Lots of love – commingled with envy – for everyone at the Tenth Annual Mockingbird Conference in NYC! “For the rest of us” (G. Costanza), some links for the weekend:

1. First up, The Hedgehog Review here in c-ville posted a wonderful article on “The Persistence of Guilt.” Who knew that the great Sigmund Freud once quipped, “the price we pay for our advance in civilization is a loss of happiness through the heightening of the sense of guilt”? The author argues that Freud helped “demoralize” guilt, to suggest that our guilty emotions were the product of the superego and could be safely bracketed away, ‘out there’, as a sort of contingent product of some process which the psychotherapist could demystify. According to the author, “Health was the only remaining criterion for success or failure in therapy, and health was a functional category, not an ontological one.” Whether or not it’s a good reading of Freud, it certainly describes where we are now. That is, since guilt is just another negative emotion, we can handle it the same way we handle other bad feelings – just “shake it off” (T. Swift).

Strangely, however, we have more to feel guilty about now than ever before. As McClay writes for The Hedgehog,

I can see pictures of a starving child in a remote corner of the world on my television, and know for a fact that I could travel to that faraway place and relieve that child’s immediate suffering, if I cared to. I don’t do it, but I know I could. Although if I did so, I would be a well-meaning fool like Dickens’s ludicrous Mrs. Jellyby, who grossly neglects her own family and neighborhood in favor of the distant philanthropy of African missions. Either way, some measure of guilt would seem to be my inescapable lot, as an empowered man living in an interconnected world.

Whatever donation I make to a charitable organization, it can never be as much as I could have given. I can never diminish my carbon footprint enough, or give to the poor enough, or support medical research enough, or otherwise do the things that would render me morally blameless. . .

Guilt, of the silly and serious varieties, resurges. Examples are endless. We’ve partially deconstructed the damaging, artificial Law of Personal Beauty, but are more obsessed with quinoa and three-digit gym memberships than ever before. We’ve made strides toward racial justice, but found the persisting effects of past sins to be limitless. We pushed away the college sex police in the seventies, removing university oversight, affirming sex and alcohol, and going to coed dorms, and were somehow surprised when the old moral revulsions (and attendant policing) came back in different forms. What remains of a feel-good culture’s promise that you can just make all this go away? Distraction’s always an option. But the actual way in which elites (in particular) have dealt with this guilt may be more metaphysical:

Making a claim to the status of certified victim, or identifying with victims, however, offers itself as a substitute means by which the moral burden of sin can be shifted, and one’s innocence affirmed. Recognition of this substitution may operate with particular strength in certain individuals, such as De Wael and her fellow hoaxing memoirists. But the strangeness of the phenomenon suggests a larger shift of sensibility, which represents a change in the moral economy of sin. And almost none of it has occurred consciously. It is not something as simple as hypocrisy that we are seeing. Instead, it is a story of people working out their salvation in fear and trembling. . .

In the modern West, the moral economy of sin remains strongly tied to the Judeo-Christian tradition, and the fundamental truth about sin in the Judeo-Christian tradition is that sin must be paid for or its burden otherwise discharged. It can neither be dissolved by divine fiat nor repressed nor borne forever. . .

(Cue Rene Girard.) It’s a blistering diagnosis, of a mounting guilt which we have no way to expiate. And as Mr. Freud himself noted, that which is repressed tends to return. Without religion, the options for dealing with it are limited. One can take that guilt upon oneself, and despair, or one can foist it onto someone else and crusade against it, giving no quarter. And at least since the Jewish minorities in Europe were blamed for the Black Plague, we (humanity) have tended to choose the latter.

2. A good week on the technology front. Alan Jacobs provides some reflections on how our idolatry now may be different from Calvin’s time. He compared the heart to an idol factory, but back then that means something like a cottage industry, and options for things to idolize were limited. Now, we’ve got computers and cell-phones which can provide us with an infinite array of things to venerate, with an interesting shift:

But when we have access to what I have called “the universal idol-fabricating device,” then each particular idol becomes temporary, dispensable — it is the fabrica itself, the forge or workshop, that becomes the true object of our veneration. The idol-maker has become the idol.

(For those who share a penchant for reading people like Milbank and Charles Taylor and lodging abstract gripes against modernity, we might say that this represents an example of our culture’s shift to valuing process over substance. That is, we might choose something else over God – say, career – but in the contemporary world, our deeper problem is a fetishization of the simple, pluripotent ability to choose in itself, to not be pinned down to any one thing in particular. So it is no longer even a discrete idol, but rather the process of generating idols, which we venerate.)

There’s an app for treating addiction now, which seems like either a mildly good idea or a very bad one. And an app for tracking one’s prejudices (joking, but certainly not unthinkable).

3. Also in tech, The Economist’s 1843, which still seems like it’s finding its feet, had a good article on who we are online. A couple highlights:

Being observed makes us aware of our audience; performing for more people tends to make us exaggerate; time to reflect allows us to self-edit. Perhaps it’s not that Facebook and its ilk are turning us into narcissists, but that they encourage us to broadcast, and broadcasts tend to be narcissistic.

These new platforms have unwrapped latent elements in human nature that have till now remained dormant. Sometimes these emerging identities are beautiful. Extreme introverts, or people with social anxiety, may shine with articulate brilliance behind a phone or computer. Having a little time and solitude to consider their ideas helps them communicate more effectively.

Social media have turned a species used to intimacy into performers. But these performances are not necessarily false. Personality is who we are in front of other people. The internet, which exposes our elastic personalities to larger and more diverse groups of people, reveals the upper and lower bounds of our capacity for empathy and cruelty, anxiety and confidence.

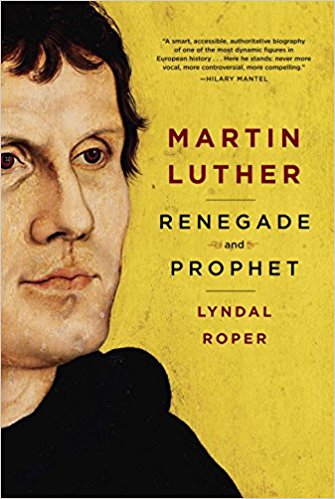

4. The Five Hundredth Anniversary of the Reformation marches on. We hope to eventually review Lyndal Roper’s new biography of Martin Luther, but for now, the New York Times review has us excited. Looking ahead, however, it’s only thirty-seven years until we reach the millennial of the Great Schism! And on that front, The New Yorker wrote an excellent profile of our Orthodox friend Rod Dreher. It takes him quite seriously and honestly while also being sympathetic, and it’s well-worth a read.[1]

4. The Five Hundredth Anniversary of the Reformation marches on. We hope to eventually review Lyndal Roper’s new biography of Martin Luther, but for now, the New York Times review has us excited. Looking ahead, however, it’s only thirty-seven years until we reach the millennial of the Great Schism! And on that front, The New Yorker wrote an excellent profile of our Orthodox friend Rod Dreher. It takes him quite seriously and honestly while also being sympathetic, and it’s well-worth a read.[1]

5. If anyone wants extra motivation to take Dreher’s Benedict Option (Christian reclusion), transhumanism seems like a decent bet. Defining the word isn’t always straightforward, but basically it’s the drive to use technology to thwart familiar human limitations, such as our need to sleep each night (depriving us of eight hours per day in which we could be, you know, justifying ourselves). thinkChristian nicely uses the transhumanist issue to bring out the distinctiveness of Christianity:

From a transhumanist perspective, it is not merely that humans have certain malfunctions that need to be fixed, but that the human condition itself, with its finitude and limits, including death, is something to be overcome. That is, the problem to be fixed is not something that’s gone wrong with humans; the problem is being human.

Of course, for Christians, this impulse toward transcending our humanity isn’t surprising. In the opening chapters of Genesis, we see God creating humans with power, but also with clear limits. Those boundaries were soon crossed. Though already like God as image-bearers, we are not content; we want to be God. We are often dissatisfied with the fact that we cannot see everything, know everything, or do everything. When we attempt to transcend our human limits by our own plans and means, Genesis 3-11 shows us that murder, violence, and prideful culture-making is the result.

In light of Genesis, we can read the Incarnation as a fascinating inversion of the transhumanist impulse. Sinful humanity tries to leave our humanity behind, in contrast to the eternal, infinite God who willingly becomes human. The Word became flesh and dwelt among us. The Son gave up the unlimited glory and benefits of his divinity in order to become a servant who experienced the ultimate limit: death. Paradoxically, then, the way to transcend our limits is to accept them. The way to overcome death is to accept it, committing ourselves into our Father’s care, just as Jesus did. The Savior we are looking for, the “next human,” as National Geographic would have it, is not a cyborg but a servant. May we see that embracing his path of death is also embracing his path of life.

Extras: We came across an inspiring story of the friendship between grieving Celts pointguard Isaiah Thomas and teammate Avery Bradley. The LARB published an interesting review, especially for academics, of Michelle Boulous Walker’s recent book on Slow Philosophy. Babylon Bee has had some strong content lately, with “Worship Leader Fired After Fumbling with Capo for Three Agonizing Seconds,” “Local Woman Discovers Prayer Request–Gossip Loophole,” and “Pastor Packs Sermon with Record-Setting 78 Euphemisms for Sin.” And over at vice.com, Camille Paglia keeps on doing what she does – insight alloyed with provocation. Finally, in humor, Mallory Ortberg delivers a reflection on the pervasiveness of the Fall, in the course of Calvinistically scolding her dog:

Who’s a good boy? Who’s a good boy? Not you. You are a dog who exhibits signs of total depravity, and has as yet failed to produce any outward symbols of the inward condition of grace. I begin to suspect that you, dog, are not a member of the elect.

Would a dog who has experienced unconditional election bark at my stairs for no reason for thirty minutes? There was nothing on the stairs. Why, then, did you bark? Were you fulfilling the commandment found in Lamentations 2:19, “Arise, cry out in the night: in the beginning of the watches pour out thine heart like water before the face of the Lord”? Because I do not believe that injunction applies to my stairs. This was not speech but noise, and noise without purpose; though you bark with the tongues of men and of angels, if you have not charity, you are become as a resounding gong, or a clanging cymbal. Remember, dog, the words of the prophet Amos (chapter five, first twenty-three): “Take thou away from me the noise of thy songs; for I will not hear the melody of thy harps.

And finally, for something completely different,

https://youtu.be/trDnp3dWlXk

[1] TNY’s article (perhaps based on Dreher’s book) briefly conflates nominalism with the correlated, but distinct, idea of voluntarism. Also, it defines “realist” in opposition to “nominalist,” but then uses both terms pretty loosely later on. Caveat emptor.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply