Hope for forgiveness and the Kingdom of Heaven beyond our human moral bankruptcy has been replaced by progressive Utopian visions where well-adjusted inhabitants are provided for in an earthly paradise. But the knowledge of who we really are and the true state of our predicament surfaces regularly in our cultural history, if we are paying attention. The visual arts especially will occasionally provide a map of the darkness we travel through. It hardly matters where or when we look, but the dark side of 19th century Romanticism is a good place to start, since a current runs from there through Nietzsche to the contemporary tide of postmodern nihilism. One painting in particular reveals the awareness of our existential predicament that our more intellectual discourses attempt to cover over: The Raft of the Medusa.

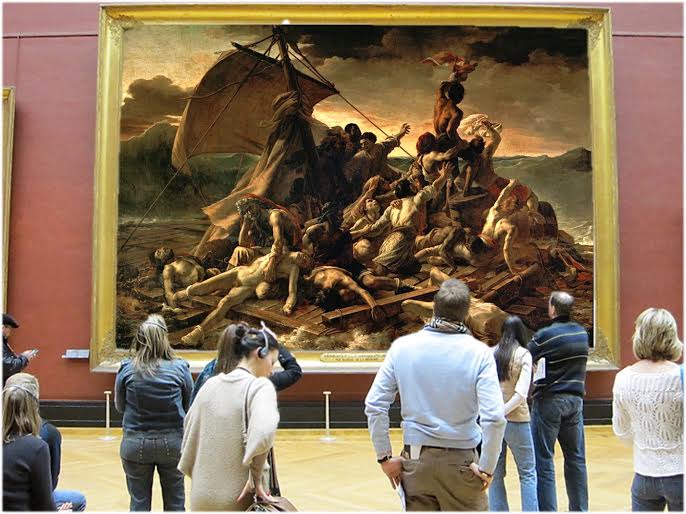

The Raft of the Medusa is an imposing oil painting by the French artist Théodore Géricault. Hanging in the Louvre, it measures sixteen feet high by twenty-three feet wide, quite a bit larger than life. Acknowledged as one of the great masterpieces of early French Romanticism, the painting is a true tour-de-force, if an obsessive one.

The scene Géricault shows us is a raft of survivors from the sailing frigate Medusa. In 1816, the ship ran aground on shoals about sixty miles off the west coast of Africa, reportedly due to the incompetence of her captain, a political appointee of the French bureaucracy. The captain and crew manned the stranded ship’s boats, which had only enough room for about 250 of the 400 passengers and crew the Medusa carried. They set the rest of the passengers, nearly 150 men and one woman, on a makeshift raft, with the intention of making for the coast with the raft in tow. For reasons hazy in the historical record, the sailors soon cut loose the tow ropes and left the raft behind. With little food and water, the cast-offs abandoned on the raft drifted for thirteen days before being rescued. Only fifteen survived the ordeal, and they told a story of maddening thirst, despair, mutiny, murder, and cannibalism. The raft, a makeshift assemblage of spars, broken masts, and spare lumber, barely held itself above the sea, and the strong soon forced their way to the center and claimed the highest section. The weakest were pushed to the submerged edges and soon were claimed by the sea. It was a closed, forced process of selection, both natural and unnatural, but the fitness of those who remained said nothing of their worthiness.

The event itself caused a scandal for the newly restored French monarchy. Géricault, twenty-seven years old with some earlier small successes, convinced himself that a monumental painting of the incident would secure his reputation and advance his career. He was right on both counts. But The Raft of the Medusa, if it did not actually kill him, fed his dark obsessiveness. He died only five years after completing the painting in 1819, never having exceeded or even equaled this achievement. A low-relief bronze sculpture of The Raft of the Medusa adorns his tomb.

Géricault painstakingly researched the record of events. He interviewed survivors of the Medusa and had the carpenter who built the raft construct an accurate scale model for him. From the relative safety of the French Atlantic coast, he carefully observed wind and waves, sky and storms. He became a student of death. A local hospital and its medical students provided corpses and even severed heads and limbs which Géricault carefully sketched. In detail, he reproduced the contours and masses of dead bodies and faithfully copied the pallor of skin and the peculiar rigidity of death.

The completed painting’s composition is dominated by strong diagonal lines of sight and two pyramid groupings of figures and picture elements. The raft occupies nearly all the lower half of the painting; the rough boards of its construction slanting from upper left to lower right across the picture plane. Géricault shows the raft as it really was, low in the water, partially submerged, and completely at the mercy of the swells and breakers that surround it. Our eye is first drawn to a grouping of figures near the bottom of the painting, where a corner of the raft touches the edge of the canvas and is obscured as it merges with the sea. This scene is a front-lit tableau of the dead and dying, and by the way he composes the foreground of his painting Géricault means for us to imagine ourselves among them. On the left, a despairing man grips the chest of what can only be the body of his dead son. The son’s legs, locked in the rigor of death, hang off the raft diagonally. This compositional line is matched on the opposite side of the painting by a torso trailing head-first over the side of the raft toward the lower right corner. We follow the legs off the raft, but we do not see the face of this anonymous corpse, obscured by a drenched cloak like a grave shroud. Moving back along the same line we are led to center of the raft and nearly the exact center of the canvas. We see a man’s face upturned toward the upper right corner. He has a fixed unfocused stare, but it draws us to the figure holding this man up off the deck of the raft with his left arm. This kneeling man strains his body and stretches his right arm upward. His hand seems to grasp at a group of figures to the right who form a compositional pyramid.

At the top of this pyramid, a man waves his red shirt toward the horizon. His companion on the right does the same, his white shirt blowing in the wind. We see other outstretched hands and more faces straining toward the horizon, but at first we do not notice at all the focus of their attention. But then, there, just below the elbow of the man waving the white shirt is a small triangular daub of darker paint sitting just on the line between a somber green sea and a light ochre sky. In the whole massive painting, this slight depiction of a sailing ship appears no more than three or four inches high.

Géricault has seemingly chosen to portray the moment just before the survivors of the Medusa were rescued. But something is wrong here. The rescue ship itself is barely discernible, perched on the edge of the horizon line, well toward the right side of the painting. The ship seems to be sailing away from the raft. While the compositional diagonals and the straining figures themselves carry our eyes toward the right horizon, the raft itself is being pulled and dragged by the wind in the opposite direction. A second and darker compositional pyramid on the left encloses a seated man clutching his head in despair, but also a quartet of figures with expressions of hope, having sighted the rescue ship. The men are grouped around a short jury-rigged mast, whose shrouds and stays form the enclosing lines of the pyramid. At the top of the mast a full sail stretches and billows from a yardarm, carrying the raft to the left and away from rescue. Just beyond the lower left corner of the sail, the dark green mass of an immense wave rises, which we know will break and crash over the survivors in the next instant. We are witnesses to a moment frozen in time, suspended over the abyss.

The Raft of the Medusa is not about hope and rescue; it is about despair and death. It is Hell artfully rendered. Whatever the actual history, we know from the depicted situation that the hope of the raft’s passengers is false; this is a voyage of the damned. Eugène Delacroix, Géricault’s younger friend and colleague, borrowed the vision and picture elements from The Raft of the Medusa in his painting for the 1822 Paris Salon, Dante and Virgil in Hell. The scene is taken from Dante’s Inferno. Dante and Virgil share the passage of the damned as they are ferried across the raging river Styx to Dis, the City of the Dead. They are tourists in Hell. Virgil, Dante’s guide, stands calmly in the center of the small craft as Dante draws back, terrified by the anguished and twisted bodies clinging to the sides, yet reassured by Virgil’s hand clasping his own. Delacroix’s painting is an aesthetic commentary on Géricault’s. Géricault’s painting is a commentary on the human condition: present misery and a worse future; surrounded by desperation, madness, and death; abandoned and submerged in an uncaring ocean.

We could dismiss Géricault’s vision as the sort of fevered poetic melancholy shared by all the death-wish Romantics, from Byron and Shelley to Jim Morrison and Kurt Cobain; nothing more than an obsessive psychological pathology. It is, after all, just a painting; a tour of Géricault’s mind, maybe, but not a description of the real world. For most of us most of the time, Géricault’s things never seem this dark and hopeless. When we do spy the wreckage of other lives and worlds, even when we reach out to help, we are Dante and Virgil, not the tormented souls grasping the gunwales of a doomed ferry. But we forget we are sailing the same ocean, pulled by the same currents, pushed by the same winds. Are we not all voyaging into the same darkness, in desperate need of rescue?

COMMENTS

2 responses to “An Artful Hell: Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa”

Leave a Reply

However as Gericault’s life was cut tragically short by prolonged illness and several riding accidents, his legacy could only be carried on and built upon by the more anarchic Delacroix.

Diverging from the traditions of Christian art and traditional depictions of war, it has no distinct precedent, and is acknowledged as one of the first paintings of the modern era.