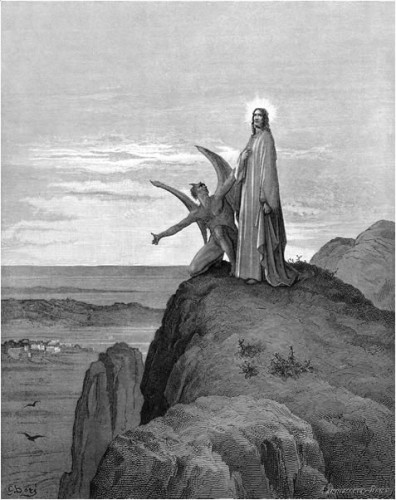

In church yesterday, we read the “Temptation in the Wilderness,” the passage where Jesus is tempted to turn stones to bread, to throw himself down from the Temple in a spectacle, to kneel to the devil in exchange for infinite power. Jesus has fasted forty days, but he does not waver.

The sermon at our church focused more on the form (and less the content) of the interchange, and distinguished the sentence structure of the devil’s temptations, versus the sentence structure of Christ’s replies. I had never noticed this before, but each of the tempter’s promises are conditional: “If…then…” If you just do X, you will have Y.

The sermon at our church focused more on the form (and less the content) of the interchange, and distinguished the sentence structure of the devil’s temptations, versus the sentence structure of Christ’s replies. I had never noticed this before, but each of the tempter’s promises are conditional: “If…then…” If you just do X, you will have Y.

I suppose I never noticed it because it is pretty much the standard framework of any conversation dealing with the future. If you study for the test, you will get a better grade on the test. If you badger your spouse enough times about the kind of cheddar you like, he/she will remember said cheddar the next time he/she goes to the store. And if you just had the cheddar you wanted, by God, and not the cheddar you wound up with, then you’d actually be able to enjoy your afternoon. The future is conditional, right?

Well, no. That is wrong. The future is not conditional. Not on most counts. We do not know what will make our afternoon enjoyable any more than we know how long the housing market will be where it is. But it doesn’t stop us from believing it’s the way the world works. Or the way God does.

Cut to the amazing, heart-wrenching New York Times op-ed this Sunday from Duke Divinity professor, Kate Bowler, “Death, the Prosperity Gospel, and Me.” Bowler, who was diagnosed with Stage 4 cancer, also (ironically) just wrote a book on the American theology popularly known as the “prosperity gospel.” Her book is called Blessed. In coming to grips with her own mortality, Bowler sees in stark detail the absurdity of such conditional thinking.

I learned that the prosperity gospel sprang, in part, from the American metaphysical tradition of New Thought, a late-19th-century ripening of ideas about the power of the mind: Positive thoughts yielded positive circumstances, and negative thoughts negative circumstances.

Variations of this belief became foundational to the development of self-help psychology. Today, it is the standard “Aha!” moment of Oprah’s Lifeclass, the reason your uncle has a copy of “How to Win Friends and Influence People” and the takeaway for the more than 19 million who bought “The Secret.” (Save your money: the secret is to think positively.) These ideas about mind power became a popular answer to a difficult question: Why are some people healed and some not?

The modern prosperity gospel can be directly traced to the turn-of-the-century theology of a pastor named E. W. Kenyon, whose evangelical spin on New Thought taught Christians to believe that their minds were powerful incubators of good or ill. Christians, Kenyon advised, must avoid words and ideas that create sickness and poverty; instead, they should repeat: “God is in me. God’s ability is mine. God’s strength is mine. God’s health is mine. His success is mine. I am a winner. I am a conqueror.” Or, as prosperity believers summarized it for me, “I am blessed.”

One of the prosperity gospel’s greatest triumphs is its popularization of the term “blessed.” Though it predated the prosperity gospel, particularly in the black church where “blessed” signified affirmation of God’s goodness, it was prosperity preachers who blanketed the airwaves with it. “Blessed” is the shorthand for the prosperity message. We see it everywhere, from a TV show called “The Blessed Life” to the self-justification of Joel Osteen, the pastor of America’s largest church, who told Oprah in his Texas mansion that “Jesus died that we might live an abundant life.”

…Blessed is a loaded term because it blurs the distinction between two very different categories: gift and reward. It can be a term of pure gratitude. “Thank you, God. I could not have secured this for myself.” But it can also imply that it was deserved. “Thank you, me. For being the kind of person who gets it right.” It is a perfect word for an American society that says it believes the American dream is based on hard work, not luck.

This distinction, for Bowler or anyone like her facing the Jobean weight of un-asked-for suffering, is the difference between Oprah Optimism and Christianity, or better, bad news and Good News. This distinction–between a gift and a reward–shows self-help optimism for the fallow endeavor it is. While it may allow you to feel responsible for the good day, its contingency on you will bite you on your worst day. Certainly, no amount of positive thinking is enough to stave off metastasis–but what’s worse, under the conditional framework of the prosperity gospel, your metastasis may be proof of something. It may mean you didn’t believe hard enough or think positively enough.

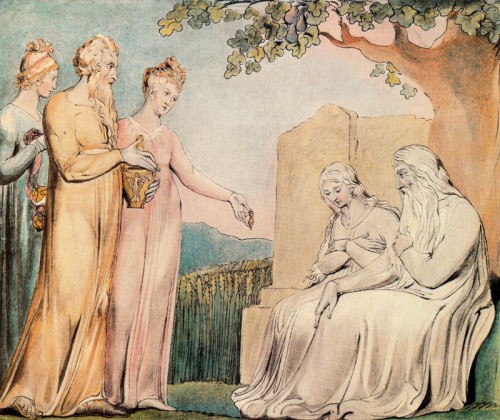

Bowler talks about the illuminating power of mortality to expose the human need for explanation. #Blessed is a facile way of understanding that good comes out when we put good in. Like Job’s comforters, we seek simple reasons for the suffering of the world. It makes us feel safer. But as Bowler writes, “God is always, for some reason, going around closing doors and opening windows.”

The prosperity gospel holds to this illusion of control until the very end. If a believer gets sick and dies, shame compounds the grief. Those who are loved and lost are just that — those who have lost the test of faith. In my work, I have heard countless stories of refusing to acknowledge that the end had finally come. An emaciated man was pushed about a megachurch in a wheelchair as churchgoers declared that he was already healed. A woman danced around her sister’s deathbed shouting to horrified family members that the body can yet live. There is no graceful death, no ars moriendi, in the prosperity gospel. There are only jarring disappointments after fevered attempts to deny its inevitability.

The prosperity gospel has taken a religion based on the contemplation of a dying man and stripped it of its call to surrender all. Perhaps worse, it has replaced Christian faith with the most painful forms of certainty. The movement has perfected a rarefied form of America’s addiction to self-rule, which denies much of our humanity: our fragile bodies, our finitude, our need to stare down our deaths (at least once in a while) and be filled with dread and wonder. At some point, we must say to ourselves, I’m going to need to let go.

CANCER has kicked down the walls of my life. I cannot be certain I will walk my son to his elementary school someday or subject his love interests to cheerful scrutiny. I struggle to buy books for academic projects I fear I can’t finish for a perfect job I may be unable to keep. I have surrendered my favorite manifestoes about having it all, managing work-life balance and maximizing my potential. I cannot help but remind my best friend that if my husband remarries everyone will need to simmer down on talking about how special I was in front of her. (And then I go on and on about how this is an impossible task given my many delightful qualities. Let’s list them…) Cancer requires that I stumble around in the debris of dreams I thought I was entitled to and plans I didn’t realize I had made.

But cancer has also ushered in new ways of being alive. Even when I am this distant from Canadian family and friends, everything feels as if it is painted in bright colors. In my vulnerability, I am seeing my world without the Instagrammed filter of breezy certainties and perfectible moments. I can’t help noticing the brittleness of the walls that keep most people fed, sheltered and whole. I find myself returning to the same thoughts again and again: Life is so beautiful. Life is so hard.

In thinking back on the sermon from yesterday, Christ’s answer to the world of conditional thinking is always declarative. Christianity’s core message is never delivered from the future-tense conditionality of an “if…then…” incentive, but through the past-tense (and passive) gift that was already given on our behalf. That past-tense gift has present-tense consolation. The cross demonstrates God’s presence in the absence of answers. Christian hope, therefore, does not look at suffering–or our handling of our suffering–as a prooftext for our salvation, but looks instead to the cross, to the God who suffered on it, and the God who, from it, said (declaratively): “It is finished.”

COMMENTS

13 responses to “The Prosperous Gospel of Stage 4 Cancer”

Leave a Reply

Choked up over here. A very Amen to this.

….Ditto

Amen

Kate Bowler’s (and the rest of this article) words are a gift. I will not forget them.

Thank you!

This. Thank you. Nothing in my hands I bring. Simply to thy cross I cling

This and the Bowler article both humbled me and reminded me I am but dust–beloved, beloved dust.

Yes. Truth. The distortion of faith in my faith (prosperity gospel) is guilt and confusion when we most need to fall into the arms of our Loving Lord and allow Him to carry us.

When I read about “finding new ways to be alive”, being older, I was reminded of Anne Sexton’s “Courage”:

Later,

when you face old age and its natural conclusion

your courage will still be shown in the little ways,

each Spring will be a sword you’ll sharpen,

those you love will live in a fever of love,

and you’ll bargain with the calendar

and at the last moment

when death opens the back door,

you’ll put on your carpet slippers

and stride out.

Anne Sexton

from Courage

in The Awful Rowing After God