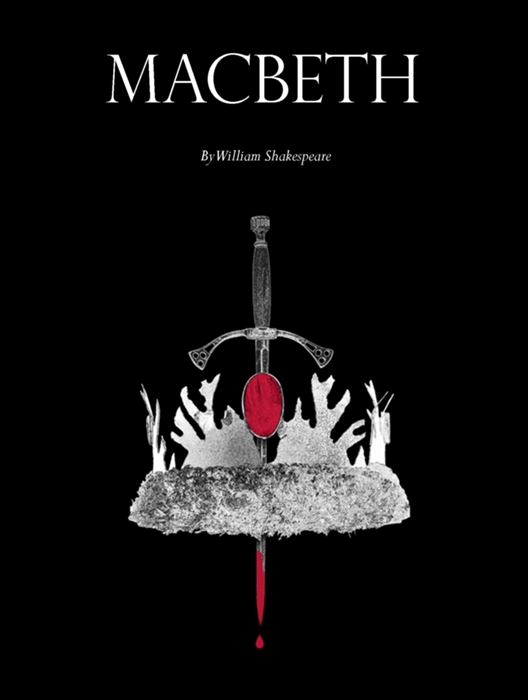

My imagination is a little more bloody, a little more like Lady Macbeth’s in the old shakespearean play. She got everything she wanted. She successfully manipulated her husband; he successfully carried out the murder of the king. He obtained the title of King of Scotland. She obtained the title of Queen of Scotland.

But then, the shape of her imagination begins to change, to morph. She begins to imagine blood on her hands; she begins to hear the constant, internal noise of guilt. And her inner-dialogue of condemnation ultimately leads her to a water faucet where she washes and scrubs, washes and scrubs, until she cries out: “Out damned spot!… All the perfumes of Arabia could not make these hands clean!”

But then, the shape of her imagination begins to change, to morph. She begins to imagine blood on her hands; she begins to hear the constant, internal noise of guilt. And her inner-dialogue of condemnation ultimately leads her to a water faucet where she washes and scrubs, washes and scrubs, until she cries out: “Out damned spot!… All the perfumes of Arabia could not make these hands clean!”

In one film adaptation, the scene’s horror darkens. As she scrubs her hands under the faucet, nothing comes out. And then the faucet turns on. And what finally comes out isn’t water but more blood. What comes out isn’t the cleansing agent she so desperately needs but more guilt.

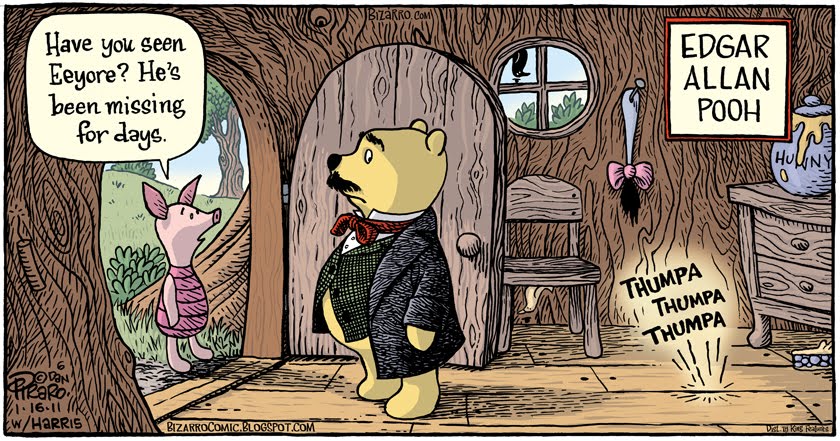

I think also of the narrator from The Tell-Tale Heart by Edgar Allan Poe. After murdering his neighbor in the middle of the night, he begins the cover-up of his crime. He rips up the floorboards of the home, he conceals the body and, shortly after, two policeman arrive to investigate the scene. The narrator is so confident in his work that, in an attempt to appear calm, cool, and innocent, he positions a few chairs directly over the buried body to sit and have a casual conversation with the policeman.

And then, the shape of his imagination begins to change. Like Lady Macbeth, his mind starts to hear noises beyond the grasp of his ears. The noise begins with a slight ringing and, as it grows and grows and grows and grows, his head begins to pound and, as it aches and aches and aches and aches, he begins to believe that the noise is actually the beating heart of his neighbor’s corpse.

The heart beats and beats and beats and beats and, unable to live beneath the weight of his bloody imagination, the narrator tears up the floorboards, confesses his guilt, and reveals the body to the policeman.

What Shakespeare and Poe have described in their writing is the plight of the Christian: what if people knew what I did? In our little small groups, in our coffee shop conversations, in our Sunday morning services, we all hear heartbeats under our floorboards and wonder: what if people knew what I did?

I think of King David, who lived with both the bloody imagination of Queen Macbeth and the Psalm’ish imagination of Saint Augustine. King David committed some awesomely terrible things, sins which cast shadows of such length and width that they dwarf the narrator in The Tell-Tale Heart. While one of his soldiers was fighting for King David’s safety in battle, David manipulated the soldier’s wife into his bed. He impregnated her. He attempted to cover it up. And failed. And failed again. And after his attempts failed, he ordered the soldier to be sent to the front of battle where he would be surely killed. And he surely was. Eventually, God sends a prophet and, after much prophetic prying, David confesses.

Like the narrator in The Tell-Tale Heart, he rips up the floorboards, exposes the corpse, and writes Psalm 51: “Have mercy on me, O God, according to your steadfast love; according to your abundant mercy blot out my transgressions. Wash me thoroughly from my iniquity, and cleanse me from my sin!”

If you have an imagination like mine, shaped and formed mostly by the internal noise of personal guilt, take Psalm 51 as a humble starting place for a Psalm’ish imagination. Simply take note: taken captive by David’s imagination, a freshly fallen layer of snow becomes a reminder of God’s imputed righteousness: “Wash me, and I shall be whiter than snow” (51:7). Swept up into David’s imagination, a lowly little plant becomes a reminder of God’s cleansing grace: “Purge me with hyssop, and I shall be clean.” Even broken bones, those little white skeletal pieces brimming with nerves, become a metaphor for a broken spirit empowered to worship: “let the bones that you have broken rejoice” (51:8). The Psalmist is displaying what it looks like to have an imagination that loves the Lord: like the characters in Up whose desires for children transform every cloud’s shape in the sky, David looks around at the broken physical matter that surrounds him and sees God’s grace. Everywhere.

And so, mostly I think of Jesus. Seized by Christ’s imagination, the first century’s most ordinary food becomes a metaphor for his divinity: “I am the bread of life” (John 6:48). Even simple food flavoring is converted by Christ: “You are the salt of the earth” (Matthew 5:13). And when the birds of the air rest in Christ’s nest, they become reminders of God’s care for us: “You are of more value than many sparrows” (Matthew 10:31).

We might be tempted to write off the massive square footage of Christ’s imagination to genetics—because he was and is God. But Christ also “grew in wisdom and stature,” and the Psalms were the classroom where much of his growth happened. He belonged to the worshiping community of Israel, and the Psalms were the crown jewel of Israel’s worship service. These 150 Psalms composed their prayerbook, songbook, and order of service. Jesus grew up singing, praying, and chanting these poems. Jesus has a Psalm’ish imagination.

Cultivating a Psalm’ish imagination isn’t hard work.

In fact, it’s not “work” at all. It’s the mercy of God that opens the eyes of the heart so that we can see the beauty of God. It’s mostly just grace and affection: the only two influences on the imagination that are stronger than guilt. In fact, I believe that you have already experienced what I’ve written about in practice.

Maybe you experienced it when you first held your baby, or when you first saw your wife walk down the aisle in her wedding dress, or when you were first slain by a crush in high school. Whoever and whenever it was, the weight of affection on your imagination was commanding: every song reminded you of him. Every movie reminded you of her. Every subject in conversation with your friends reminded you of him. The world around you, the everyday stuff of life that had always been there, suddenly transformed into a theater for her beauty. So it is for the Psalmist and his love for the Lord.

So by grace, through imagination in Christ, may we take our seats in the dazzling theater of God’s glory.

COMMENTS

One response to “The Psalm’ish Imagination”

Leave a Reply

So good – so true -.thank you!!