When it comes to writing about DC Comics’ theological inclinations, there’s no one better for the job than Jeremiah Lawson, aka Wenatchee the Hatchet. Very grateful for his take on the new Wonder Woman:

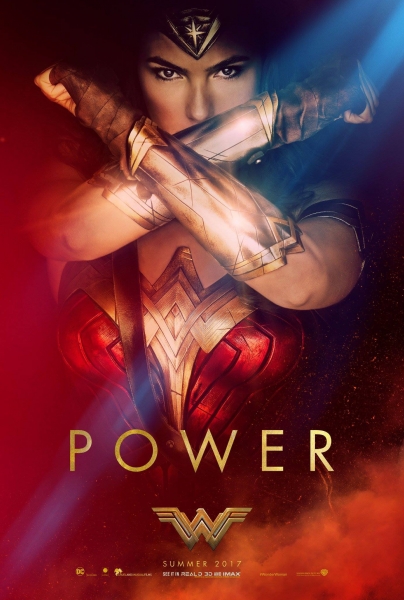

The new Wonder Woman movie is upon us, and the overall reception has been very positive. This is not just because, compared to Man of Steel or Batman vs Superman (let alone Suicide Squad), Patty Jenkins and company have given us a straightforward, charming superhero story where our heroine gets to be heroic; it’s also because you can go watch this Wonder Woman movie and never have to waste any of your time watching the rest of the DC cinematic franchise, if you don’t want to.

The new Wonder Woman movie is upon us, and the overall reception has been very positive. This is not just because, compared to Man of Steel or Batman vs Superman (let alone Suicide Squad), Patty Jenkins and company have given us a straightforward, charming superhero story where our heroine gets to be heroic; it’s also because you can go watch this Wonder Woman movie and never have to waste any of your time watching the rest of the DC cinematic franchise, if you don’t want to.

By now there’s not much need to add more to the chorus of voices praising Gal Gadot’s star-making turn as Diana of Themiscyra (Wonder Woman), or Chris Pine’s charming, affable take on Steve Trevor. Even as someone who hated Batman vs Superman for all kinds of reasons, I was sold on Gadot as Wonder Woman.

As with any film, of course, there are notes of dissent. The most good-natured and playful note of dissent comes from Noah Berlatsky, over at The Verge, who misses Wonder Woman’s use of space kangaroos (which, seriously, are in the comics). Other reviewers have expressed disappointment that once the “appealing misandry” of the Amazonian culture has been left behind, the movie becomes dull and full of mansplaining. We’ll have to return to the question of whether the alleged Amazonian misandry is contempt for males or contempt for humans in general later.

The New Yorker’s Jill Lepore has written that the film has an uninteresting plot involving World War I and that the real fights women waged a century ago get erased:

… the film renders invisible—erases—the fights women waged a century ago for representation, contraception, and equality. The real women who fought them called themselves Amazons, figures from myth, because, not knowing much about the history of women, they had to imagine ancestors. Wonder Woman is their daughter. They made her out of clay. She owes them a debt that this movie does not pay.

Possibly, but, firstly, how could a fictional character ever repay that sort of debt, if it were possible for a superhero movie to owe such a debt?

Secondly, in the 2017 film, there’s a moment where Diana is trying on an outfit and asks how a woman could fight in such a frilly dress. Steve Trevor’s secretary Etta Candy wryly tells Diana that “we fight with our principles,” adding that this would be how women would get the vote. It isn’t exactly a “big” moment, but it’s difficult to see it as rendering suffragettes “invisible,” let alone “erasing” them.

Lepore’s comment about the new Wonder Woman film and its alleged “erasure” reminded me of something I’ve written before: how one of the great difficulties of adapting Wonder Woman into a cinematic narrative is the sheer weight of fan expectation. There are fans of Wonder Woman, and there are fans who took Marston’s claim that she was propaganda to give people a vision of the sort of women who should run the world so seriously that anything less than that realization in film falls short; until recently, Wonder Woman may have had to mean too many things to too few people. Patty Jenkins and Gal Gadot may have done for Wonder Woman what Richard Donner and Christopher Reeve once did for Superman, but there are those for whom this will not suffice.

For others, there are other problems. At The New Republic, Josephine Livingstone has seen Jenkins’ film as propaganda for the ideology of American exceptionalism:

The engine of American ideology drives Wonder Woman, which is in the end a movie about violence. It is also a surreal movie, because of the way it draws upon the world’s past to make a distinctly American fiction. … This movie is a document of political indoctrination. It’s great to watch a hot woman punch through walls. It was also a privilege to witness giantess-fetishes flower in so many young minds at the same time. But the idea that we should debate how “feminist” Wonder Woman may or may not be is, despite its female director and star, laughable.

Here, too, this criticism of the Wonder Woman film highlights the several problems I’ve mentioned in Marston’s original Wonder Woman story. The three fatal flaws I described in Marston’s story for any contemporary adaptation were as follows:

1) his utopian gender essentialism about women in 1941 can’t be squared with women in political power (spanning the political and ideological spectrum from Madame Mao to Margaret Thatcher) that have shown us there’s no reason to believe women are much different from men when it comes to wielding political and social power

2) Marston’s American exceptionalism was jingoistic to a degree that does not quite settle with subsequent feminist criticism of the post-war American mainstream culture, to say nothing of its history regarding race

3) Marston’s idiosyncratic take on Greco-Roman gods can’t be squared with just about anything we could read about them from Greek mythology itself. Not coincidentally, even this year’s Wonder Woman film features a drastically revised Greek pantheon but we’ll get to this, too, later.

A fourth difficulty is that Marston’s original origin for Wonder Woman shows us she was a golem. None of these problems are insuperable but they have all been problems in the original 20th century origin for the character that have to be addressed to update her story for the 21st century. Patty Jenkins’ film manages to address these.

Now the animated series Justice League also managed to address and solve the problems inherent in Marston’s origin story. I’ve written at some length about that elsewhere. The new movie largely solves the problems of Marston’s origin story but in significantly different ways. Diana is told a story by her mother Hippolyta of how Zeus created the Amazons. When Zeus had finished making the other gods, he made humans. Among the gods, Zeus’ son, Ares, resented that Zeus made humanity; Zeus made humanity in his image and gave them blessings that Ares envied, so Ares set out to show how corruptible humanity was and inspired them to ambition, greed, envy, and war. Thus Ares, the traditional god of war, has become John Milton’s Lucifer from Paradise Lost.

In one fell swoop the gender essentialism and the off-kilter take on the Greco-Roman pantheon have been changed. No longer are humans the creation of a Prometheus and Athena, no longer is Promethus punished for making humans from the earth and favoring them with knowledge and with fire. Instead it is Zeus who makes humanity and envious Ares who sets out to prove they are not worthy of even life itself. Along the way, however, Ares kills all the other gods but Zeus. In the end Zeus himself dies but not before creating the Amazons and giving them the god-killer, a weapon destined to defeat Ares and make the world safer for humanity. No longer are the Amazons a group of women given immortality and wisdom by Aphrodite after their queen Hippolyta was seduced by Ares into giving him a golden girdle granting invincibility in battle.

But as with many stories children hear from parents, this story turns out to be partly true. As Gal Gadot’s Diana accompanies the American spy Steve Trevor to London to search for and ultimately kill Ares to end the War to End All Wars, she discovers that Ares is harder to find than she thought. She is sure that Ares has taken the form of German general Erich Ludendorff, a historical figure from World War I. Ludendorff, in this film, has employed the chemical weapons specialist Dr. Maru (aka Doctor Poison, played by Elena Anaya) to develop a new and even more virulent form of mustard gas that uses hydrogen rather than sulfur. This fantasy weapon couldn’t actually work, so we’re still firmly in superhero science (i.e. magic). That said, World War I was a war in which the horrors of chemical warfare exploded onto our planet with ghastly consequences.

In the film Ludendorff’s plot is to unleash the weapon on those political figures who would sign what would become the Treaty of Versailles. Steve Trevor and Diana set out to stop Ludendorff and Doctor Poison but cannot muster support from Parliament in England. They are secretly dispatched by an English lord to go kill Ludendorff and Doctor Poison so, as the English lord puts it, the armistice can be completed. Without any official blessing Steve Trevor and Diana recruit a band of motley scoundrels. Diana is dubious as to whether this small band of liars, killers, thieves, and smugglers make for honorable warriors. Trevor, ever the spy, replies that he is, in fact, a liar, a killer, a thief, and a smuggler and asks Diana if she still wants to go with him to the front to find Ares. By this point Diana has heard from Steve the tale of how his father told him that if there’s something wrong with the world you can either do nothing or do something, and how Steve said he’d already tried nothing. What Diana gets to observe in Trevor is that, even when you want to do good in the world of men, you can’t avoid getting your hands dirty.

If that’s the best the world of men can do, what is the worst they can do? Along her way to No Man’s Land Diana talks with Trevor’s mercenaries, one of them a Native American nicknamed the Chief. The Chief tells her he’s been far from his homeland in America because his people were killed. Diana asks the Chief who killed his people and the Chief motions to Steve Trevor and says, “His people.” While this motley crew of stock characters has largely been skimmed over by reviewers, their stories are not simply filler. These men share with Diana that they wanted other things from life but racial injustice and racial violence have left them adrift, and in being adrift they have taken up dirty work of the sort where they could be recruited by a spy like Steve Trevor. Diana gets to see and hear for herself what her mother Hippolyta meant when she said the world of men did not deserve her help.

The Amazons, Diana discovers at length, have no particular interest in saving the world of men. They hold mortal men and women alike in contempt. The Amazons are not for humanity; they are merely against Ares. As she departs for the world of men, Diana is warned by her mother: “If you leave, you may never return.” Diana’s response is to ask, “Who would I be if I stayed?” Diana is not just angry that Ares has sown death and war across the world in humanity but that her adoptive people, the Amazons, regard that verdict of death as justly deserved. But seeing the violence and deceit that even seemingly good men like Steve Trevor are willing to perpetrate for what they believe to be good causes, such as ending war, Diana begins to wonder whether her mother was right. Perhaps humanity does not deserve her aid, after all. Seeing the ghastly results of Doctor Poison’s chemical weapons shows Diana that men and women alike are capable of horrifying evil.

By the final act Diana confronts and defeats General Ludendorff, but even after she runs him through with her sword nothing changes. Steve proposes to Diana a question: “What if there is no Ares?” What if humanity doesn’t even need an Ares, a god of war, to war with itself? Diana says that her mother was right, that the world of men did not deserve her help. Steve tells her that it’s not about whether or not humanity deserves her help but about what she believes, if she believes that humans are worth saving. He can help formally end the war if she can help him stop Doctor Poison’s weapon from being used against those leaders who would work toward peace.

Up to this point every god, demigod, or Amazon available to offer an opinion has told Diana that humans, men and women alike, aren’t worth saving. Perhaps ironically, though the Amazons are presented in this film as devoted and sworn enemies of Ares created by Zeus, in traditional Greek mythology the Amazons were regarded as daughters of Ares who venerated him.

At length Ares finally reveals himself to be the English lord who sent Steve Trevor and Diana to go kill Ludendorff. Ares reveals that all he has done is inspire men and women to the discipline and innovation they needed to accomplish great things. He didn’t tell them to do anything as evil as what they have done, they have done these evil things of their own accord. Ares has been reconceived not as the god of brute force, bloodlust, and courage on the battlefield but as the tempter, manipulator, and deceiver; in short, this is far less a Hellenistic Ares than a Miltonian Lucifer. What remains of a Hellenistic myth is that Ares reveals that in giving the Amazons the legendary “god killer,” Zeus gave them Diana, because “Only a god can kill a god.” Ares tells Diana that the world was beautiful and rich before humans corrupted and polluted it, that if she would join him and wipe humanity off the face of the earth, it could become the gorgeous paradise for the gods that it once was before Zeus created humanity. Ares takes Doctor Poison as the exemplar of the cruelty and sadism of humanity, its treachery, its egotism, its vanity. He urges Diana to begin wiping out the humanity that is unworthy of her or any other immortal so that the gods alone can enjoy the earth.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D1fOJ8sghp4

Diana replies, “Everything you say about them is true, but they are so much more than that.” Though in Greek mythology Zeus looked at humans, a creation of Promethus, with contempt, in this cinematic narrative humanity is fashioned in Zeus’ image. In the final conflict between Diana and Ares the question at stake is not really whether one holds to a “high anthropology” or a “low anthropology,” because both Diana and Ares can see just how venal and cruel humanity has been. The conflict is about the question of whether or not this low anthropology can be construed as a “floor” or a “ceiling.” Ares views the worst that humanity is as the best they can be and he, like the Amazons who raised Diana, regards the entire human race as unworthy of life. Best to just destroy them and reserve the world for worthier forms of life. Diana sees the baseness of the human condition in a way that can be described as a floor. There may be unusually depraved individuals but on the whole humanity is, as it were, bound by the gravity of weakness to the floor. They cannot jump, step, or fly above the floor their feet stand on if no one helps them. Though she discovers she cannot make men or women choose good over evil, she can help them fight for the good when they choose it. If the choice has to be between gods and demigods who would see humanity wiped out and saving humanity from the cruelty of self-aggrandizing gods and demigods, Diana chooses to help humanity even though she has seen why her mother said of humanity, “They do not deserve you.”

Diana defeats and kills Ares in battle and then lives through a whole century observing the bloodshed and cruelty of humanity. She gets to see that the violence Ares has sown in humanity leads the War to End All Wars to be nothing more than a prelude to another, greater war. Though Diana was able to see in Steve Trevor and his band of mercenaries a desire to live a better, purer life, these were men trapped by their own frailties and the injustices of the world they were born into. She has seen, too, that none of her powers can be used to bring back the untold lives taken by the chemical weapons of Doctor Poison. Diana crushes the Ares who played the tempter but to no avail; humanity, obviously, stuck to the business of war. As heroic as Diana is and aspires to be, in the end she discovers that she was born to be the god killer, the one who kills Ares. What her mother Hippolyta was trying to keep her from was realizing this moment of destiny.

Yet even after Diana fulfills the role of the Amazons and defeats the god of war, humanity goes on waging war, and Diana, it seems, has been effectively banished for choosing to believe humanity was worth saving. As a child, she aspired to use the god killer to make the world a better, safer place; as a woman, she finds that being the god killer cannot really make the world a better, safer place. Diana may be able to save humanity from their would-be destroyer but she can’t redeem them from bondage to their own vices. It’s hardly the case that being a moral example counts for nothing, but we know from plenty of theological reflections over millennia that if merely having enough good (or good enough) moral examples were sufficient, no humans would have ever imagined that humanity needed such a thing as salvation.

COMMENTS

3 responses to “Defeat Even in Victory: Wonder Woman, Critical Response, and Modes of Low Anthropology”

Leave a Reply

Thanks for putting into words in a great article what I was thinking after I saw this yesterday. I imagined an article on Mockingbird with something like “Wonder Woman AKA How Princess Diana Learned to Live with a Low Anthropology” and I check the site today and your article comes up! All critiques of the film from critics about how the movie should be more patriarchy smashing aside (I mean, she’s literally smashing things, helping win the war, is given a fantastic character arc, and saving humanity – what more do you want?) I came away from the film grateful that scripture and theology have given me the Saint/Sinner understanding that is hinted in at the film but can never take its full and most powerful form without Jesus, the cross, death, and resurrection.

I find it funny that even pre-Nazis, the Germans are the go-to villain. I guess if Captain America beat Wonder Woman to the punch, otherwise they might have gone with that as a setting for her origin story. I guess having some rando knighted Englishmen is better than nothing, but imagine if the plot was that Churchill was Ares and Diana carved up Anglo regiments? As if Britain wasn’t a much larger and more brutal empire?

cal, i wondered the same thing when i saw it — and jeremiah touches on this above. what an odd mission, to save the treaty of versailles — not quite futile, but not quite ‘heroic’ either, given that history is slowly coming to accept what a nightmare that treaty was, especially for what is now ‘the middle east.’

thanks for this, jeremiah. a great take on what was obviously a very religious movie