I love Christmas music. I say that fully aware of the considerable aesthetic shortcomings that this love means I must endure, and yet every year as dusk falls upon Thanksgiving Day, I tune in like a character in a Lou Reed song waiting for their man. I find it easy to overlook the saccharine sweetness that under most other circumstances would be a disincentive, to say the absolute least: at no other point in time would I ever even consider sitting through an entire Barry Manilow song. But if it’s “Jingle Bells” with Expose then you bet your duff I’m supplying every car surrounding me with the soundtrack they didn’t realize they were begging for.

I love the frivolity and reverence that saturate every note and tug the listener unburdened by excessive cynicism towards “the wonderful things we remember all through our lives.” As the song says, “It’s that time of year when the world falls in love: every song you hear seems to say, ‘Merry Christmas— may your new year dreams come true.'” Every strain summons to me a place I recall in the ligaments of my genetic make-up: home. I wouldn’t say that I’m transported so much as the scent and sheen of home dissolve into my immediate surroundings, enlarging to encompass every sidewalk I stroll upon and every store I shop at. Home becomes wherever I am as I repose within the quilted chill of yuletide radio.

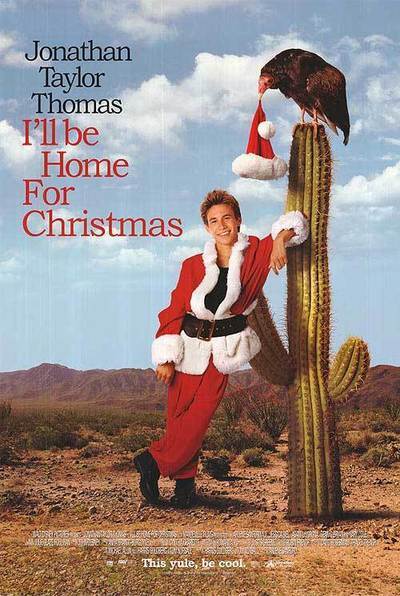

My favorite song in the seasonal repertoire, though, simply has to be “I’ll Be Home For Christmas.” Its unhurried pace and pacific melody quiet my anxieties and hearken me back to hearth and kin, to celebratory meals and joyful gift exchanges. And that halcyon vision is why I’m glad that the songs concludes with the line, “I’ll be home for Christmas, if only in my dreams.” That concessive “if only” ministers to me immensely because the images and feelings the song evokes are speculative for me. What memories I have of that sort are stolen fragments I retroactively inflate to imagine what these songs extol, the things others have been blessed with and perhaps underappreciate.

My parents have been divorced for the vast majority of my life. It is now vastly stranger to imagine them together than it is to survey the ruins we familiarized ourselves with and sequestered ourselves within for twenty eight years now. I won’t bother to catalogue the inventory of their sins against each other and against me and my sister as, in spite of the tension that exists between us (to differing degrees), I love them. And tallying their wrongs would open up a causal web of foolishness and disregard and cruelty that implicates me right along with them. I acted out when I discovered agency enough to aggravate the world and aerosolize my awkwardness and anger when it spilled over capacity and I can see the catechesis I’ve received in all these sad circumstances informing my reflexes even now when I’m under pressure or afraid. Suffice it to say, the gravity of our sinful stupidity would collapse a star. So perhaps it’s a miracle I’m not consumed with bitterness at Christmastime over the un-glamorous goods others routinely enjoy and that I have been deprived of.

I’m thankful to God, then, that the images inscribed within this music silence the fight-or-flight panic that the season and all its expectations and assumed rituals would otherwise incite. One of the wonders of our flesh is its malleability to sound, a perpetual psychosomatic preparedness to recall things completely outside of our experience. It is so open to impression by pitch and timbre and lyric we find ourselves spontaneously, eagerly receptive to tides of emotion that arise from sources not immediate to us apart from those sense impressions. This surplus of meaning creates sensations that are at once painful yet captivatingly beautiful, and they mark out the closeness to God and to one another we were created to enjoy, but have forfeited. The ancestral photo album encoded within the flesh and blood of Adam’s race threads us back to memories we have never had, memories of Eden, of home. These maligned packages of sound can mediate a presence-to that participates in a time and a place that is more simple environment, that is the condition of the possibility of any home at any time. They look backwards and yet, if enjoyed rightly, point forwards, beyond the present, to something else.

I’m thankful to God, then, that the images inscribed within this music silence the fight-or-flight panic that the season and all its expectations and assumed rituals would otherwise incite. One of the wonders of our flesh is its malleability to sound, a perpetual psychosomatic preparedness to recall things completely outside of our experience. It is so open to impression by pitch and timbre and lyric we find ourselves spontaneously, eagerly receptive to tides of emotion that arise from sources not immediate to us apart from those sense impressions. This surplus of meaning creates sensations that are at once painful yet captivatingly beautiful, and they mark out the closeness to God and to one another we were created to enjoy, but have forfeited. The ancestral photo album encoded within the flesh and blood of Adam’s race threads us back to memories we have never had, memories of Eden, of home. These maligned packages of sound can mediate a presence-to that participates in a time and a place that is more simple environment, that is the condition of the possibility of any home at any time. They look backwards and yet, if enjoyed rightly, point forwards, beyond the present, to something else.

Thomas Aquinas, following the Epistle to the Hebrews, observed that Christians are all pilgrims, navigating life and the world on our way to the heavenly city. Our inheritance in Adam is exile from the original home that shapes every longing, conscious and unconscious, we ever feel; every desire that ever drives us, good or bad, refracts its light and echoes its laughter. But our adoption as heirs with Christ supplies us with a new course: rescued from aimless wandering we find ourselves aligned with home once more. But it isn’t a home that we return to: it’s the home we were made for, the newer, better city that consummates the covenant between God and creatures. But there’s still lots of ground to traverse between us and it, and that trek is regularly punctuated by distress and exhaustion. Aquinas, in Summa Theologiae II-II:20-21, helpfully brings into focus how the dangers we face on the way come not only from those distresses but also from their withdrawal.

The twin errors lurking on either side of the pilgrim are despair and presumption. Despair errs in thinking that traction and movement are impossible and that hope is an illusion, whereas presumption errs in thinking that movement is superfluous because the pilgrim has arrived. Hope is unnecessary because the pilgrim has secured everything she needs and has it within arm’s reach. Or so she thinks, anyway. What we need in both scenarios is a glimpse of reality and in Christ both of these pitfalls can be something other than stalls or prison cells: they can deflect and rebound us back to genuine hope. The inevitable disappointment of stuffing too much of the eschaton into the present can goad us into the self-denial that awakens the empty-handed waiting of hope. And the stale inertia of despair can rouse the appetite for the meaningfulness and beauty the soul knows in its marrow is its proper destiny. Hope is situated between the despair and presumption and is the solution to both.

Following this wayfarer theology further up and further in Hebrews brings us to 11:22 where something truly strange occurs: Joseph “remembers” the exodus. You probably won’t recognize it in your English translations (which typically render it as “Joseph made mention of the exodus” or something similar), but make no mistake: the Greek text reads ἐμνημόνευσεν. It’s an aorist active indicative verb, meaning it summarizes a punctiliar event that has been enacted and is now past. It’s the same word John writes in Revelation 18:5 in stating that God has “remembered” Babylon’s crimes and the same word Papias uses when he describes Mark transcribing what the apostle Peter “remembered” in his gospel account.

Following this wayfarer theology further up and further in Hebrews brings us to 11:22 where something truly strange occurs: Joseph “remembers” the exodus. You probably won’t recognize it in your English translations (which typically render it as “Joseph made mention of the exodus” or something similar), but make no mistake: the Greek text reads ἐμνημόνευσεν. It’s an aorist active indicative verb, meaning it summarizes a punctiliar event that has been enacted and is now past. It’s the same word John writes in Revelation 18:5 in stating that God has “remembered” Babylon’s crimes and the same word Papias uses when he describes Mark transcribing what the apostle Peter “remembered” in his gospel account.

How then did Joseph remember something that hadn’t taken place yet? That’s an enormous plank in the argument the author of Hebrews is formulating. Faith sees what hope promises. Hope makes the future so substantial in the present it can be discerned and even grasped. By virtue of the faith that has captured us and set us in motion we are able to spy the spires of that city that all exiles search after. It is the capital of hope but is also the fuel of hope, refreshing our frequently exhausted supplies and spurring us on. The gospel fosters a hope that allows us to see beyond the present into the fulfillment of God’s purposes and that hope nourishes our faith.

The mutual nourishment of hope and faith allows us to see behind the inauspicious present the hysterically glorious future. Whatever disappointment drags us down, whatever failure drains us, hope injects the future into the wounds of right now. And hope is endlessly resilient because it is nothing other than the man Jesus Christ’s unyielding faithfulness to his promises. It’s always freshly available, always renewable, as it is the faithfulness of God in Christ gathering up our pitiful faithfulness and covering it with his own. And that hope becomes so distantly, deliciously visible at times in life, in art, and in dreams that, to modify Rainer Maria Rilke’s words only slightly: in Christ, we live not in dreams but in contemplation of a reality that is the blood-bought future.

Our dreams of home can be more than stinging reminders of what we have lost or the cavity we never remember not feeling depleted, or even what we’ve simply taken for granted and belatedly, nauseatingly realized we had undervalued- they are future memories of the final exodus, the ultimate streaming of the nations into the light of the final advent. So as a matter of fact, I will be home for Christmas. But it’s not so much that you can count on me as you can count on the triune God of grace: “He who promised is faithful.” (Hebrews 10:23) Merry Christmas, y’all.

COMMENTS

One response to “If Only In My Dreams”

Leave a Reply

What a marvelous post. Thank you.

And the irony of ‘I’ll Be Home For Christmas’ is, that it was composed during WWII; I believe in 1944? (I could be wrong.)