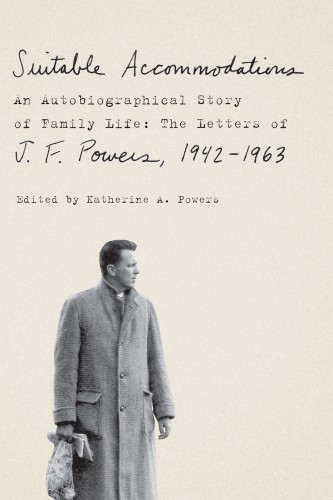

In a review of J.F. Powers’ book of letters, Adam Gopnik of the New Yorker refers to the mid-century writer as a Catholic cross between Chekhov and Garrison Keillor. Says Gopnik, “His tales had a Trollopean sensibility: he accepted the necessity of the divine institution, without unduly sanctifying its officials. Small rivalries (I recall one good story in which a priest with a valet engenders the envy of his colleagues) and little epiphanies (as in the beautiful ending of the story “Lions, Harts, Leaping Does,” in which a dying friar loses his pet canary in a snowstorm ) were his subjects.”

In a review of J.F. Powers’ book of letters, Adam Gopnik of the New Yorker refers to the mid-century writer as a Catholic cross between Chekhov and Garrison Keillor. Says Gopnik, “His tales had a Trollopean sensibility: he accepted the necessity of the divine institution, without unduly sanctifying its officials. Small rivalries (I recall one good story in which a priest with a valet engenders the envy of his colleagues) and little epiphanies (as in the beautiful ending of the story “Lions, Harts, Leaping Does,” in which a dying friar loses his pet canary in a snowstorm ) were his subjects.”

Garrison Keillor himself describes Powers as “a great old Irish master who God plopped down in Minnesota as a joke.”

I didn’t know anything about Powers, but now I want to read everything he ever wrote, after just finishing his final novel (he only wrote three), Wheat That Springeth Green. In the introduction to the version I have, his daughter Katherine Powers explains that her father had a real interest in the priestly vocation.

To many young men of his generation, the problem of a religious vocation boiled down to what one would have to give up…But to a man like my father, the real problem seemed less giving things up than taking them on: taking on people, specifically.

This is the problem faced by Joe Hackett, a track-and-field all-star who decides to become a priest. But not just any priest. Hackett longs for the tribulation (and tributes!) of sainthood. As a young seminarian, he quotes extensively from the early church mystics and martyrs. He longs to be like all those contemplatives of old, with knees callused and scabbed from prayer. He sincerely covets the hairshirt the seminary’s Rector displays in his office (as a joke), and he forms a small group of other seminarians serious about personal sanctity. He continues to tell them, Rooney and Mooney that, as a priest, “You can’t give what you haven’t got.” Slowly, his little band of monastics begin to bail.

Joe told Mooney, and quoted Pope Pius XI: “ ‘Sanctity is the chief and most important endowment of the Catholic priest,’ Chuck. ‘Without it other gifts will not go far; with it, even supposing other gifts to be meager [Joe’s italics], the priest can work Marvels.’” Joe prescribed more prayer and renunciation for Mooney. “I saw a Baby Ruth wrapper in your wastebasket, Chuck.”

At this point in Joe’s career, this is the “priestly fellowship,” the continual and earnest (and competitive) prodding for growth amongst one’s contemporaries. Joe’s own saintly endurance begins to wane too, though, as the work takes precedence over his own ideas. Coming on as a curate in his first job, his prayer time is deeply cut into by the demands of the parish. He judges his superior, Father Van Slaag, for leaving him with the heavy load of pastoral work, while he spent nearly all his time in prayer, getting his scabby knees. In the end, Joe’s mental health is better off for it.

At this point in Joe’s career, this is the “priestly fellowship,” the continual and earnest (and competitive) prodding for growth amongst one’s contemporaries. Joe’s own saintly endurance begins to wane too, though, as the work takes precedence over his own ideas. Coming on as a curate in his first job, his prayer time is deeply cut into by the demands of the parish. He judges his superior, Father Van Slaag, for leaving him with the heavy load of pastoral work, while he spent nearly all his time in prayer, getting his scabby knees. In the end, Joe’s mental health is better off for it.

But the best times for Joe were those times when he could be of real use to people as a priest—those times of trial, tragedy, and ordinary death—into which he entered deeper than he had before. “After years of trying to walk on the water, you know…it’s good to come ashore and feel the warm sand between my toes.”

Joe finally lands a parish of his own, though it is not the one he’s imagined. A suburban community called Inglenook, with an enormous discount department store, The Great Badger. It is not sexy, and neither are the parishioners. Disappointed by the absence of anybody who could be considered “the least of these,” he moves a poor, urban family into a home in the neighborhood, just to afflict the comfortable. It backfires on him, though. The family is mostly thankless; they stop coming to church and, instead, he must accept the suburbanite parish he’s been given. He develops a heavy drinking (and baseball) habit to cope.

A new, bright-eyed curate is assigned to Joe’s parish named Bill, a green seminary grad. Bill and Joe become comrades in a new kind of “priestly fellowship,” the losing kind. Joe becomes Bill’s guide into a more realistic sense of the calling of the priesthood. More than personal sanctity, more than transformation, Joe began to see the light of the priesthood in a more subdued sense of presence in weakness. The otherworldly world of miraculous prayers and mystics is not his world anymore.

One night, speaking of his first appointment, he was at pains to present Van as someone in a great tradition of the Church and not as some kind of nut, as Bill appeared to think when told of Van’s horny knees. “He was trying to go all the way, Bill, and still is, I guess. I was like that myself—just a tenderfoot, though—when I went to Holy Faith. But I soon woke up, or gave up, however you look at it.

What happened to your hair shirt?

I buried it.

Joe, where do you stand on all that now?

I’m sitting down.

That’s how you look at it?

Yes, because that’s how it is.

Formidable surrender for Joe who, for so long, has stood by the rarified power of a priest’s spirituality. It comes at a time when the Archdiocese is requiring his parish to bring in more money than they can possibly provide. His job, a thankless presence among demanding people, now demands something new: to make demands from them. He and Bill can’t do it. No one wants to give and everyone has an excuse. Because he will not stoop to fund-raising campaigns, he begins gambling with bookies to try to cover the expenses. And drinking more. Bill drinks more, too. The second half of the book is mostly Joe and Bill, coming home after knocking on doors to no avail. This, the reader finds, is the light-hearted sobriety of the vocation. You will not change much.

When they returned to the rectory, though, their evenings out, fruitless for Bill and nearly so for Joe, became something else—the best nights yet for priestly fellowship. Joe, if he returned first, as he usually did, would hand Bill a drink (“How’d it go?” — “Still batting zero”), and Bill, if he returned first, now followed that practice (“How’d it go?” — “Lousé”). Bill hadn’t had occasion to make the drinks before, with Joe there, and need not have followed his example, but did.

There is a deep-seeded understanding of the theology of the cross in Powers’ development of their priestly relationship, as well as their own ministry. Well-acquainted with the losing way, their success is called more to the heart of the ministry than to the totems of success. In other words, they don’t care about the money. They care about the parish. They are, as Katherine Powers notes, unlikely saints, doing their share to “eat like a horse” and “sleep like a log,” and leaving God to the bookkeeping.

Yet, in spite of everything, he did not despair. He possessed what G.K. Chesterton called “Christian optimism,” a paradoxical optimism “based on the fact that we do not fit in the world,” that every awful thing, every dismal victory of the moronic and specious, is just another confirmation that what happens under the sun is not reality, that we have here, as he took satisfaction in saying, no lasting home. In a contrarian assertion of hope, he transformed the dreck of modern existence, in which we are all bogged down, into a medium out of which springs beauty and new life. This is the view projected in Wheat That Springeth Green: “As for feeling thwarted and useless,” Joe, the novel’s uncomfortable hero, reflects, “he knew what it meant. It meant that he was in touch with reality.”

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply