My mother and father always attempted to instill into me and my brothers an appreciation for culture. Mom was and remains extremely well-read in classic literature, hailing Steinbeck as her favorite; she enjoyed foreign cinema and took me (while in the womb) to an Ingmar Bergman film festival; she could reference renowned plays and decided to middle-name me after Neil Simon; and her record collection lined the living room perimeter containing everything from Funkadelic to Simon & Garfunkel, Temptations, Barbara Streisand, The Police, Rick James, etc…

My mother and father always attempted to instill into me and my brothers an appreciation for culture. Mom was and remains extremely well-read in classic literature, hailing Steinbeck as her favorite; she enjoyed foreign cinema and took me (while in the womb) to an Ingmar Bergman film festival; she could reference renowned plays and decided to middle-name me after Neil Simon; and her record collection lined the living room perimeter containing everything from Funkadelic to Simon & Garfunkel, Temptations, Barbara Streisand, The Police, Rick James, etc…

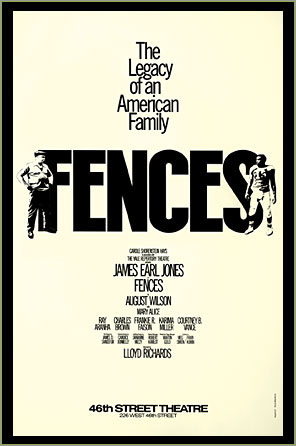

But I think the most significant (though at the time not fully appreciated) exposure came when I was about 11 years old. It was 1989, and though I had convinced my parents to take us to Northridge cinema to see House Party, they also made sure I attended two classic stage productions at one of our local theater houses. One was Porgy and Bess and the other was August Wilson’s Fences – a 1983 Broadway play starring James Earl Jones and Mary Alice as Troy and Rose Maxson, the patriarch and matriarch of a middle class American family seeking to establish an ethnic, national, and familial identity in the transitional period between Jim Crow’s deconstruction and the simultaneous acceleration of the Civil Rights movement.

Set in 1950’s Pittsburgh, Wilson’s drama exists as part of a ‘Century Cycle’ in which each of ten plays he wrote corresponds to and depicts characters in a different decade of the 20th century. Fences, the sixth installment of his ‘Pittsburgh Cycle’ won both the Tony and Pulitzer awards in 1987 and consequently enjoyed a revival in 2010 when Denzel Washington and Viola Davis portrayed the Maxsons in a second Broadway run. Shortly after their Tony award winning performances, Washington contracted with HBO to transfer all ten of Wilson’s plays to the silver screen. 2016’s Fences which opened last Christmas Day represents the first chapter of this ambitious project.

Thought provoking and engaging as they are, the play’s racial and cultural considerations of what it means to be American and to share in the ever elusive and effervescent ideal of ‘the American Dream’ merely serve as a contextual backdrop for more transcendent themes of cross-generational tension, questions of manhood and identity, and ultimately father-son dynamics. It is here where we see Law and Grace wrestle, struggle, and work out their implications primarily through the filter of Troy’s relationship with his second-born son, Cory.

Typical idealistic high school senior, Cory Maxson does everything to please his father. As his mother Rose remarks in Fences’ first act, Everything that boy do…he do it for you. He wants you to say “Good job, son.” That’s all. Though preoccupied with ambitions of going pro in the NFL, Cory constantly practices his swing on a raggedy baseball tethered to a backyard tree limb. Suspended, stationary, and retired from its original use, the worn out ball mirrors Troy’s failure to fully self-actualize as an American ball player. Maxson often relives his long-gone glory days through embellished narratives and boisterous reminiscences as he sips gin with lifelong friend and fellow sanitation worker, Bono, after a long day of collecting other people’s trash.

Typical idealistic high school senior, Cory Maxson does everything to please his father. As his mother Rose remarks in Fences’ first act, Everything that boy do…he do it for you. He wants you to say “Good job, son.” That’s all. Though preoccupied with ambitions of going pro in the NFL, Cory constantly practices his swing on a raggedy baseball tethered to a backyard tree limb. Suspended, stationary, and retired from its original use, the worn out ball mirrors Troy’s failure to fully self-actualize as an American ball player. Maxson often relives his long-gone glory days through embellished narratives and boisterous reminiscences as he sips gin with lifelong friend and fellow sanitation worker, Bono, after a long day of collecting other people’s trash.

Troy eventually struck out in both sports and life when he was disqualified from entering the major leagues. While Maxson blames racial prejudice on his inability to advance in sports, Rose reminds him, “You was too old to play in the major leagues… For once…why don’t you admit that?… How was you gonna play ball when you were over forty?” Even Bono agrees Troy just came along a little too early in life to succeed in major league ball.

Cory identifies with, respects, and wants to be his dad, but he simultaneously wants to be his own man as well. 2015’s Creed captured the same tension where Adonis Johnson lived proudly in his father’s shadow, practicing boxing techniques against a backdrop of images of Apollo’s former matches, while he struggled to carve out a name uniquely his own. Cory Maxson wants his dad’s approval, but fears his judgment. (Spoiler alert) In the play’s final act, the setting places us in the Maxson household in the 1960’s on the day of Troy’s funeral. Cory, who by now has become a decorated Marine, returns home presumably to join the family in paying their last respects. He informs Rose, however that he will not being attending Pop’s funeral. The same young man who earlier agonized over why Pop didn’t like him now insists that for once in his life he has to stand up to Papa and say, “No!” He elucidates further that every time he would hear his dad’s footsteps walking through the house, he would tremble wondering what form of disapproval he would hear “this time.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jhh5UlM1bN0

Cory’s love/hate relation to Troy reminds us of how we relate to the law. We love its promise of glory and long to keep it that we might attain God’s acceptance, but we hate its implacable demands. We hate our father Adam (and are convinced we would not have failed had we been in his place), yet we cannot escape his self justifying ways. More immediately, we don’t want to be our parents, but we unconsciously emulate them and follow their patterns. We swear we’ll never be them and by doing so, we inevitably become them. Cory is inescapably Troy Maxson. We are inescapably our parents. We are inescapably Adam.

Cory wants the glory of sports and that’s all he can see – if he can be great in athletics, he can at least hear Troy say, “Well done.” He has no appreciation for the prudence of learning a trade (something Troy suggests he should do for the sake of job security) and as far as he can see the inclusion of players like Hank Aaron and Wes Covington indicates that integrated teams are making inroads for Blacks. Troy is stuck in the glory of his failed sports days and a mixture of denial, having experienced the sting of Jim Crow, and a sober realistic assessment of racial politics have halted him from moving forward with the changing times. He’s afraid of risk. He’s afraid of failure. If Cory fails…then he has ultimately failed.

At Rose’s behest, Troy consistently enlists Cory’s help in building a fence around their home. Fences function as a metaphor for our striving after the American Dream in which we own our own homes and establish boundaries and identity markers by placing a wooden border around our yards and houses. We know this cliché well: ‘white picket fence, 2.5 children, PTA meetings, minivan, etc…’ In the midst of gin-sipping, Bono pontificates, “Some people build fences to keep people out…and other people build fences to keep people in. Rose wants to hold on to you all. She loves you.”

The fence Troy Maxson is building will ultimately alienate the very people he desperately wants to guard, protect, and hold near. Troy is stuck not so much in baseball fantasies, but in life under the law where you work your way toward the redemption of your past sins. And where you work diligently not to pass those former sins to next generation. Both Troy and Bono refer to their broken relationships with their fathers – Troy physically fought his while Bono’s dad abandoned him in his early youth. Even Rose remarks during the emotionally charged scene in which Troy confesses to impregnating his mistress that she never wanted bastard children in her household due to the rampant fatherlessness that had abounded in her family.

Troy’s determination to break generational curses by way of law only results in straining his relationship with his son. Wilson depicts this culmination of father-son dissolution in a confrontation acted intensely and genuinely by Washington and Jovan Adepo (Cory). According to Troy, Cory’s accusation that he no longer counts in their home due to his infidelity constitutes “strike three” in a progression of tension that gradually mounts between the two.

Employing the motif of baseball as American cultural identity or rather inclusion and acceptance therein, Wilson implies that Troy, who believes he was wrongly disqualified from major league participation due to the color of his skin actually believes he has been disqualified from life by life itself. It’s not so much that ‘the white man’ has done him wrong (though a critical plot point involves his resistance to racial discrimination at the sanitation department where he works)…it’s that life has mistreated him. It’s that God has forsaken him and left him “standing in the same place for 18 years”.

Troy boasts during one of several moments of telling tall tales and exaggerated anecdotes that he has met and sparred with death himself. We see soliloquies and monologues in which he dares death to confront him for a round of fisticuffs as surreal punctuated moments in the narrative comment on our protagonist’s gradual demise. Troy believes he can beat death. He believes he can succeed at life under the law. He believes that through working hard to provide for his family, convincing Cory to get a trade instead of chasing sports, through staying away from jazz clubs where shiftless derelicts run numbers and gamble, he can overcome death and find life instead. If he can’t have access to the American Dream through baseball, he will “build me a fence around what belongs to me!” But Troy loses his fight with death. And yet this loss ushers in the completion of Cory’s manhood via the bestowal of grace.

Cory is like Troy – he believes manhood and identity are established by way of law. In his case, keeping the law comes by way of trying to resist it. When Rose comments that he’s just like his dad, he replies, “I’m not Troy Maxson! I don’t wanna be Troy Maxson!” We never overcome the sins of our fathers by pretending we’re not made in their same broken likeness. We never overcome the Old Adam by finally, eventually pleasing God with law keeping. Cory couldn’t win: he couldn’t earn his father’s explicit approval by any of his life choices. He cannot overcome what he inherited from his father by denying his father’s crooked DNA.

Rose graciously reminds him that his father was radically flawed – he metaphorically cut when he embraced her, he disappointed all her hopes and aspirations, and betrayed their sacred vows. But she loved him, she understood him, and ultimately she validated him because she knew he was a fallen sinner doing the best he could to love other fallen sinners. In unofficially eulogizing Troy, Rose not only models what takes place during justification where a good word is literally spoken over the dead (we died to sin), but she also allows Corey to hear the voice of grace after the voice of law has died. Paul reminds us in Romans 7 that we who were once bound under the law have been set free because we died to what held us captive. We can hear good news because we died to the law’s accusations. Cory can hear and receive grace after Troy has died. It is by forgiving Troy’s inability to express love that Cory can enter into the fullness of his manhood.

Rose graciously reminds him that his father was radically flawed – he metaphorically cut when he embraced her, he disappointed all her hopes and aspirations, and betrayed their sacred vows. But she loved him, she understood him, and ultimately she validated him because she knew he was a fallen sinner doing the best he could to love other fallen sinners. In unofficially eulogizing Troy, Rose not only models what takes place during justification where a good word is literally spoken over the dead (we died to sin), but she also allows Corey to hear the voice of grace after the voice of law has died. Paul reminds us in Romans 7 that we who were once bound under the law have been set free because we died to what held us captive. We can hear good news because we died to the law’s accusations. Cory can hear and receive grace after Troy has died. It is by forgiving Troy’s inability to express love that Cory can enter into the fullness of his manhood.

Fathers are important and these days, there’s a need (in Black communities especially) for men to be actively present in our son’s lives providing guidance without failing to communicate affirmation. But mothers are not insignificant and never have been (cf. Genesis 3:15, Matt 1:3-6, 16). Rose’s fence of grace, humility, and forgiveness kept the family together despite Troy’s many transgressions. “Jesus Be a Fence” she sings during a scene in which she hangs laundry in the backyard. And He is a fence. A better fence than the ones we build. Our fences tend to be defenses that keep people out – the more we try to love, the more we fail. The more we try to not pass on ourselves to our kids, the more we corrupt them. It’s easy to feel the pressure as a dad to not visit the sins of the fathers to your sons and daughters. But to have that burden is unbearable. The good news is that Jesus became the veil our Heavenly Father tore down so that the fence would no longer separate us from Him. Yes, Jesus be a fence around my children…protecting them from my broken legacy and enclosing them in the family of God forever!

COMMENTS

One response to “Fathers, Sons, Law, and Grace in August Wilson’s Fences”

Leave a Reply

Wow, Jason. Wow. This spoke to me powerfully.