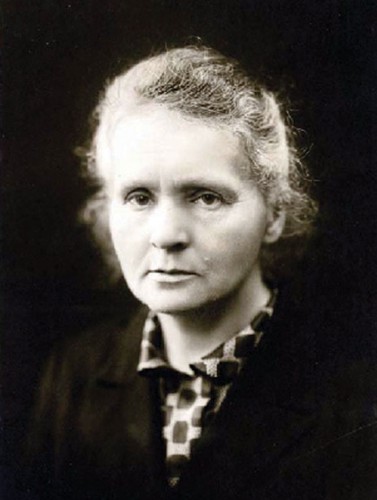

In the film adaptation of Wild, Cheryl Strayed (played by Reese Witherspoon) reads the final stanza of “Power,” a poem by Adrienne Rich, on her first night hiking the Pacific Crest Trail.

She died a famous woman denying

her wounds

denying

her wounds came from the same source as her power

These words, referring to scientist Marie Curie, strike a chord with Strayed when she reads them, and they stayed with me as well. They became the lens through which I found myself making sense of this remarkable story.

Unfortunately, I can only discuss Wild from the perspective of the film, which is based closely on the best-selling memoir. A year after its release I’m a little behind the hype, but there’s no accounting for timing. If you’ve experienced Cheryl Strayed’s story in any form, then you probably understand why I couldn’t help but write about it anyway. On a micro level, the themes in Wild – death, failure, recovery, life – are terribly familiar. It’s a story about me. On a macro level, Wild is about all of us: humanity, fallen long ago, in dramatic need of redemption.

Here’s the long and short of it: When Cheryl was a senior in college, her mother, who was “the love of her life,” died abruptly and traumatically of lung cancer. She was just 45. Cheryl goes off the deep end, denying her wounds: she takes up heroin and seriously promiscuous sexual behavior (all while married). She eventually divorces her husband and gets pregnant with another man’s baby. In that moment, facing motherhood in these circumstances, she sees how far she’s come from the woman her own mother believed she could be. By chance, Cheryl spots a book about the Pacific Crest Trail, and decides to hike it in hopes of recovering some of her lost and fallen self; maybe in the crushing solitude of the wilderness, she can finally find the space to grieve.

The first shot of any well-made movie is critical. It sets the stage for the rest of the narrative. Wild begins abruptly with a panoramic view of the great outdoors, and the protagonist panting in exhaustion off camera. She groans in pain – like Eve, long-suffering in her tiresome passage this side of paradise.

Cheryl sits down to take off her boots – her feet are blistered and bleeding. As she sighs in relief, one of her boots tumbles down the side of the mountain, lost forever. Her boots are critical. In fury and resignation, Cheryl hurls the other one off the mountain along with it, yelling to no one, “F*CK YOU, BITCH!” and then screams a wild and desolate scream.

The movie begins at what appears to be the worst of Cheryl’s hike, and then takes us back to the first trailhead in the Mojave Desert. We find out later why losing her boot was more significant than just a means of her survival. The “bitch” at whom Cheryl screamed was a nurse at the hospital where her mom spent her final days. Cheryl’s brother had gone off radar in effort to hide from the fact that his mom was dying. When Cheryl finally finds him, they return to the hospital to a sign on the door of their mother’s room: “Please check in at nurse’s station before entering.” The nurse sees them approaching and says, “We put ice on her eyes.” “What?” says Cheryl, confused. “She wanted to donate her corneas, so we…”

She had died an hour before they got there. The doctors said she had a year to live, but she passed away just one month after her diagnosis.

Cheryl’s mother, Bobbi, was the center of her world. After leaving their alcoholic and abusive father, Bobbi basically raised her children alone, and did so with gusto and joy. Cheryl wonders along the trail if her mom was merely denying her wounds. She waitressed full-time to support Cheryl and her brother, and finally went to college the same year as Cheryl. Bobbi is the picture of woman – in all of our historical struggle and glory. Her character parallels the scientist Marie Curie. Curie was also a single mother, who overcame incredible odds to achieve all that she did as a woman in her time. She died at 66 of aplastic anemia, brought on by exposure to radiation during her research. She must have known. But Curie’s research led to the successful treatment of cancer. What if she had stopped what she was doing because she suspected it was making her ill? Denying her wounds came from the same source as her power. Cheryl recalls a time when Bobbi spoke of a similar sentiment. She said she didn’t regret a thing. Every experience, both good and bad, made her who she was – a mother to Cheryl and her brother.

Cheryl’s mother, Bobbi, was the center of her world. After leaving their alcoholic and abusive father, Bobbi basically raised her children alone, and did so with gusto and joy. Cheryl wonders along the trail if her mom was merely denying her wounds. She waitressed full-time to support Cheryl and her brother, and finally went to college the same year as Cheryl. Bobbi is the picture of woman – in all of our historical struggle and glory. Her character parallels the scientist Marie Curie. Curie was also a single mother, who overcame incredible odds to achieve all that she did as a woman in her time. She died at 66 of aplastic anemia, brought on by exposure to radiation during her research. She must have known. But Curie’s research led to the successful treatment of cancer. What if she had stopped what she was doing because she suspected it was making her ill? Denying her wounds came from the same source as her power. Cheryl recalls a time when Bobbi spoke of a similar sentiment. She said she didn’t regret a thing. Every experience, both good and bad, made her who she was – a mother to Cheryl and her brother.

The wilderness is a frequent Biblical backdrop; the Israelites wandered through it for 40 years. Jesus went there to be tempted by the devil. In the wilderness – at our most barren, needy, and vulnerable – is where miracles and manna abound, or maybe we’re just more aware of them there. Cheryl encounters all manner of manna on the PCT. People who offer her uncharacteristic guidance and good-will. A sign-post at just the right moment. Water. New boots. The trail, even at its harshest, always seems to open up before her – as if the way through, while tough to the point of nearly giving up, has already been meticulously prepared.

Though painstaking at times, Cheryl faces her wounds head-on, rather than denying them. She begins her 1,100-mile journey wearing a pack so huge and burdensome, fellow hikers dub it “the monster.” Metaphorically, the further she gets along the trail she learns which items she really needs, versus the dead weight. Her load, both literal and figurative, begins to wither.

In one of the last scenes in the movie, she comes across a little boy walking with his grandmother and their llama, named Shooting Star. The boy tells her he has problems that he isn’t supposed to talk about. She says she has problems too, “But, you know, problems don’t stay problems. They turn into something else.” And then he sings her a song his mother taught him. While he sings, memories of Cheryl’s mom flash through her mind; she’s finally beginning to say goodbye:

From this valley they say you are leaving

We shall miss you bright eyes and sweet smile

For you take with you all of the sunshine

And it brightened our pathway a while…

As the boy and his grandmother walk away, Cheryl drops to the ground and weeps. It takes a little boy and a shooting star to bring her to her fragile knees. She looks to the sky and says, “I miss you. God I miss you.” And then she makes her way to her ultimate destination: the boarder of Oregon and Washington, the Bridge of the Gods. On the last glad leg of her long, 94-day trek through the woods, the camera hangs on a statue of a cross while Cheryl says in a voiceover:

“There’s no way to know what makes one thing happen and not another. What leads to what. What destroys what. What causes what to flourish, or die, or take another course. What if I forgave myself? What if I was sorry, but if I could go back in time I wouldn’t do a single thing differently? What if I wanted to sleep with every single one of those men? What if heroin taught me something? What if all those things I did were the things that got me here? What if I was never redeemed? What if I already was?”

Right in Eden, when sin and suffering entered the world, God had already set into motion the instrument of His salvation. It wasn’t a last-minute Hail Mary for the win. We see in hundreds of prophecies throughout history in the Old Testament that God had always known – down to the hammer and nail, so to speak – the exact and precise design for our deliverance. What if we were never redeemed? What if we already were.

In the process of divorcing her first husband, Cheryl changes her last name to “Strayed.” “It’s Strayed, like a dog,” she explains, and there’s a quick shot of a dictionary page: “…to wander from the proper path, to be lost, to be without a mother and father, to become wild.” We read in Isaiah 53, foretelling of Jesus that “We all, like sheep, have gone astray, each of us has turned to his own way, and the Lord has laid on him the iniquity of us all.” This is good tidings of the greatest joy. It is cause for the desert and the parched land to be glad, for the wilderness to rejoice and blossom. We are, every last one of us, strays. Accepted or denied we have deep, punishing wounds. But because of Jesus on the cross, problems don’t stay problems. “The punishment that brought us peace was upon him, and by his wounds we are healed.”

While standing on the Bridge of the Gods, Cheryl’s voiceover continues:

“I knew only that I didn’t need to reach with my bare hands anymore…My life – like all lives – mysterious, irrevocable, and sacred, so very close, so very present, so very belonging to me, and how wild it was to let it be.”

COMMENTS

2 responses to “A Voice of One Calling In The Wilderness: The Source of Power in Wild”

Leave a Reply

Thank you for writing a piece about Wild. Soon after I watched the movie on DVD last week, I went to the Mbird site to see if someone spoke about it. And lo and behold, you did. Good movie. Those last few verses of the movie did me in. Sweet Niagra Falls falling through my eyes like bitter hope. You know, I cried. I could have just said that…

Great film doesn’t cut it.

Brings and takes me places.

Leaves me wandering…