As we blanket our house with nic-nacs and expensive toys, it’s the perfect time to look back at the things that matter—or the things that mattered—or the things that at least we thought mattered at the time—to us this year. Here are Five Golden Themes for 2015—repeated stories and obsessions that didn’t just creep into the collective cultural psyche, but seemed to define it, for better or worse.

Performancism and Suicide. I had to check and make sure this hadn’t been on one of our previous year-end roundups. I thought surely, with all  the times we’ve written about “the epidemic,” this is not such a recent phenomenon. And it’s not. But the coverage has exploded in the last twelve months, especially in its connection with student perfectionism and “clusters” of high achievement. Culturally speaking, the concurrence of the two in places like Palo Alto, CA is shocking. Why would a demographic of such promise and potential fortune struggle to find hope? What’s wrong with this picture?

the times we’ve written about “the epidemic,” this is not such a recent phenomenon. And it’s not. But the coverage has exploded in the last twelve months, especially in its connection with student perfectionism and “clusters” of high achievement. Culturally speaking, the concurrence of the two in places like Palo Alto, CA is shocking. Why would a demographic of such promise and potential fortune struggle to find hope? What’s wrong with this picture?

This has certainly given us pause, and has made room for books this year like Deresiewicz and Lythcott-Haims. For us at Mockingbird, though, it is the boiling point of a tension we speak of all too often. The connection between mental illness and meritocracies is the contemporary face of a deeper issue about a deeper sense of belonging—namely the distinction between “Law” and “Grace.” We even wrote a book about it this year. But the same questions come from it: Why is the justification/earning/achieving game never enough? And is there a justification that could never be taken away?

From Mockingbird: “Simultaneously Frazzled and Fragile: Surviving a Culture of Overachievement” by David Zahl

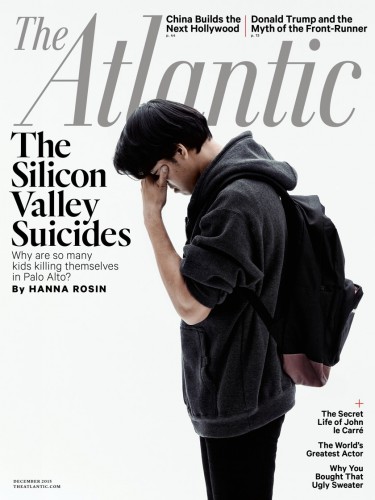

At-Large: “The Silicon Valley Suicides,” by Hanna Rosin in The Atlantic and Frank Bruni’s “Best, Brightest–and Saddest?” in The New York Times

At the Bookstore: How to Raise an Adult by Julie Lythcott-Haims and Excellent Sheep by William Deresiewicz

Disembodiment. One thing that is hard about writing a year-end roundup like this, especially when it is thematic like this one is, is that the themes feel much more related when compiled. It’s not just because we put together a Technology Issue this year—all of today’s issues and neuroses seem bolstered by our devices. Which made our tech issue timely, but it also meant that words like “disembodiment” got thrown around a lot. What happens when our minds (and souls) are detached from the bodies they live in? What does it look like to live in a world that is, by and large, living elsewhere. It’s a giveaway that our Tech Issue opened with the sage words of Seneca, “To be everywhere is to be nowhere.”

Our (much missed) comrade Will McDavid did a series on the philosophies of disembodiment, how knowing can and can’t be objective and purely scientific. This creates all kinds of problems when we think about religion and the Bible, and especially, a God who became a man—embodied—and walked amongst us. But, in more everyday terms, we also see where our boundless mental/technological access can get us into some serious interpersonal trouble. This phenomenon surfaces in every category, from pornography and dating to internet shaming and victim witchhunts.

From Mockingbird: The Disembodied Truth Series by Will McDavid and

“Tinder, Porn, and the Dying Art of Falling in Love” by Ethan Richardson

At-Large: “A New Theory of Distraction” by Joshua Rothman, The New Yorker

At the Bookstore: Modern Romance by Aziz Ansari and Eric Klinenberg, and Matthew Crawford’s The World Beyond your Head.

Fear. Fear of failure. Fear of missing out. Fear of “falling leaves.” No word better describes our united front to ISIS, national privacy, or the future of dating relationships than the word “fear.” And no one does a better job talking about it than Marilynne Robinson did in the New York Review of Books just a couple months ago. I have to quote her:

There are always real dangers in the world, sufficient to their day. Fearfulness obscures the distinction between real threat on one hand and on the other the terrors that beset those who see threat everywhere. It is clear enough, to an objective viewer at least, with whom one would choose to share a crisis, whose judgment should be trusted when sound judgment is most needed.

Granting the perils of the world, it is potentially a very costly indulgence to fear indiscriminately, and to try to stimulate fear in others, just for the excitement of it, or because to do so channels anxiety or loneliness or prejudice or resentment into an emotion that can seem to those who indulge it like shrewdness or courage or patriotism. But no one seems to have an unkind word to say about fear these days, un-Christian as it surely is.

It is probably safe to say that “Fear” is the underlying emotion of the year—not to mention the basis of all these themes. Fear as “un-Christian” was certainly an offense to me, as is Jesus’ rebuke to his followers not to worry. Worry we will, though, and in a time when such worry is not just warranted but pedestaled, the good news rings ever more radically as an antidote to our indulgence.

From Mockingbird: “Mary Karr Asks What We’d Write If We Weren’t Afraid” by David Zahl, and “21 Beheaded Egyptians Make Me Proud to Be A Christian” by R-J Heijmen

At the Bookstore: “The Givenness of Things” by Marilynne Robinson

Political Correctness, Microaggressions and Trigger Warnings. Hardly news, but 2015 will most memorably be defined by the fury of “victims” that took the stage in the public sphere. Whether it was Cecil the Lion, collegiate job security, or redescriptions of gender profiles, some have called this the height of the “post-critical age,” where offenses of language and emotional demeanor (micro-aggressions) are as accountable (and punitive!) as a state courtroom. Except that they’re everywhere, sitting on every desktop. Sociologist Jonathan Haidt described it as “vindictive protectiveness,” not just about the letter of the law, but about the emotional security of any student/reader/viewer who might be offended.

The effect, as we’ve detailed numerous times, is telling in a couple ways. First, much as we may culturally pine for a post-religious, post-absolutist society, we still very much adhere to the justification of victims, and the vindication of a wrongdoer. Our swelling anger at injustice—as we saw during the Cecil the Lion debacle—betrays an underlying thrill at being wronged.

This isn’t just about internet outrage, though. It’s also about the kind of truth-telling that gets smothered because of this non-offensive groupthink. When a society’s moral vision is only as high as emotional palatability, you not only get a “hero” like Donald Trump—you are also forever safe from the offensive news (about ourselves) we’ve shielded ourselves from hearing.

On Mockingbird: “Are You Washed in the Blood of the Lion?” by David Zahl and The Trigger-Warning Life by Todd Brewer

At-Large: “The Coddling of the American Mind” at The Atlantic, by Jonathan Haidt, and “The Crisis of Character,” at Spiked Review, by Brendan O’Neill

Stephen Colbert. Can’t we end on an up-note? Please? It’s Christmas! Is there any hope from the above? Well, no. Not from them. But there is Stephen Colbert. Many wondered what in the world Colbert’s new venture into late night would involve, and we haven’t been disappointed. There isn’t much more to say beyond the fact that Stephen’s profound late-night levity, in the face of such national worry and cultural animosity, is more than sheer comedy—it’s joy, which Stephen calls the “infallible proof of the existence of God.” In the three short months that the show’s been on, I’m at least happy that there isn’t such a huge diversion from the Colbert we knew from the Report. Amid the cornball tropes we’re used to with modern late-night, we have seen a late-night host that is doing more than just providing gags (though those are there, too). He is asking tough questions and having awkward interviews, but he’s never intimidated or aggressive. He sees hope in the darkness, and is having fun while he’s at it. In the midst of his new show, we have certainly gotten to see the man behind the character.

On Mockingbird: “Colbert and Biden: Faith Sees Best in the Dark” by Sarah Condon

At-Large: “The Late, Great Stephen Colbert,” GQ Magazine

Notable on the show: Stephen’s Interview with Bill Maher, Donald Trump, Joe Biden

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply