Been a while since we’ve talked about this, or heard from this guy. So here you are, a classic DZ technology rant. Throwback!

We were heading in the same direction, an awkward number of steps apart, close enough that we might as well have been walking together. He was maybe ten years older than me, well put-together, kind face and a slightly outdoorsy demeanor. I think I’d seen him around the conference, family in tow, but we hadn’t spoken.

I was about to fall back and let him go ahead when he asked, “You heading to a session?” I was, I replied, the one on technology. It was just up ahead. “Hmm… Not much of technology guy myself – do you know where the Bible one is?” In the building behind us, I ventured.

He stopped and pulled out his phone to check the time–we were both a few minutes late. “You think I need to bring my own Bible? Left mine in the cabin.” I bet they’ll have some, I surmised. “Oh well. I can always use the one in here,” he said, tapping his device, without a trace of irony.

The interaction has been on repeat in my head since we started work on the Technology Issue of the magazine. Regardless of how integral technology has become to our lives, unless we fit a certain demographic (“early adapters”, Silicon Valley, etc), it is still considered a niche interest.

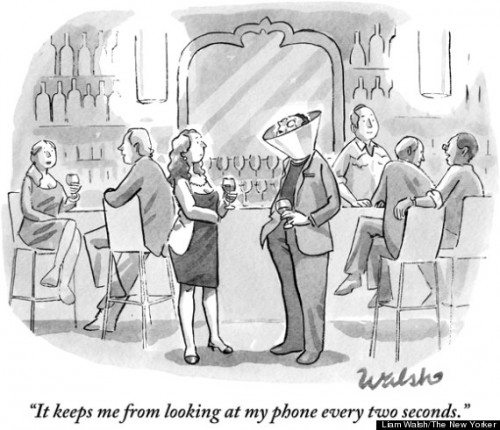

In a talk that very morning, I had dropped my favorite (over-used) line about the gap between who we’d like to be and who we actually are being the same one as exists between our user profiles and our browsing histories. Everyone in the room had nodded their heads, not just the young people. It made immediate sense. We may have yet to integrate technology into our collective self-understanding, but the illustration was the opposite of a stretch.

The experience clarified the challenge (and risk) that lay before us. How do you write about technology in way that appeals to people who don’t want to think of themselves as utterly ensconced in it? Who see it as the purview of other, more mechanically-minded individuals? Moreover, how do you write about technology, even from the perspective of those who owe it a great and ongoing debt, without sounding grumpy or nostalgic or bloodless, overtly utopian or dystopian?

The experience clarified the challenge (and risk) that lay before us. How do you write about technology in way that appeals to people who don’t want to think of themselves as utterly ensconced in it? Who see it as the purview of other, more mechanically-minded individuals? Moreover, how do you write about technology, even from the perspective of those who owe it a great and ongoing debt, without sounding grumpy or nostalgic or bloodless, overtly utopian or dystopian?

I’m still not sure. All I can say is that we gave it our best shot, and I’m super proud of what (some of) you will be reading in a few weeks. We made our case for technology being a topic as central to everyday life (and faith!) as, say, mental health. Not ancillary in the least but of principal interest to those who talk so fondly and frequently about a Mediator (1 Tim 2:5).

How fortuitous it is that we were completing our work the same week that vanguard professor Sherry Turkle released a new book, Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in a Digital Age. Ethan wrote up her editorial that appeared in the Times last week, but Jonathan Franzen’s review of the book merits a post of its own. Franzen, of course, has served as something of a Luddite whipping boy. Yet even as someone deeply invested in the value of digital communication, I can’t help but sympathize with much of his (and her) critique:

[Turkle’s Reclaiming Conversation] is straightforwardly a call to arms: Our rapturous submission to digital technology has led to an atrophying of human capacities like empathy and self-reflection, and the time has come to reassert ourselves, behave like adults and put technology in its place. As in “Alone Together,” Turkle’s argument derives its power from the breadth of her research and the acuity of her psychological insight. The people she interviews have adopted new technologies in pursuit of greater control, only to feel controlled by them. The likably idealized selves that they’ve created with social media leave their real selves all the more isolated. They communicate incessantly but are afraid of face-to-face conversations; they worry, often nostalgically, that they’re missing out on something fundamental.

Conversation presupposes solitude, for example, because it’s in solitude that we learn to think for ourselves and develop a stable sense of self, which is essential for taking other people as they are. (If we’re unable to be separated from our smartphones, Turkle says, we consume other people “in bits and pieces; it is as though we use them as spare parts to support our fragile selves.”)

When you speak to people in person, you’re forced to recognize their full human reality, which is where empathy begins. (A recent study shows a steep decline in empathy, as measured by standard psychological tests, among college students of the smartphone generation.) And conversation carries the risk of boredom, the condition that smartphones have taught us most to fear, which is also the condition in which patience and imagination are developed…

“Reclaiming Conversation” is best appreciated as a sophisticated self-help book. It makes a compelling case that children develop better, students learn better and employees perform better when their mentors set good examples and carve out spaces for face-to-face interactions. Less compelling is Turkle’s call for collective action. She believes that we can and must design technology “that demands that we use it with greater intention.”

That last part is telling. To Franzen, the diagnosis is sound, but the resulting imperatives fall flat, especially to the degree that they ignore the compulsions at work in the first place.

As our relationships with our devices grow steadily more tangled, and the consequences more unavoidable and/or detrimental, books like Turkle’s (and Sven Birkerts’ new one) will appear with greater frequency. Moreover, it will become increasingly apparent what a “proper” or healthy relationship looks like. The through-note, however artfully expressed, will be one of condemnation, guilt, and law. As truthful and well-founded as our techno-gripes may be, they will not be enough to ameliorate the (over-)dependencies or address whatever core fears that are driving the enterprise. They will likely compound them. Our writing about technology therefore cannot be limited to the low anthropology and law which it elucidates so effortlessly. Not when there’s so much ingenuity–and need–on display. After all, there are a lot of really cool things going on.

The law tells us that we must do all we can to develop empathy, that the Great Commandment–to love–is pretty much a non-starter otherwise. And that’s true, as far as it goes. But one wonders if that will ever be enough to get any of us to look up from scanning our screens for the affirmation and distraction we often find there.

The Gospel, on the other hand, speaks a God who does not wait for us to reach out of our own accord but punctures our filter bubbles and mediates boundless empathy for fragile, self-consumed souls. This is the parent who goes further than initiating a conversation with their reticent, well-guarded child, but whose message to that child, even when they don’t respond (or don’t respond empathetically), is one of unabrogated pardon. This is the kind of affection that transcends its mode of delivery.

No wonder we’re still talking–and typing–about it all these years later.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply