Here’s a beautiful reflection from our friend, Elsa Wilson.

We don’t do a lot of waiting nowadays. A few extra seconds of Internet load time merits a complaint call. We don’t like waiting, but we’re asked to do a lot of it. We especially don’t like waiting when it comes to movies. We tend to favor fast cuts and snappy punch lines. These movies “reward” the viewers (and also usually the characters) for their time by pairing questions with answers, effects with causes, and situations with explanations. There are actually storytelling formulas that dictate how long the viewer should be left to wonder before the truth is revealed, how long the protagonist should have to struggle before their want is achieved. This is effective storytelling, and a lot of fun, but sometimes we’re left to ask why our own lives aren’t resolving in this “normal” amount of time. The longer we wait, the more our faith is tested. We can’t skip to the end of our stories.

A rather obscure short film called Wavelength (1967) hits the nail on the sometimes aggravatingly slow head of faith in the unseen – faith in what lacks obvious value. In the film, we wait for what doesn’t seem worthy. We wait for something whose worth is not proven. In most films, we put our faith in a protagonist whose resolution we feel we will see at the end (and in a decent timeframe). But faith depends on things not seen.

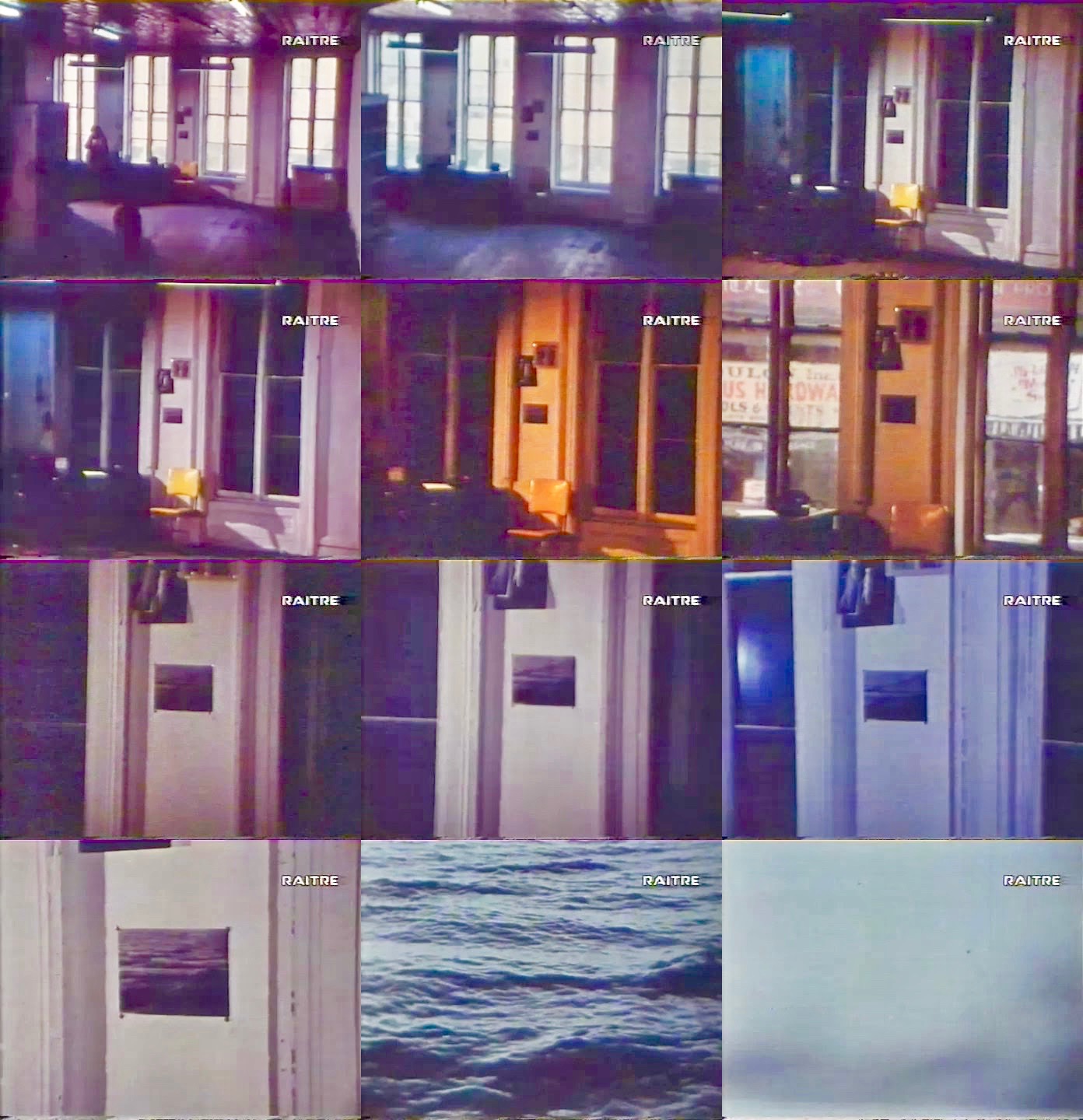

Speaking of ‘seen’ and this film, not many people have. Wavelength reveals something about what it means to wait on God. Director Michael Snow asks us to be patient, and to limit our sight – not only narratively, but also technically. Snow does not give us the luxury of a camera pan (something we subconsciously take for granted). Rather he gives us a little square of a world that does not waver. The camera never moves – it only zooms in at an almost imperceptibly slow rate. For 40 minutes. Maybe that’s why not many people have seen it.

If there’s something worth waiting for in the end, the worth is hidden from us.

The film’s value rests less in the audience’s patience, and more in the director’s. Of all the content and objectives that directors could display, Snow chooses “the least of these.” The subject of Wavelength is a rather uninteresting room. The camera points toward a certain one of four walls, and the zoom moves from a medium wide shot of the entire room to a close-up of a small picture hung on the wall across from where we started. It’s almost as if Snow is saying, “There’s something I want to show you here, something worth taking the time to see. Bear with me.”

Outside the windows of the room we can catch glimpses of the mundane comings and goings of a small side-street in a city. But the camera never gets distracted; it just keeps inching towards the wall across the room. It doesn’t change our frame of reference, but only magnifies and specifies it.

In a salvation-by-works world, there would be little point in watching a blank room – it has nothing to offer, no face value. But Snow’s intentionality doesn’t feel pointless. He doesn’t seem to be wasting our time — and neither does God, who acts in a similar way.

There seems to have always been a kind of holiness connected to the slow zoom of God’s plot: Abraham’s offspring, the “long lay the world in sin and error pining” of so many prophets and prophesies, the anticipation and trust that followed the Annunciation, that implication in the Beatitudes that promise and gratification aren’t always plot point 1 and 2 consecutively (those who mourn shall be comforted…at some point).

The slowest zoom of course started on Good Friday. It seems to be a condensed version of creation – when God existed but the window that would reveal His glory to man (and in man) was still a secret. His connection to Earth was hovering (maybe alive, maybe not) over the face of the deep, formless and void. The disciples were waiting in the darkness that followed the crucifixion, though perhaps their perspective wouldn’t call it that. “Waiting” implies a gratification, and who knows what the disciples believed or stopped believing in those three days.

Often, it seems that God asks us to wait for something we can’t control or even fully understand. And sometimes it feels as agonizing as those 40 minutes of slow zoom towards something that seems so anticlimactic. Snow’s film shows us a refinement by a very low-heat fire. And it uncovers some truths about faith.

First, the slow zoom is revealing. The camera frame and lack of movement both function to reveal our limited perspective. We can’t see past the camera’s frame. The “pan” is beyond our ability as humans. Snow holds that power as director and artist, and decides not to use it. Not being able to see the big picture reminds us how small we are. The restriction humbles us, and reminds us of all that we cannot control. In a way, we see all that we can’t see. At one point in the film, a woman acknowledges a dead body on a part of the floor hidden from our view. We can’t see it, so we have to believe the woman’s remark–it’s faith not-by-sight.

Second, the slow zoom is redeeming – giving value to something that otherwise seems valueless. Part of the tedium of the film is the filmmaker showing grace to what doesn’t seem worthy. He asks us to stare at something that would normally only be glanced at as background. Snow isn’t showing us something new, but something common in a new way. He isn’t explaining the value, but he’s asking us to give our attention to something that we normally wouldn’t. He accomplishes this by where he chooses to place the camera. It’s about his perspective as much as it is about ours.

So what is so valuable? The film ends with a close-up of a photo we have been inching toward for 40 minutes. It’s on the wall opposite us – a photo of water. It was too far away and mundane to notice before. It’s as if all the tedium and slow intention of the film was just to show us one detail we never would have seen otherwise. We hear a static-y “Strawberry Fields” from a radio – something we’ve heard before, but never like this. This time, we are not listening to it, we are listening to others listen to it. And it doesn’t make sense. Why can’t we cut to the action? It feels miraculous at the same time that it feels tedious. And of course, we start asking why.

At the end of Wavelength, there isn’t a big reveal. There’s no typical payoff like we’re used to. There is just a tiny picture of a wavy sea. It’s not what we expected, but it’s something. Something more than an empty room.

The mystery isn’t solved. We aren’t told why we had to deal with uncomfortable time, sound, and camera movement. Sometimes all of our efforts end with something we can’t explain. We wait the whole film in expectation of something we feel we deserve. We itch for a big reveal and perhaps congratulate ourselves for not giving up before it happens. But Snow doesn’t reward us in the way we think he should. He rather shocks us by showing grace to what has no surface value. Snow says there’s something valuable enough about a strange and rather dull room to give it 40 minutes of screen time and then end with a puzzling picture on its far wall. Why, we ask repeatedly, would there be a 40-minute film about a room? It’s insignificant. But we were insignificant once, too. When we realize this, the film can become about us – that while we were (and are) still sinners, we were (and are) pursued. Maybe we are the subjects of Wavelength after all.

And yet, we don’t like believing something has value when we can’t see why. When we see the tiny picture on the wall – swaddled in waves and strange noise – we ask, “Is this really what we waited for?” Like Snow’s revelation of the sea, the revelation of God in Christ, beginning with his humble birth, was the eons-old answer that didn’t look like much of an answer. It didn’t make sense. It was small, seemingly insignificant. Imagine bowing to such a tiny anticlimax. Long lay the world, and then there were just more questions. It would be 33 years of slowly zooming in on the value and worth of it all — and at the cross, it seemed, there were just more questions.

Towards the end of the film, the instrumental soundtrack (it doesn’t feel like music) reaches an almost unbearable surge of noise – even once the picture of the sea has filled the screen. We meet the point of the film, and we still aren’t given rest. The noise reaches a level that made me visibly cringe in my seat – until with a soft surrender, the noise slips into silence, with exactly one minute of film left to go. The sea is calm, with a few frozen waves that look almost like our furrowed brows might if we realized there’s an answer we never guessed.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply