An important (if not challenging) definition of courage from existential psychologist Rollo May, brother of writer and addiction counselor, Gerald May. This comes from Rollo’s famous book, The Courage to Create—a title dedicated to Paul Tillich’s The Courage to Be—and this section is a description of what May calls the paradox of courage. Courage, as he sees it, goes far beyond strong wills and resolution. It comes from the French word “coeur” or heart. It means something akin to being “full-hearted,” and therefore is incomplete without its ugly counterpart, fear or doubt. Replace “courage” with “belief,” and you have a pretty spot-on reading of Kierkegaardian faith, too.

A curious paradox characteristic of every kind of courage here confronts us. It is the seeming contradiction that we must be fully committed, but we must also be aware at the same time that we might possibly be wrong. This dialectic relationship between conviction and doubt is characteristic of the highest types of courage, and gives the lie to the simplistic definitions that identify courage with mere growth.

People who claim to be absolutely convinced that their stand is the only right one are dangerous. Such conviction is the essence not only of dogmatism, but of its more destructive cousin, fanaticism. It blocks off the user from learning new truth, and it is a dead giveaway of unconscious doubt. The person then has to double his or her protests in order to quiet not only the opposition but his or her own unconscious doubts as well.

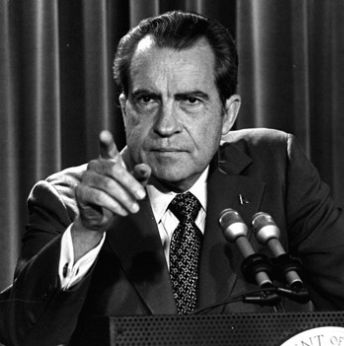

Whenever I heard—as we all did often during the Nixon-Watergate days—the “I am absolutely convinced” tone or the “I want to make this absolutely clear” statement emanating from the White House, I braced myself, for I knew that some dishonesty was being perpetrated by the telltale sign of overemphasis. Shakespeare aptly said, “The lady [or the politician] doth protest too much, methinks.” In such a time, one longs for the presence of a leader like Lincoln, who openly admitted his doubts and as openly preserved his commitment. It is infinitely safer to know that the man at the top has his doubts, as you and I have ours, yet has the courage to move ahead in spite of these doubts. In contrast to the fanatic who has stockaded himself against new truth, the person with the courage to believe and at the same time admit his doubts is flexible and open to new learning.

Paul Cézanne strongly believed that he was discovering and painting a new form of space which would radically influence the future of art, yet he was at the same time filled with painful and ever-present doubts. The relationship between commitment and doubt is by no means an antagonistic one. Commitment is healthiest when it is not without doubt, but in spite of doubt. To believe fully and at the same moment to have doubts is not at all a contradiction: it presupposes a greater respect for truth, an awareness that truth always goes beyond anything that can be said or done at any given moment.

COMMENTS

One response to “Rollo May’s One Paradox of Courage”

Leave a Reply

❤️