In the genetic funnel that began my life, the English came in 1634, and the Dutch a few months later. The Germans came in annual waves as religious Pietists or farming Protestants between 1720 and 1750, and again as song- and beer-loving Papists in the 1860s. My cheek swab and my waist tell a story of German rotundity with just fractional admixtures of religion and surname. The Italians arrived with their mozzarella in the famous year of 1901. By the time I was born in Pennsylvania in 1979, we had somehow avoided the temptations of Manifest Destiny, and clung for 350 unimaginative years to the Atlantic coast—never in those centuries (with a brief Pittsburgh sojourn for two generations of petroleum)—living more than 50 or 60 miles from the ocean. Our trains when we take them have gone from north to south and back in a small space, but not so much from east to west.

One wonders whether the failure to travel very far over the course of four centuries of American life—there was a period in which my mother’s family didn’t move five miles for two hundred years—is a matter of steady habits and stability or just a lack of exploratory thinking. We have never left the ocean that brought us here in several migrations. I begin to wonder if we can.

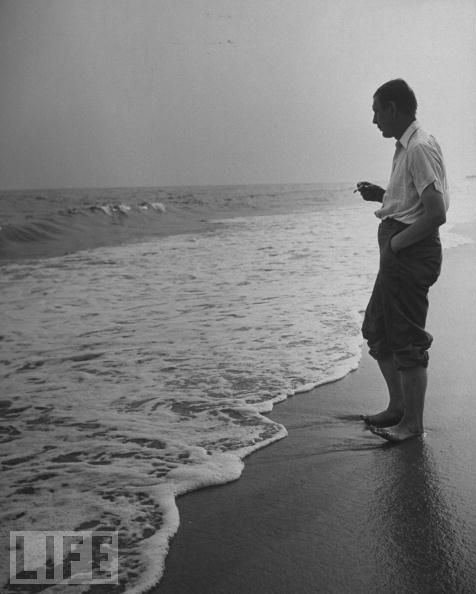

In the last year, the sea has called me in a strange and steady way, pulling me back a few times a month to the margin of the water over which my many families came. I am here again, walking for a few hours each afternoon, naming my children and my friends on the heart I push heavenward as I put each foot in front of the other and attempt a break from the stable of hydras that are my inboxes.

Connecticut does not in most places touch the Atlantic without the intermediary barrier of the island so long they named it Long. One must go to the extreme eastern end of the state, the place where American submarines and Russian spy-boats lurk, to stand on the shore and look the five visible miles toward an unseen Europe that made New England new.

There are fog horns here in thirty-second intervals, and there are also crows who argue against them. There is quiet on this shore, too, a comfort in the sand under my feet—I always take off my shoes, no matter how cold it is—a kind of goodness or at least a reliability in the smell of salt, and in the sickly tide-smells of rotting kelp and harbor detritus.

I turn off my phone. I walk, and think, and pray, and stand, and look at the seashells, the pieces of horseshoe crabs, and at the sky. My life is small against the size of the cold big blue, and I understand myself with some needed perspective as a minor link in a long chain. It is hard to know where the amniotic ends and the mystical begins, or if they become inseparable in the equality and smallness the sea imposes on the person whose eyes are open. How much can the sea wash away, and what does it carry, and what has it brought, and what do I matter here?

I came to this shore after midnight on Christmas, the first Christmas in my life I have spent entirely alone. The sky was clear, the water was open, the stars unusually bright for this part of Boswash, the moon nearly full. It was a Christmas entire and true, but there were no jingle bells from dawn to dusk—and in fact I didn’t speak to a single person on the Day itself with whom to exchange out loud the greetings of the season. It was a Christmas of quiet darkness against which I prayed for a light that was manifest only in the round moon and in the dawn. There was the cold, the accepted solitude of walking alone with bare feet on wet sand, the uncomfortable confronting of emotional or religious certainties against the clarity of a silent sky and the knowledgeable tides beneath it.

There was also an aching contentment in the awareness that one’s life is at best a stable in which the Christchild can be born, that one’s palms are the places to welcome him, that one’s voice becomes a way to speak of that Child, that one’s friends are the occasions to honor him in gentleness and happiness and goodness, in strength and in faithfulness, in mirth and in the telling. It would not be wrong to say that there was an inversion for me this year between the Star of Bethlehem and the Moon of Stonington.

As I walk on the coast, I have no inclination to reverse the migrations—what would I do, with old roots here, and deracinated roots there? My daughters, young shoots, are here, and our nearness is the best marrow of my life.

That is not the longing that draws me to the salt and the spray. What I have sought and found here is rather a hard resetting of my emotions. The proximity of the ocean shore is an opportunity to calibrate my own significance against the immensity of the natural world and the wideness of my community of friends and neighbors, and also to stand within the quiet I need in daily life. In its steady waves, the sea breathes. I listen to it in them, and I try to learn their ancient lessons of calm, of cleansing, of perspective, of return, of renewal.

COMMENTS

2 responses to “Gratitude for the Waves”

Leave a Reply

This hits on so many levels: Richard needs to write more!

Beautiful.

Very beautiful.