I used to have a really great memory. It wasn’t the kind of memory that was featured on Dateline NBC, where people with photographic memory can recall very specific details of very specific dates in their lives. But I can remember details of very early events in my life, and my memory came in handy when I had to memorize facts and dates for tests in school. For as long as I can remember (heh), I knew that this kind of memory was a mixed bag – a blessing and a curse. I could memorize the multiplication table with very little effort, but I could also feel the burning shame all over again when I remembered a time when I got in trouble for something. Having a great memory and having some level of anxiety didn’t always feel great, and I often wished for one of those Men In Black wands that could erase a memory so I wouldn’t have to re-live it.

When I got married, the double-edged sword of a good memory presented itself again. I could remember exactly what we needed at the grocery store, whose party we were supposed to attend on Friday evening, and when the garbage was supposed to go out to the curb. This was great, until I got frustrated with my husband for not having the same level of recall that I had, or when I drudged up old grudges that I couldn’t seem to forget. My husband called my memory my “super power,” but I thought of it more as a liability sometimes.

After we had children, my memory started to fade a bit. I’ve heard other mothers hypothesize that memory cells leave a mother’s body during childbirth with the placenta. I think it’s probably more a combination of the natural aging process, lack of sleep, and blunt force trauma to the head from co-sleeping with a mobile toddler. Either way, after two children, my memory wasn’t so super-power-charged as it was before. When I worried about it out loud to my husband and friends, they assured me that this is how “normal” people felt, and my husband jokingly started calling me a “mere mortal” without my superpower. On the one hand, it was disorienting to lose a tool that I had relied on for years. On the other hand, I tried to find something freeing about now having the burden of an anxious memory-filled mind.

I started to see another gift in forgetting whenever anyone would approach me at church with a vocabulary I didn’t speak. “There’s a bat in the sacristy,” my friend said to me one Sunday.

“I don’t even know what that means,” I replied honestly.

“It’s up the steps from the nave,” she explained earnestly.

“I’m still lost,” I told her. “But get rid of the bat before I wander in there – wherever ‘there’ is. Please.”

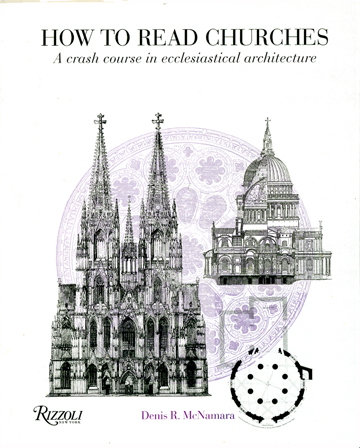

Even when I had an above-average memory, I had a block for church architecture terms. I cannot tell the difference between the nave and the narthex, or the sacristy from the flying buttresses. These are words I should know, from mere association. I’m married to a priest at a large Episcopal church. My dad is a priest. My brother is a priest. My brother-in-law is a priest. My ignorance is the equivalent of a Navy wife not knowing what a port is. These words not only don’t matter to me, the words themselves represent a huge stumbling block to me because I wouldn’t be able to communicate with any so-called “outsiders” if I used them. If I told a newcomer to meet me in the nave, they may never come back, just for lack of clear direction. The wall in my brain keeping the words out might just be the avenue that I need to let others in.

Even when I had an above-average memory, I had a block for church architecture terms. I cannot tell the difference between the nave and the narthex, or the sacristy from the flying buttresses. These are words I should know, from mere association. I’m married to a priest at a large Episcopal church. My dad is a priest. My brother is a priest. My brother-in-law is a priest. My ignorance is the equivalent of a Navy wife not knowing what a port is. These words not only don’t matter to me, the words themselves represent a huge stumbling block to me because I wouldn’t be able to communicate with any so-called “outsiders” if I used them. If I told a newcomer to meet me in the nave, they may never come back, just for lack of clear direction. The wall in my brain keeping the words out might just be the avenue that I need to let others in.

I started seeing my lack of church architecture vocabulary as a spiritual gift – a holy forgetfulness. If I could remember other things, but not those words, was there a reason for my mental block? Even with my diminished post-childbirth memory skills, I still have the ability to learn new things, as evidenced by the fact that I learned to do my job efficiently, I enrolled the children in school with all the requisite forms and letter-coded days, and I seem to have taught myself how to use a pressure cooker without blowing up the house. But the names of church rooms still trip me up, as if I have a huge wall in my brain keeping them out. Maybe in my role as “The Rector’s Wife,” and a person who is allegedly supposed to know these things, there was some freedom in not remembering them.

Is this blessed forgetfulness anything like forgiveness? I’m not the first person to ponder this, of course. In Miroslav Volf’s The End of Memory: Remembering Rightly in a Violent World, he recounts ancient and modern thinking about the relationship between forgiveness and forgetting, and distinguishes between “memories in the world to come and memories in the present world.” Volf wisely values memory in the present world for the “open question” of justice as a solution to violence. Even in forgiveness, there are reasons not to forget.

I appreciate that serious reflection, and I can even appreciate the value of church architecture terms. I hold out hope, though, for Volf’s “world to come,” where my sins will be as forgotten as all of the words I can’t remember.

COMMENTS

4 responses to “Holy Forgetfulness”

Leave a Reply

Awesome….again! You are remarkable in so many ways!

Love this so much! And it isn’t just the architecture terms that are challenging. Years ago when my husband worked as a correctional officer, he became Senior Warden at our Episcopal church. Numerous family and friends thought he had gotten a big promotion at work.

Lol

Great piece. Have you read Noon to Three by Robert Capon? I love how he pictures our lives as being reconciled to God in Christ so that our sins are no more but our actions and hence our remembering of them are made right in Christ.