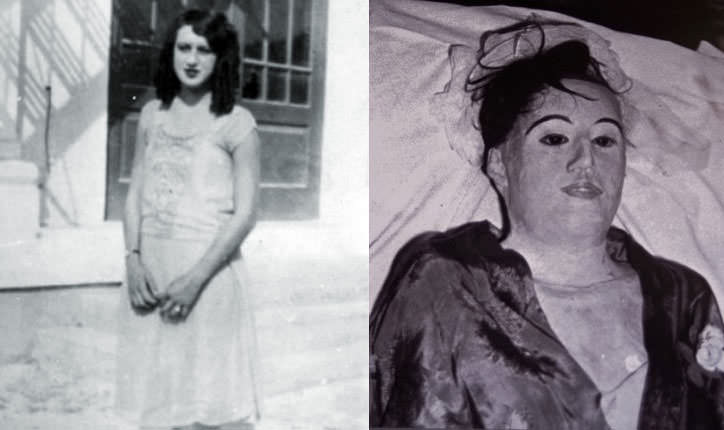

The Miami Herald called it the love story that defied death, the dark romance that hit the front page of the paper in 1940. It all started when Carl Tanzler, or Count Carl von Cosel as he preferred to be called, spotted the beautiful but dying tuberculosis patient Elena Hoyos in a Florida hospital in 1931. Though Elena never returned his affections, was married at the time, and died shortly after she caught von Cosel’s attention, he visited her tomb every day for the next year and half. And then, one fateful night, he claims to have heard Elena singing the lyrics of an old Spanish love song.

“He crumbled the marble on the abandoned tomb, dug the earth, and took the rigid skeleton of his beloved in his arms…”

In a heated moment of what von Cosel later called “inspiration,” he did exactly what the song describes—he dug up the grave, wheeled Elena’s body back home with him in a toy wagon, and preserved her corpse to create the illusion of the beautiful and living woman he had once known. He acted as though this mummified corpse was real for seven long years—dancing with it, spending all his time with it, and practicing necrophilia—until Elena’s sister became suspicious and called the authorities. Von Cosel was arrested on counts of grave robbery, but the charges were soon dropped. By the time The Miami Herald and Key West Citizen wrote about it, the horror story between a delusional old man and his sick patient had evolved into a romance, and the public deeply empathized with von Cosel. At the time of his death a few years later, he was found wrapped around a life size sculpture of Elena that he had created after her mummified corpse had been taken away from him.

Ever since I listened to von Cosel’s story retold by an episode of This American Life, I haven’t been able to stop thinking about this bizarre turn of events. Maybe I just have a liking for macabre story lines since I consider Wuthering Heights and Frankenstein an ideal beach read, but there is so much packed into this story that I have wanted to figure out. And apparently I am not alone, because once I went down the rabbit hole of googling this stranger than fiction story, I found dozens of speculations on von Cosel through in pop culture. Musicians have dedicated songs and even whole albums to their interpretations of him, Ripley’s Believe It or Not Museum in Key West and the Martello Gallery-Key West Art and Historical Museum have exhibits featuring original and recreated parts of Elena, the novel Buried by Tom Baker is a horror story inspired by the true story, and investigative TV shows have examined him. Ronni Thomas, who is working on the newest account of von Cossel in a documentary titled No Place for the Living: the Mad Story of Carl von Cosel, asks whether he was a mad scientist, a hopeless romantic, a corpse reanimater, or something entirely different. But what stands out the most to me, beyond the answers to Von Cosel’s motivations, are the objective facts of this story. The very real sequence of events that include a man digging up a grave in hopes of finding life.

After I spent some cheerful summer months of not pondering over an old man and his corpse bride, Ethan Richardson preached a sermon on the parable of the weeds from Matthew 13. In this parable about separating the good wheat from the bad weeds, Jesus illustrates that as humans, we are unable to distinguish good from bad, right from wrong. Ethan said:

When it comes down to separating wheat from weeds, you are not the man or woman for the job. You cannot solve the world’s problems, you can not even solve your own problems, because you are part of the problem.

This is a difficult parable to swallow for anyone who likes to think they know what’s good for them (which I’m pretty sure is everyone). In a culture bent on self-improvement and self-help, this concept is almost offensive. What does that leave us to do with our internal problems, not to mention our circumstantial ones, that eat away at us—discontentment, anxiety, depression, loneliness, anger, the list goes on. Our deficiencies leave us with gaping holes and to do nothing about it feels maddening. And while not many people have resorted to digging up a deceased lover in their darkest moment, I can at least speak for myself in saying that I have surely gone to dead places in hopes of finding life. Even though the list of speculations revolving around von Cosel could lead to a number of answers, I am sure that with every chink of his shovel, he thought he was one step closer to life. One step closer to filling a gnawing sense of emptiness, or finding the answer to whatever it was that brought him to the grave of a dead woman every day for a year and a half. And I couldn’t help but think about all of this again while listening to Ethan’s sermon; about how many times I have thought I knew exactly what I needed to fix that problem or fill that emptiness. How many graves have I tried to dig up only to find more death at the bottom?

The dictionary defines “inspiration” as an adjective meaning “aroused, animated, or imbued with the spirit to do something, by or as if by supernatural or divine influence.” Feeling inspired is so often correlated to the moments we find life, to the moments where we see the bright light in the wells of emptiness inside of us. People, ideas, art, history, geography—there’s no limit to what inspires people. But the truth is that the things that make us feel “hot hearted” won’t satisfy or fill us. In our humanity, the only inspiration that will lead us to life is the Holy Spirit. So while we want to desperately take a shovel to follow our passions that seem to promise life at the other end, the hard work that the gospel calls us to is rest. The type of rest that causes us to be led by another who will lead us to where life can really be found.

Perhaps the Sufi poet Hafiz said it best:

“Just sit there right now, don’t do a thing.

Just rest.

For your separation from God is the hardest work in this world.”

COMMENTS

One response to “Digging up Death: The Macabre Story of Count Carl von Cosel (And Us)”

Leave a Reply

Amen. I also wonder if these inspirations are the Spirits alien work of bringing us to the end of ourselves (death), so that we would actually (and painfully) realize true rest is only found through Christ, when we are at peace with God, ourselves and others “as is.”