When life gets tough, I like to watch other people’s lives get tougher. In Germany or Avenue Q, this is called shadenfreude; in America, this is called haphazardly engaging in political discourse on social media, or watching just about any popular TV drama. Forgoing the Covfefe hoo-ha, I recently committed instead to a teen soap opera — a precious genre rife with death and tragedy and youth pregnancy scares.

Several episodes deep into a show like Party of Five (1994-2000) and my day-to-day seems pretty alright. The walls begin to lean blessedly outward instead of in. I can breathe, and I kind of make sense to myself again.

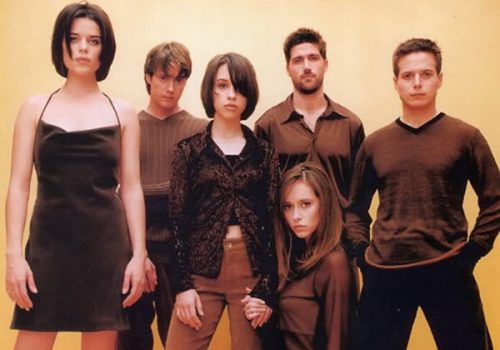

Party of Five (re-released on Netflix this year) follows the five Salinger siblings as they cope with life following the sudden death of their parents. Where the show starts, the oldest sibling, Charlie (played by Matthew Fox of Lost), resists and runs from his new role as guardian.

Hmmm…“resists and runs” from parenthood. Sounds familiar. I might know a guy.

At 24, Charlie had been deep into 20-something life, bar-hopping, bed-hopping, and job-hopping. He was doing what many kids do right out of college — trying to find his own way. But after the death of his parents, who were killed by a drunk driver, Charlie is slowly forced into a way not of his own choosing: parenting his four younger siblings (the youngest of whom is an infant).

Some people like to escape into stories that are exotic and foreign to their lives. In this early-parenting phase of life, I like to ugly-cry into the mirror.

Odd as it seems, Charlie Salinger is the most accurate portrayal of identity-loss in parenthood I may have ever seen.

I very unintentionally came down with my first pregnancy at just several weeks married. And I don’t mean to compare carelessness between the sheets to a tragic death, but lately I’ve succumbed to this feeling that motherhood is something that happened to me — like a planter’s wart or a rogue splatter of bird poo — as opposed to this cherished role I was made to fill. In a small way, parenthood has indeed involved a death: a death to myself. The grief comes and goes.

Most days, I see my children as this perfect, hilarious gift I never asked for. Most days, our lives seem like this magical adventure-story I never would have written for myself. But in the tight spaces between that very real gratitude, sometimes lurking underneath it, threatening to undo it altogether, is the very real longing for my freedom.

I miss doing little things like staying up late or, at the absurd hour of 6pm, deciding to go out for dinner. I miss seeing movies in theaters, perusing the grocery store alone and at the time of my choosing, adults-only weekend trips (without paying a babysitter, or wasting time scrolling through pictures of my kids because I’M HOMESICK FOR THOSE JOKERS). These things seem small. But in the terrible grips of identity-grief, they feel catastrophic. Not to mention the king’s ransom of lost things like dreams and time — time to work, to write, to foster adult friendships, to fill roles that come to me so much more effortlessly.

I wrestle, I give in, and then I wrestle some more.

I am blocked at this juncture of who I feel I was created to be, versus who I actually am: parent.

In the build-up of the first episode of Party of Five, Charlie has refused to move out of his own apartment and back into the house with his siblings. He loses a huge chunk of the family’s money, and relinquishes the responsibility of parenting to the kids themselves.

Bold. And I’ve considered it.

With Charlie, the family must suffer his inner-struggles and his many and unpleasant shortcomings. But without him, they cannot get by at all. They’ll either be taken by social services, or fall apart completely. They need him. By the end of the episode, Charlie seems to finally realize this. He moves home and painfully puts aside his pursuit of a career in woodworking, choosing instead to provide for his family in the immediate. He takes a bartending job at his late-father’s restaurant.

I’m going to do what I should have been doing all along. I’m gonna spend a lot more time here, I’m gonna take more responsibility. I’m gonna look after you guys.

Some days, parenthood (a lot like marriage) really is that matter-of-fact. It’s either/or. It is the impossible decision, only born of grace and caffeine, to say no to yourself and yes to somebody else.

Charlie screws up constantly in his role as parent. He tries and fails in equal measure. If you’ve seen the show’s opening credits, you’ll notice the baby drinking actual fruit punch out of his baby bottle (I know, clutch your pearls). Charlie struggles to pour out to his family and also build up a life for himself. He wrestles and he wrestles with this new, hard story he’s been written into, and I’m with him every weary step of the way.

He says to his siblings:

It’s like what’s yours is yours, and what’s mine is yours.

Whoa.

I don’t have anything that’s just mine. Not the money that I make, not the right to take a job…Everything’s a fight. Nothing is easy. You won’t let me make decisions. You won’t let me make the rules. You won’t even let me make mistakes. I can’t keep doing this and know that you don’t even appreciate it. You don’t even respect me…and then I get angry, and I do things that I don’t mean to do. And that really scares me. I mean, that makes me think I’ve gotta get away. And not just for a four-day weekend or a week, I mean really away…I can’t breathe here anymore.

When my kids are in some blessed [terrifying] developmental stage and needing me to be patient, to pull through for them, needing me to drop my own mess to pick up theirs, I start backpedaling toward the exit. I don’t even realize it’s happening. When my beautiful babies are constantly the source of my “No” — no to friends, to trips, to activities, to jobs — I start having these sad, grievous Charlie-thoughts: “What’s yours is yours and what’s mine is yours,” I think pitifully to myself. “I can’t breathe anymore.”

There is no escape from all this being needed. And what I have to give is not enough.

In the depths of self-victimizing, I cannot imagine why God actually chose to be our father. Why not our BFF or bro? Unlike Charlie, unlike me, God actually wrote us into his story. He cast himself as ‘Parent’ and went to unbelievable extremes to adopt us into his family.

Even stranger is this thought: the exhaustive ways our children relate to us as parents are actually how God longs for us to relate to him. He wants us to need him like a helpless child. My kids need me for absolutely everything. They talk at me non-stop, asking one weird and nonsensical question after another. I am the first person they want in the morning and the last person they want when they go to sleep. My kids depend on me to feed them, to clothe them, to bathe them, and to rescue them over and over and over again. This need is overwhelming because I am not God. Any day now, they’ll realize this.

In the steep dip of pouring out to my children, I often fail to remember that God — my father — is eager to pour in to me and my own ridiculous and selfish needs as a parent. He fills this awful vacuum. He opens these walls that are so bent on closing in. He puts a smile on my face (and most of the time makes it genuine). He gives me this new identity. Beyond just parent (and whatever I was before parent), I am first and foremost daughter.

The success of God’s parenting was dependent on the death of Jesus. So why did I think my experience of parenthood could escape a death of its own? Thankfully, the story of the gospel is not only one of death, but of redemption and new life. In Jesus, God the father says, ears attentive, arms open wide, and with a heart full of gladness: “Dear one, what’s yours is yours, and what’s mine is yours.”

COMMENTS

3 responses to “Party of Five and the God of Party Poopers”

Leave a Reply

Love this!

Ok, I can’t help but comment on this. I JUST started re-watching this series a month or so ago (it was on FreeForm before it came to Netflix) and you’ve nailed it. I remember watching it in the 90s and being impressed by the quality of the show. Honestly, re-watching, it has only gotten better. And now my perspective is totally changed.

Sure, there is a ton of agenda being pushed by the producers, but in terms of an honest portrayal of real struggles, and real grief, and real pain, I don’t know that anything captures it better. For a show without parents, it’s amazing how often it speaks to parents. And as I’ve told some of my teens (that I have watching the show), if you want to know what many of the homes and experiences of the kids in school around you are like, this will help.

But as with anything, it’s not just “them out there” that can identify and need the gospel, it’s “us in here” that need it as well. Thank you guys for always being so good at presenting that truth!

I loved this show so much when it came out, when I was single and had no children. This makes me want to rewatch it now from the perspective of the parent…!