I didn’t ask to become inane; it just happened one day while I was driving down the highway, trying to take a selfie while eating a burrito. (This was to stand in as a more interesting version of the “on my way” text.) Mercifully, the rice spilled on my dress, I realized what I was doing, and no one died on that stretch of I-64 that day.

Worlds away, a number of Russians haven’t been so lucky. After at least ten deaths by selfie this year alone, Russian police have launched a campaign for the “safe selfie” to get their youngest selfie-snapping generation to snap out of it. (See below for some unfortunate, reality-inspired examples of how Russian youth have met with substantive negative outcomes this year.)

Aside from the obvious question of why anyone would photograph themselves falling down a Ziggurat, the prohibition begs further inquiry into the nature of the trend. As it turns out, the drive to take extreme selfies isn’t limited to the children of the former Soviet Union; high-risk self-portraiture has also taken root in Spain, the UK, outer space, alligator swamps, and wherever else danger can be found.

In other words, what may have begun in one culture no longer belongs exclusively to it. The extreme selfie is spreading as something of an art form throughout the developed world. By “art form,” I don’t necessarily mean the selfie is the same kind of high art that belongs in the MoMA, but it’s surely a cultural expression definitive of our age, and something by which future generations will attempt to understand us. Further, it’s something by which the present generation is trying to understand itself, but often comes up short of anything but eye-rolling and frustration. (See last week’s most recent attempt in the Times op-ed “What Selfie Sticks Really Tell Us About Ourselves.”)

Selfie sticks and extreme selfies have more to tell us, however, than that we’re narcissistic or stupidly inclined to danger. They demonstrate a felt need to stuff more into our selfies as we curate their content to present ourselves to the world. Even where they aren’t necessarily “extreme,” we gravitate towards producing selfies that are at least interesting, because a human face is not enough. In particular, our face is not enough. While a mother may be perfectly content to take a picture of her child that’s no more than his face, and you may love a picture of your best friend or significant other in which he or she isn’t doing anything interesting, we desperately want the pictures we take and make of ourselves to be more than just us.

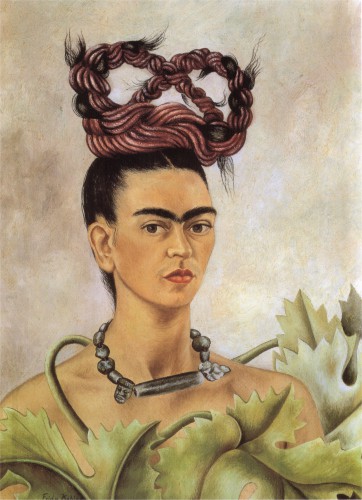

This is nothing new in the realm of self-portraiture. Take, for instance, Frida Kahlo, the majority of whose work consisted of them. (The same one who said, “I paint myself because I am so often alone and because I am the subject I know best.” Might today’s selfie-taker say the same?) What’s notable about Frida’s Fridas is that they’re almost never just Frida. They’re Frida with monkeys on her shoulders, or Frida with birds, or Frida clothed in leaves and with antler-braids frighteningly reminiscent of scenes from True Detective season one.

This is nothing new in the realm of self-portraiture. Take, for instance, Frida Kahlo, the majority of whose work consisted of them. (The same one who said, “I paint myself because I am so often alone and because I am the subject I know best.” Might today’s selfie-taker say the same?) What’s notable about Frida’s Fridas is that they’re almost never just Frida. They’re Frida with monkeys on her shoulders, or Frida with birds, or Frida clothed in leaves and with antler-braids frighteningly reminiscent of scenes from True Detective season one.

In other famous self-portraits, the artist is depicted with his easel or his work in the background, or else something to smoke. It’s the artist plus the artist’s cure, and this has everything to do with what art is in the first place. It seeks to do more than portray reality, which presents a unique challenge for the photographer, and an acute one for the self-photographer.

The theologian Emil Brunner, who was deeply interested in the relationship between art and faith, gives perhaps the most insight of all on the nature of the artistic drive (which I think is also applicable to the selfie phenomenon):

“Thus the origin of art does not lie in the perception of something which is present, but in an impulse to go beyond that which already exists. Art is always the child of the longing for something else. It shapes something which is not present, for and through the imagination, because that which is present does not satisfy man. In this sense it has more to do with Redemption than with Creation. It is an expression of the fact that man is conscious of his need for Redemption—otherwise how is it that he cannot be content with the world as it is? and it shows that he has a dim premonition and a vision of the possibility of a better world. It is, therefore, an indication, given with the created order, even to fallen man, of man’s knowledge of his origin, which he has never lost, of its restoration and its consummation.”

The extreme selfie—and really, most any selfie—is a kind of art in which we see the taker’s pained knowledge of her need for redemption. And perhaps more interestingly, the extra content of our selfies shows us what we think will save us, and even what we need saving from. For the daredevils in Russia, the climb to vertigo-inducing heights mocks death. For those who partook in the Selfie Olympics, cleverness defies a humdrum everyday existence. For many young women, the glamor shot with the perfect filter is leverage against the selves we know without makeup. And for many of us, whether we’re Ellen DeGeneres or a dude at a dinner party, the grinning group shot challenges our inwardly-felt sadness and loneliness.

For those belonging to Christ, the selfie may be fun, but it’s nothing to hold onto.

COMMENTS

4 responses to “The Extreme Selfie as an Art Form”

Leave a Reply

A very insightful essay, Kristen.

“High-risk self portraiture” is my new favorite phrase.

Lovin the Frida insight, and that Brunner quote gave me a lot to chew on! Thanks KGunn.

Beautifully written..