This is the first of a 3-part series on Bruce Cockburn.

The unproved assumption of [the] very common mountain analogy is that the roads go up, not down; that man makes the roads, not God; that religion is man’s search for God, not God’s search for man.

– Peter Kreeft, Fundamentals of the Faith

Our journey is driven by longing…perhaps the overarching human emotion.

– Bruce Cockburn, Rumours of Glory

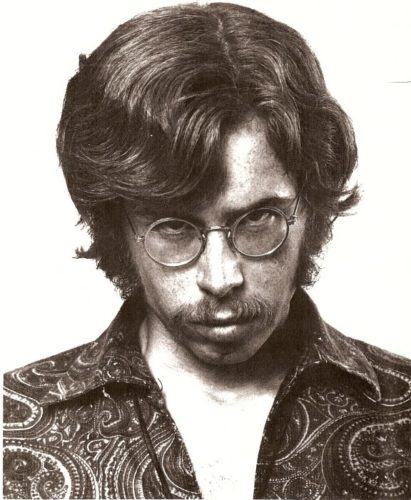

I wonder: how many of you have ever listened to much Bruce Cockburn, eh? Any Canadian readers will at least be familiar with his name. For the rest of you, Cockburn (pronounced Co-burn) is a lefty-Christian-singer-songwriter who gained some acclaim in the U.S. during the 1980s with hits like “Wondering Where the Lions Are”, “If I Had a Rocket Launcher”, and “Lovers in a Dangerous Time”. While his star has since faded outside Canada, he’s continued to put out interesting records and presumably still enjoys pockets of niche popularity in the U.S., not least with a certain Brian-McLaren-reading type of Christian (guilty). In any case, I was surprised to find, with all the great music shared on Mockingbird over the past decade, that a search of its database turned up only one minor reference to any of Cockburn’s work. Perhaps I’m missing something, but that seems to me an unfortunate omission, and one which I hope this (long) career-retrospective post can help to remedy.

I wonder: how many of you have ever listened to much Bruce Cockburn, eh? Any Canadian readers will at least be familiar with his name. For the rest of you, Cockburn (pronounced Co-burn) is a lefty-Christian-singer-songwriter who gained some acclaim in the U.S. during the 1980s with hits like “Wondering Where the Lions Are”, “If I Had a Rocket Launcher”, and “Lovers in a Dangerous Time”. While his star has since faded outside Canada, he’s continued to put out interesting records and presumably still enjoys pockets of niche popularity in the U.S., not least with a certain Brian-McLaren-reading type of Christian (guilty). In any case, I was surprised to find, with all the great music shared on Mockingbird over the past decade, that a search of its database turned up only one minor reference to any of Cockburn’s work. Perhaps I’m missing something, but that seems to me an unfortunate omission, and one which I hope this (long) career-retrospective post can help to remedy.

To many of you, Cockburn’s music will understandably be just a little too earnest at times and politically heavy-handed at others, but for whatever reason, after first being introduced to his music several years ago, I returned to it last fall and have now been on a four-month-long Cockburn binge. What I’ve discovered in the process is that his catalogue of 40+ years has a very interesting narrative arc, one that I think bends God-ward. It’s a story of God’s patient search for a searching patient. Which reminds me of a great Rumi line: “What you seek is seeking you.” Even more than Cockburn’s music, it’s this narrative arc, outlined through song-notes and lyric excerpts from 27 of my favorite Cockburn songs, that I most want to share with you here.

I’ve broken this narrative into these three acts bookended by a “prologue” and “epilogue”:

- Act I: The Joy of Faith (1974-1979)

- Act II: Struggle Against the Darkness of the World (1980-1986)

- Act III: Uncertainty and Spiritual Drift (1987-1999)

While the complexities of Cockburn’s life and music have been massively simplified—and portions of his career, particularly the last two decades, minimized—in the process of fitting them into this “narrative”, each of these acts nevertheless represent clear stages for Cockburn, beginning with his conversion to Christianity in the mid-1970s. He alluded to these stages himself in the notes to a 2002 compilation: “The stuff from the ‘70s was a product of inward-looking exercises, and then it got very much outward directed through the ‘80s, and started to swing back so that you get some of both in the ‘90s, and by the end of the ‘90s, it’s back to internal again, but in what I hope is a deeper way. It’s not my idea that love is at the center of everything, but I believe it is, and I understand a lot more about that than I did in the ‘70s.” It’s this deepening cyclic journey of the spiritual life, driven by what one might call a strange and holy longing, that perhaps you can relate to. If not, I hope you at least enjoy the tunes.

[FYI: My notes draw heavily on commentary from Cockburn himself, most of which is from cockburnproject.net.]

Prologue: The Journey Begins

Bruce Cockburn was born in Ottawa, Ontario in 1945. As a teenager, he became obsessed with rock‘n’roll and took to playing along to Elvis records on a guitar he’d been given by his aunt. After leaving high school, Cockburn spent a few months travelling Europe, “busking on the streets of Paris (and spending a night in jail there for performing without a license) and getting a taste of the bohemian life.” He then returned to North America and enrolled in Boston’s Berklee College of Music, where he lasted a few semesters before returning home to Ottawa (sans degree) in 1965. For the next three years, Cockburn played in a series of modestly successful rock bands in Ottawa and Toronto dabbling in a range of musical styles. After the most successful of these dissolved in 1968, Cockburn decided to pursue a solo career and began songwriting in earnest. About this time, his musical focus also shifted towards a stripped-down folk-acoustic style that would characterize much of his output for the next decade. In 1969, Cockburn married Kitty Macauley, and spent the next few years traveling across Canada in a camper with Kitty and their dog playing shows and building a national following.

Although Cockburn was raised in a largely agnostic household, his first few albums (1970-73) display his deep sense of spiritual connection to the natural world and fascination with spiritual subjects, including aspects of Buddhist teaching and other Eastern religious traditions. But there were also hints of Christian influence: beautifully poetic early songs like “Thoughts on a Rainy Afternoon” (1969) and “God Bless the Children” (1972), for example, incorporate vague Christian language. As Cockburn later wrote, “I wasn’t a Christian yet when I made those records although I was heading (being dragged by the nose might be better) that way.”

1. One Day I Walk (1970)

Oh I have been a beggar

And shall be one again

And few the ones with help to lend

Within the world of men […]I have sat on the street corner

And watched the bootheels shine

And cried out glad and cried out sad

With every voice but mineOne day I walk in flowers

One day I walk on stones

Today I walk in hours

One day I shall be home

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wt9CqKqcyw0

This simple, sweet-sounding first song is from Cockburn’s second studio album, High Winds White Sky (1971). As he later explained, the album represented “a time of reaction — trying to leave behind the years of bad rock bands, trying to clear out psychedelic decadence that was itself a reaction to institutional decadence. Looking for purity in nature. Looking for connections behind things.” It was also a time, as noted, when Cockburn’s lyrics were heavily influenced by Eastern religions. This early search for musical and philosophical purity shines through in “One Day I Walk”, written from the point of view of a wandering street-busker.

To me, it also offers a nice prelude to the journey to come for Cockburn. In particular, lines like “[I] cried out glad and cried out sad / with every voice but mine”, seem to suggest a young man’s self-conscious search for a true(r) self, one which might someday find its rest, or “home” (in God?). It’s also a song—like many of Bob Dylan’s early songs, in this respect—about wandering or drifting. In a 1992 interview, Cockburn noted, “I’m a restless person by nature and I’ve been involved, on and off, with things that don’t go away, really.” This restless longing has remained at the heart of his music for almost five decades since.

Act I: The Joy of Faith (1974-1979)

In the summer of 1974, Cockburn experienced “a kind of conversion [to Christianity]. It was a very long term, slow one, not the light and voice from heaven like St. Paul. But when it finally was over, I had to look at my life and either commit myself to it or pass.” This experience was commemorated in “All the Diamonds”, Cockburn’s first overtly Christian song, and throughout the rest of the 1970s, his songwriting would be pervaded by Christian themes and imagery. As he later described it, “Like anything else that’s new, just like Alcoholics Anonymous or any other kind of thing where you discover some great new thing, you want to go out and tell everybody about it, whether they want to hear it or not… I was a new Christian… So, I was trying to figure out what it meant to be a Christian now that I’d made this move, and the first thing you try to do is, you try to find what all the rules are, and then you try to obey them. That makes you kind of a fundamentalist… But in the end I was completely unsuccessful at being a fundamentalist.”

Despite its religious content, Cockburn’s serene folk music from this period—also rich in nautical and pastoral imagery reflecting his experiences in eastern Canada—continued to endear him to many nonbelievers. As one article cautioned, “to call him a ‘Christian singer’ would be a misleading categorization. Unlike many other Christian musicians, his songs [mostly] veered away from the evangelical and fundamentalist and were almost mystical.” Of course, Cockburn admitted, “I never felt like much of a mystic… [But] I certainly have a sense of the presence of the spiritual in things.” Even in his later career, at times when he’d mostly stopped writing “Christian” songs, this sense “of the spiritual in things” continued to infuse his songwriting.

2. All the Diamonds (1974)

All the diamonds in this world

That mean anything to me

Are conjured up by wind and sunlight

Sparkling on the seaI ran aground in a harbor town

Lost the taste for being free

Thank God He sent some gull-chased ship

To carry me to seaTwo thousand years and half a world away

Dying trees still grow greener when you pray

Written while on a trip to Stockholm, on “the day after I actually took a look at myself and realized that I was a Christian,” this luminous folk song captures the gratitude and beauty Cockburn felt at that immense turning point in his life. The imagery of the moment informs every aspect of the song: “A boat ride through the Stockholm archipelago — barren islands, sun on waves — the balance tipping toward a commitment to Christ. The words seemed to want a church-like music…” Accordingly, he later added, the “style was self-consciously hymn-like.”

3. Festival of Friends (1975)

An elegant song won’t hold up long

When the palace falls and the parlor’s gone

We all must leave but it’s not the end

We’ll meet again at the festival of friends.Smiles and laughter and pleasant times

There’s love in the world but it’s hard to find

I’m so glad I found you — I’d just like to extend

An invitation to the festival of friends.Some of us live and some of us die

Someday God’s going to tell us why

Open your heart and grow with what life sends

That’s your ticket to the festival of friends.

This sweet little tune may be a little too sweet for some, but it was written as a kind of hopeful ode after some of Cockburn’s friends lost a baby to Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. The lyrics illustrate the simple purity of his faith at the time, exemplified in his concept of the Kingdom of God—variously referred by others as the Beloved Community, the Civilization of Love, the Economy of Mercy, the Kin-dom of God—as a “Festival of Friends.” Sounds about right to me.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pnRx2xCiSNc

4. Gavin’s Woodpile (1975)

I remember crackling embers

Colored windows shining through the rain

Like the colored slicks on The English River

Death in the marrow and death in the liver

And some government gambler with his mouth full of steak

Saying, “If you can’t eat the fish, fish in some other lake.

To watch a people die – it is no new thing.”

And the stack of wood grows higher and higher

And a helpless rage seems to set my brain on fire. […]A mist rises as the sun goes down

And the light that’s left forms a kind of crown

The earth is bread, the sun is wine

It’s a sign of a hope that’s ours for all time.

Cockburn wrote only a handful of songs in the 1970s dealing directly with political themes, of which this brooding eight-minute folk rumination is perhaps the best. The excerpt above references the English River, which, as Cockburn explained, was a “river system in north-western Ontario, polluted [by the] Reid paper company. Nobody’s doing much about the fact that the native people who live along its course have lost both food and livelihood, as well as being poisoned because of the contaminated fish.” As he later elaborated: “The song was a gathering of images and emotions focused around what might be called ‘transcendental wood chopping’. The themes are common ones in my stuff, because they are the dominant ones in what I see around me — the failure of human responsibility, our destruction of our natural habitat, a sort of claustrophobia resulting from expanding population, encroachment on the natural world, ever more regulation of one’s personal space — the hope offered by faith.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4GhCwf-iX94

5. Lord of the Starfields (1976)

Lord of the starfields

Sower of life,

Heaven and earth are

Full of your lightVoice of the nova

Smile of the dew

All of our yearning

Only comes home to youO love that fires the sun

Keep me burning

This was the song that actually reignited my interest in Cockburn’s music. I stumbled upon it while searching for language for a prayer I was writing for my church—which makes sense, because Cockburn was trying, in his own words, “to write something like a psalm.” The lines of the chorus themselves—“O love that fires the sun / Keep me burning”—offer a compressed prayer of longing that resonates with me to this day, and reminds me of a few of my favorite testosterone-infused lines from one of Donne’s Holy Sonnets: “Take me to you, imprison me, for I, / Except you enthrall me, never shall be free, / Nor ever chaste, except you ravish me.”

6. Wondering Where the Lions Are (1979)

Sun’s up, uh huh, looks okay

The world survives into another day

And I’m thinking about eternity

Some kind of ecstasy got a hold on meI had another dream about lions at the door

They weren’t half as frightening as they were before

But I’m thinking about eternity

Some kind of ecstasy got a hold on meWalls, windows, trees, waves coming through

You be in me and I’ll be in you

Together in eternity

Some kind of ecstasy got a hold on me […]And I’m wondering where the lions are…

I’m wondering where the lions are…

By the late 1970s, Cockburn had gained acclaim as a folk musician across Canada, but remained largely unknown abroad. That began to change in 1979 with the release of Dancing in the Dragon’s Jaws and this sugary, upbeat pop song, his first international hit. Despite its religious themes, “Wondering Where the Lions Are” reached No. 21 on the Billboard Hot 100 in the U.S., and even garnered Cockburn an appearance on Saturday Night Live.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3k_xkhoq7YM

The song’s lyrics were inspired by a dream Cockburn had had after an ominous conversation with a relative who worked in national security for the Canadian government. As Cockburn explains, “At that time China and the Soviet Union were almost at war on their mutual border. And both of them had nuclear capabilities. I had dinner with this relative of mine and he said, ‘We could wake up tomorrow to a nuclear war.’ Coming from him, it was a serious statement.” That night, “[I had] a rerun of a dream I’d had some years before in which lions roamed the streets in terrifying fashion, only this time they weren’t threatening at all.” In fact, he explains, “it was kind of a peaceful thing.” The next morning, Cockburn woke up to find that, thank God, there was no “nuclear war. It was a real nice day and there was all this good stuff going on…”

7. Rumours of Glory (1979)

Above the dark town

After the sun’s gone down

Two vapour trails cross the sky

Catching the day’s last slow goodbye

Black skyline looks rich as velvet

Something is shining

Like gold but better

Rumours of glorySmiles mixed with curses

The crowd disperses

About whom no details are known

Each one alone yet not alone

Behind the pain/fear

Etched on the faces

Something is shining

Like gold but better

Rumours of glory

This buoyant reggae-styled single from 1980’s Humans was thematically linked to another song from the same album—“Grim Travellers”—which deals with the darker side of human nature. (Unfortunately, the latter song is not as good.) In Cockburn’s words: “There’s often a great beauty for me in the play of opposites. You can’t understand good or be good without an understanding on some level of evil.” He continued:

Based on whatever observations I’ve done of history there’s nothing I’ve seen that indicates people have the ability to straighten themselves out… “Grim Travellers”… [is] about the fact that none of us are free from the darker qualities that are part of human nature in general. It’s a fairly hopeless song. One of the reasons why we followed it with “Rumours of Glory” is that it gives the other side of the coin—that however negative we can be, we… are capable of great love.

As a Louisvillian and Thomas Merton fan, this hopeful song reminds me of Merton’s famous “epiphany” at the corner of 4th and Walnut in downtown Louisville. In his journals, Merton recalled being “suddenly overwhelmed with the realization that I loved all those people… I have the immense joy of being… a member of a race in which God Himself became incarnate… And if only everybody could realize this! But it cannot be explained. There is no way of telling people that they are all walking around shining like the sun.”

Much of Cockburn’s early work echoed this positive spirit. As he later explained, “If you look at what I wrote in the seventies, it’s full of sunlight… There was all this optimism.” And yet, “it was a period when I was searching but very unaware of my own inner workings.” Despite the optimism of songs like “Rumours of Glory” and “Wondering Where the Lions Are”, both from 1979, by the end of the decade Cockburn was indeed in the process of shifting towards a prolonged preoccupation in his work with “the darker qualities” of human nature.

Stay tuned for Parts 2 & 3…

COMMENTS

9 responses to “40 Years in the Wilderness: God’s Search for Bruce Cockburn (in 27 Songs) – Part 1”

Leave a Reply

Lovely start. Can’t wait to see the rest. I’ve seen Bruce about 10 times live and loved every one of them. Thanks.

I am really glad you wrote this for us, Ben. Cockburn’s been a huge blind spot for me, one whose discography is so vast I never knew where to start. Now I do. Thank you! Can’t wait for the next two installments.

I loved this! I’ve always been a big Cockburn fan. My favorite album is High Winds White Sky.

“In the place my wonder comes from, there, I find you…” So wonderful! Thanks for this.

Many, many thanks for bringing Mr. Cockburn to a wider audience. Like Jim, above, he’s been a musical friend and brother since the early 70s, and he’s still making significant music. Keep ’em coming– and shalom!

Cockburn has been my favorite musicians since I accidentally discovered him in 1986 via a demo cassette copy of “Wondering Where the Lions Are” in a bargain bin at a Christian book store. Seems he was too liberal for them! LOL – can’t imagine what they’d say now if that store still existed.

Great article – you’ve captured much about those early works that I love. But what puzzles me is why you’re only planning on 3 parts. His latest release, Bone on Bone, has returned again to Christian themes, and certainly other more recent works reflect his faith and passion for social justice as well. I hope you’ll expand the series!

Just found this today–searching for “songs about suffering” for a Sunday sermon 😉 …And this is GREAT! Thanks so much for this piece. Bruce is probably my favorite singer/songwriter, and I perhaps our greatest living songwriter today. Great work here. Again, thanks so much!