The American justice and penal systems may be hot topics today, but it isn’t the only reason that Bryan Stevenson’s Just Mercy became a New York Times bestseller in 2014. As the founder of the Equal Justice Initiative he’s certainly earned his room to speak about oppressive justice and the death penalty and mass incarceration. But he is also compelling as a storyteller—he is not simply interested in the facts and figures justifying prison reform. He is also intertwined in individual lives of prisoners; their stories play a huge role in his own coming-of-age.

The American justice and penal systems may be hot topics today, but it isn’t the only reason that Bryan Stevenson’s Just Mercy became a New York Times bestseller in 2014. As the founder of the Equal Justice Initiative he’s certainly earned his room to speak about oppressive justice and the death penalty and mass incarceration. But he is also compelling as a storyteller—he is not simply interested in the facts and figures justifying prison reform. He is also intertwined in individual lives of prisoners; their stories play a huge role in his own coming-of-age.

If you’re unfamiliar with the book, Just Mercy is the memoir of a young, ambitious defense lawyer who becomes transformed by the cases that came his way when he founded his practice. Not only does Stevenson’s understanding of the criminal justice system grow more complicated, his own understanding of himself does, too.

In the American political-social arena, it seems increasingly easy to boil down social justice issues with deified victims and hard-won solutions. It’s why reading about them, at least to me, feels tiresome. Victim-Oppressor lines are drawn in binaries, and their resolutions are figured to be no less complicated. But Stevenson points to the deeper-rooted problem—deeper than the issues of the day and the systems that provoke them.

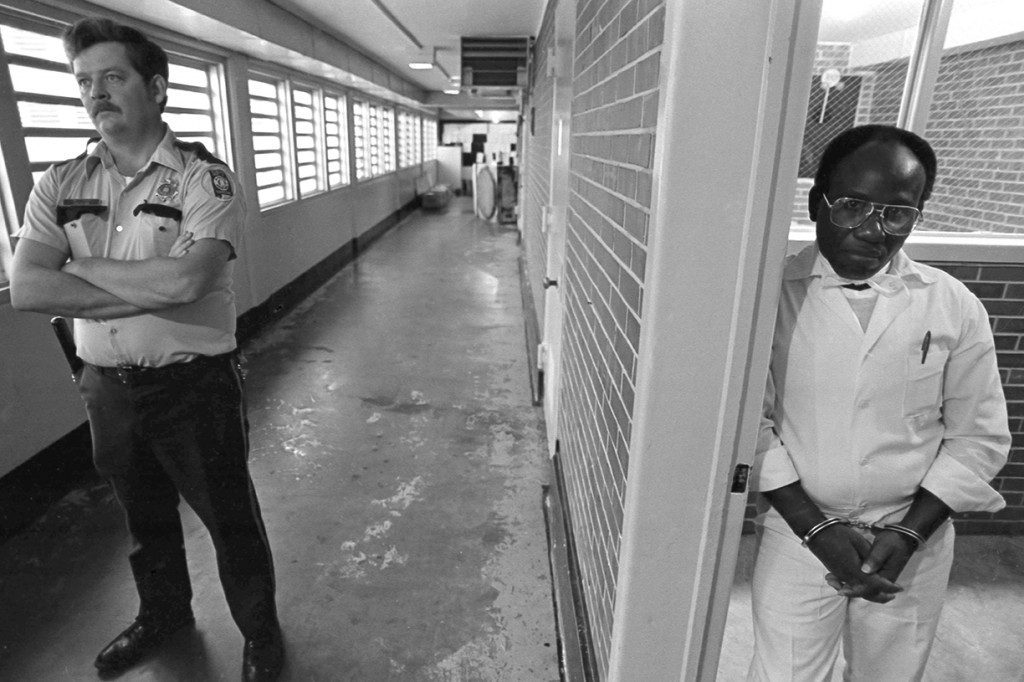

In one of the last chapters, entitled “Broken,” Stevenson tells the story of Jimmy Dill, a convicted murderer who had been scheduled for execution in the state of Alabama. Stevenson’s staff took on the case in the last 30 days of Dill’s life because Dill not only suffered from an intellectual disability, but his conviction had been based on suspect evidence that Stevenson’s team believed to be erroneous. Had Dill been able to afford a lawyer the first time, he wouldn’t be on death row. As it happened, though, nothing could be done. In the last hour, Dill called Stevenson to say thank you for trying.

What Stevenson realizes, in the misery of this failure, are not just the external factors prohibiting redemption, but the internal factors every human lives with. The yearning, in one way or another, to put away the inner-criminal. In this moment, a turning point for Stevenson, he comes to grips with the need to recognize common brokenness. Only in doing so would one seek to surpass the shortcomings of quid-pro-quo—the justice of the human world—and see the need for something outside it—mercy.

When I hung up the phone that night I had a wet face and a broken heart. The lack of compassion I witnessed every day had finally exhausted me. I looked around my crowded office, at the stacks of records and papers, each pile filled with tragic stories, and I suddenly didn’t want to be surrounded by all this anguish and misery. As I sat there, I thought myself a fool for having tried to fix situations that were so fatally broken.

For the first time I realized that my life was just full of brokenness. I worked in a broken system of justice. My clients were broken by mental illness, poverty, and racism. They were torn apart by disease, drugs and alcohol, pride, fear, and anger…In their broken state, they were judged and condemned by people whose commitment to fairness had been broken by cynicism, hopelessness, and prejudice.

I looked at my computer and at the calendar on the wall. I looked again around my office at the stacks of files. I saw the list of our staff, which had grown to nearly forty people. And before I knew it, I was talking to myself aloud, “I can just leave. Why am I doing this?”

It took me a while to sort it out, but I realized something sitting there while Jimmy Dill was being killed at Holman prison. After working for more than twenty-five years, I understood that I don’t do what I do because it’s required or necessary or important. I don’t do it because I have no choice.

I do what I do because I’m broken, too.

My years of struggling against inequality, abusive power, poverty, oppression, and injustice had finally revealed something to me about myself. Being close to suffering, death, executions, and cruel punishments didn’t just illuminate the brokenness of others; in a moment of anguish and heartbreak, it also exposed my own brokenness. You can’t effectively fight abusive power, poverty, inequality, illness, oppression, or injustice and not be broken by it.

We are all broken by something. We have all hurt someone and have been hurt. We all share the condition of brokenness…I desperately wanted mercy for Jimmy Dill and would have done anything to create justice for him, but I couldn’t pretend that his struggle was disconnected from my own. The ways in which I have been hurt—and have hurt others—are different from the ways Jimmy Dill suffered and caused suffering. But our shared brokenness connected us.

…I thought of the guards strapping Jimmy Dill to the gurney that very hour. I thought of the people who would cheer his death and see it as some kind of victory. I realized they were broken people, too, even if they would never admit it. So many of us have become afraid and angry. We’ve become so fearful and vengeful that we’ve thrown away children, discarded the disabled, and sanctioned the imprisonment of the sick and the weak—not because they are a threat to public safety or beyond rehabilitation but because we think it makes us seem tough, less broken. I thought of the victims of violent crime and the survivors of murdered loved ones, and how we’ve pressured them to recycle their pain and anguish and give it back to the offenders we prosecute. I thought of the many ways we’ve legalized vengeful and cruel punishments, how we’ve allowed our victimization to justify the victimization of others. We’ve submitted to the harsh instinct to crush those among us whose brokenness is most visible.

But simply punishing the broken—walking away from them or hiding them from sight—only ensures that they remain broken and we do, too. There is no wholeness outside of our reciprocal humanity.

COMMENTS

2 responses to “No Wholeness Outside Our Reciprocal Humanity”

Leave a Reply

Holy cow. This gives me the shivers. It puts my feelings of the week into words I haven’t been able to conjure or communicate. Thank you for this, Ethan! I’d love to link this to my MaM article somehow.

YES! This book is great! Thanks for writing about it, E!