We live our lives bounded by those two mysteries, birth and death—our beginning and our end—and in between we stumble about in the dark, looking for the light, or at least for a good pair of existential shoes so we will not cut our feet quite so much on the sharp edges of Reality as we head for the Exit. What most of us find is ordinary life. The accidents of history have for now enclosed a space in which a wide swath of humanity—though not all of us, to be sure—experience ordinariness in the prosperity and pleasures of an industrialized and technologized world. With some effort, relative comfort and regular enjoyable experiences belong to us almost as a birthright. This is not necessarily bad. Go ahead, King Solomon said,

We live our lives bounded by those two mysteries, birth and death—our beginning and our end—and in between we stumble about in the dark, looking for the light, or at least for a good pair of existential shoes so we will not cut our feet quite so much on the sharp edges of Reality as we head for the Exit. What most of us find is ordinary life. The accidents of history have for now enclosed a space in which a wide swath of humanity—though not all of us, to be sure—experience ordinariness in the prosperity and pleasures of an industrialized and technologized world. With some effort, relative comfort and regular enjoyable experiences belong to us almost as a birthright. This is not necessarily bad. Go ahead, King Solomon said,

“Eat your food with gladness, and drink your wine with a joyful heart, for God has already approved what you do. Always be clothed in white, and always anoint your head with oil. Enjoy life with your wife, whom you love, all the days of this meaningless life that God has given you under the sun …” (Ecclesiastes 9:7-9).

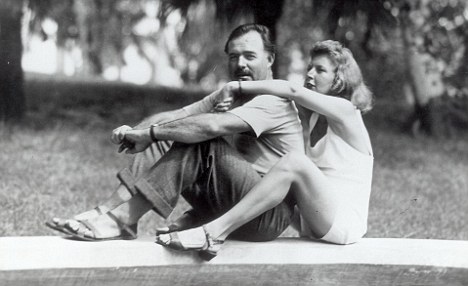

You might as well enjoy yourself. Work hard, eat, drink, dress well, and make love with your wife while you can, “for in the realm of the dead, where you are going, there is neither working nor planning nor knowledge nor wisdom” (Ecclesiastes 9:10). Is Solomon sincerely offering helpful advice here, or is he just being ironic, to make a point? Duane Garrett, a Southern Baptist Old Testament scholar, says that Solomon “anticipates the existentialists” in their perception of the absurdities of life. Indeed, he does. From Kierkegaard and Nietzsche to Camus and Sartre, from Dostoevsky to Hemingway, the existential philosophers and writers explored as best they could the realms of absurdity and death, as Solomon had thousands of years before. In the 20th century, the mystery of sex was added to the Existentialist mix. But Solomon had been there first, too.

Solomon wrote the two most indigestible books of the Bible, Song of Songs and Ecclesiastes. The former sings the delights of physical love between a man and a woman, replete with carnal metaphors and allusions—“your breasts are like two fawns.” The latter teaches that the course of this earthly life, shut up “under the sun,” is ultimately hebel—meaningless, futile, a chasing after the wind—since the prize and the glory for all who run the race is always the same—the silence of the grave. Sex and Death.

Sex, but Song of Songs is never tawdry or titillating. It is eros poetically restrained, a song of romantic love and consummation constrained within the boundaries of committed love and marriage. Constrained, yet still exuberant, and finally exultant: “Love is as strong as death, its passion intense as the grave. It burns like a blazing fire, like a mighty flame.” (Song of Songs 8:6). Yet even in the midst of celebration and the pledge that somehow love touches the eternal, comes the reminder that physical passion and intimacy, like everything else, is transitory; love may be strong but the grave is inexorable.

Death, but Ecclesiastes is never morbid or obsessive. It is down to earth reality, an unflinching look at the stamp of futility that death impresses on all merely earthly pursuits. Wealth, fame, ambition, achievement, pleasure; they never grant us immortality, they never gain eternity, they all blow away like dust in the wind. Who can argue with this logic? “Utterly meaningless! Everything is meaningless” (Ecclesiastes 1:2). And wisdom may be better than foolishness, but it still won’t stop time: “Like the fool, the wise man too must die!” (Ecclesiastes 2:16). Live long enough and life itself may lose its taste and turn to ashes in your mouth: “All things are wearisome, more than one can say. The eye is never satisfied with seeing, nor the ear with hearing.” Under the aspect of temporality everything eventually loses its shine: “There is nothing new under the sun.”

It’s certainly not Solomon’s fault, then, when the human race recycles the same game with each passing generation, expects different results, and yet is disappointed each time. Albert Camus, the French atheist existentialist, compared Man’s predicament to the Greek myth of Sisyphus, the man condemned by the gods to “ceaselessly rolling a rock to the top of a mountain, whence the stone would fall back of its own weight. They had thought with some reason that there is no more dreadful punishment than futile and hopeless labor.” Camus was right to make the comparison, but he was wrong to proclaim that this absurd labor can “take place in joy.” Maybe we can be happy for awhile; there is nothing wrong with enjoying the honest, innocent, and even passionate pleasures of our few days here on earth. But true joy? That’s not to be had “under the sun.” What’s the existential man, or woman, to do?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mpGDkO95KhI

The existential approach to life, like sexuality and high explosives, has the capacity to do damage if not constrained and channeled. Yet, equally, it can both strip away the overburden of the debris of ordinary life, revealing the bare bedrock of human existence, and also create the space—the possibility—of true encounter and real relationship. Taken wrong, the existential sensibility can seem little more than “eat, drink, and be merry for tomorrow we die.” Yet taken right, it can say “enjoy the journey when you can, but do not lose sight of the destination, and never forget that an accounting is inevitably due: ‘For God will bring every deed into judgment, including every hidden thing, whether it is good or evil’ (Ecclesiastes 12:14).”

I use the term “existentialism” only as a convenience; there is no such philosophical system as Existentialism. On the one hand, an existential frame of mind will cordially distrust any sealed-off, overly structured system of thought, be it Platonism, Calvinism, Marxism, or Veganism. On the other hand, however, the idiot sing-song, the mindless chant often rising from the postmodern landscape—“What’s true for you isn’t true for me”— bestirs both concerned compassion and disgust, something like a mother or father’s reaction to baby puke. No, the chastened, constrained existentialist says, there really is Truth, hard as it may be to find and acknowledge, and sometimes the truth hurts very much. There are hard edges to Reality, and they will not bend or soften to suit your wishes.

No sealed-off “foolproof” system is adequate to actual human living. No “airtight” theology survives contact with real existence. But any journey requires a map, even if it’s only a set of mental way-points, and from where we get our maps makes a difference as to where we end up. This is particularly clear in the life, writing, and death of Ernest Hemingway.

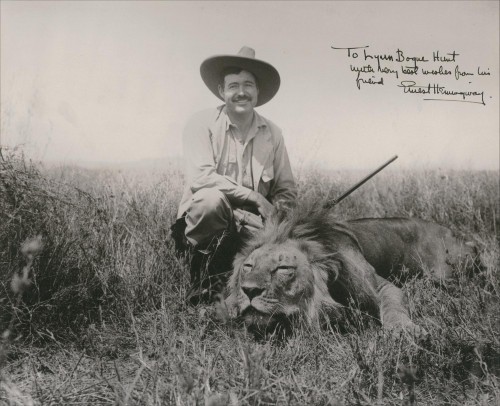

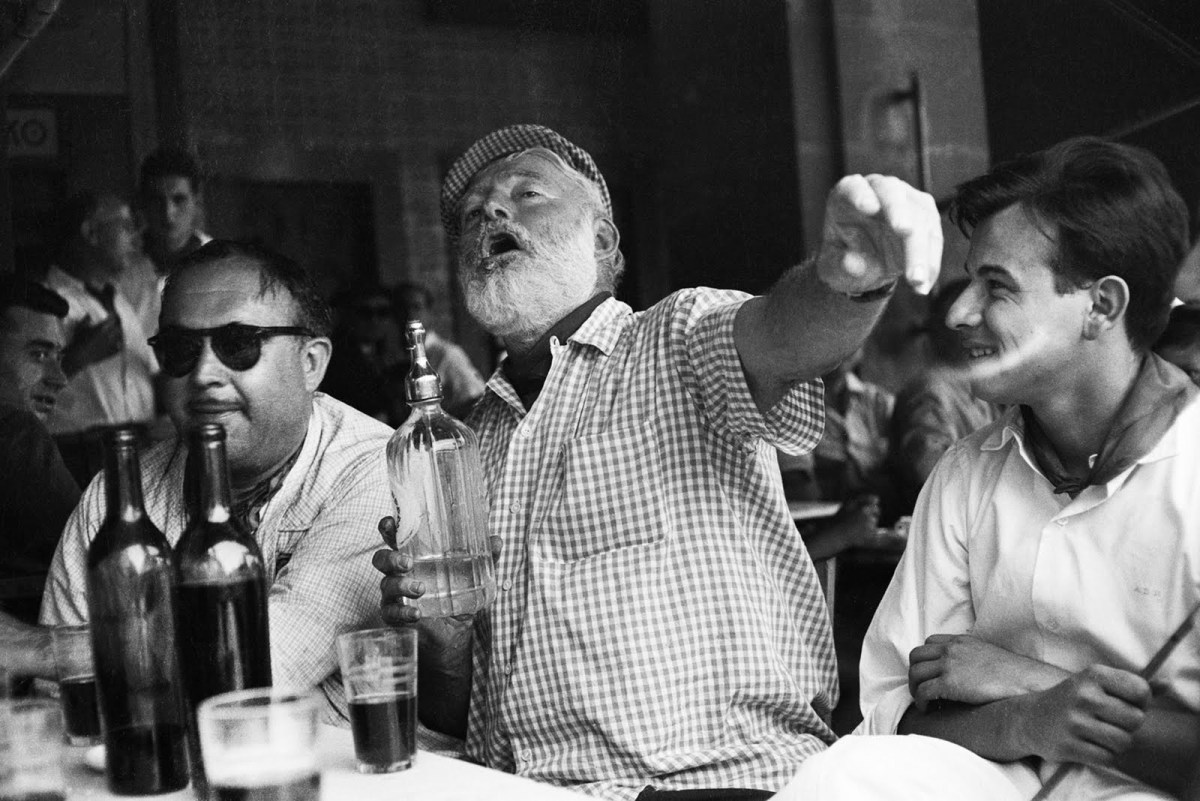

As Hemingway-biographer, Michael Reynolds wrote, “Hemingway was existential long before the word was current.” This was true of Hemingway’s life as well as his writing. In fact, it is impossible for anyone to be existential in writing without being existential in life. Hemingway’s pas de trois with sex and death is well-known, but the core of his existential effort, personal as well as literary, was the quest for grace. Every Hemingway code hero—Nick Adams, Jake Barnes, Frederic Henry, Robert Jordan, Harry Morgan, Thomas Hudson, the matadors of Death in the Afternoon, the old fisherman Santiago—sought “grace under pressure,” a phrase Hemingway himself coined. This grace was cool-headedness in the midst of violence and chaos, resolve in the face of inevitable loss and failure, and poise at the approach of death. This was the grace Hemingway himself sought all his life and never gained.

But this is manufactured “grace,” cobbled together of equal parts worked-up courage and personal ritual. It is hard individual effort, reliance on character, and aesthetic self-making. It is works. There is actually no grace in this “grace.” It is spiritual only in a vague, attenuated sense and religious only abstractly, as a purely personal, subjective sacrament. Hemingway’s spiritual and religious views were deeply ambivalent. To call him a Believer would empty that term of solid meaning, but to call him an Atheist is just propaganda. Grasping atheists are fond of the quote from A Farewell to Arms: “All thinking men are atheists.” But this is not Hemingway, nor even his alter ego, Frederic Henry. It is a major in the Italian Army speaking, not the main, or even a particularly sympathetic, character. Just as well, or better, to quote Jake Barnes in The Sun Also Rises, “I’m pretty religious,” and then call Hemingway a saint. What is true is that religion and the question of God never go away throughout the entire Hemingway oeuvre. To miss this is the same error as missing Melville’s struggle with his own Calvinist demons and thinking Moby Dick is just a tale about hunting a whale.

Hemingway wrote eloquently and stylishly about human struggle and failure, loss and death, relationships, love and, yes, sex. But he was a man profoundly disappointed with life, which included his disappointment with religion, and his disappointment with God. Of Hemingway’s discouragement with the failure of Catholicism in particular to provide him comfort or assuage his sense of guilt, Hemingway scholar Kenneth Lynn wrote, “he … adopted a privately formed and far more pessimistic religious vision which stressed that human life was hopeless, that God was indifferent, and that the cosmos was a vast machine meaninglessly rolling on into eternity.” At the last, Hemingway despaired and took his own life.

That almost sounds like something Qohelet—Solomon as the Teacher—might have felt, and wrote, and done at the end of Ecclesiastes. After a rambling, personal disquisition on the meaninglessness of all human endeavor and achievement; after finding no lasting satisfaction from wine, women, and song; after seeing that “time and chance happen to us all”; and that death, the final disappointment, takes everyone, shouldn’t Solomon have ended up in the same place as Hemingway? But he did not. Why not? Because Solomon had a different map, a map not of his own self- making, and not a personal code of manly grace under pressure. Solomon’s map allowed him to admit defeat without despair. The map, of course was Torah, the law and the commandments, and, most importantly in these circumstances, the instruction of the LORD, the covenant God of Israel.

making, and not a personal code of manly grace under pressure. Solomon’s map allowed him to admit defeat without despair. The map, of course was Torah, the law and the commandments, and, most importantly in these circumstances, the instruction of the LORD, the covenant God of Israel.

Hemingway’s existentialism failed him because it ended as it began, with the assumptions of an indifferent God in an indifferent universe, and the sufficienc of the self. Hemingway, as accomplished a man and writer as he was, patched his worldview together only from the broken pieces of a difficult youth, the disaffection and disenchantment of the post-World War I generation, and the deep themes of alienation and abandonment that had already overtaken modernist literature. Solomon, too, tried his hand at personal worldview making. He not only made himself, he made an empire. And when in hishubris he turned away from the LORD, the God of Israel, he lived long enough to hear God tell him, “Since this is your attitude . . . I will most certainly tear the kingdom away from you” (1 Kings 11:11).

Solomon’s existentialism showed him what Hemingway would also realize, that a man’s life “under the sun” is hebel—vapor—a chasing after the wind. But Solomon’s existential journey was also a return, to the God who alone gives meaning to life. I imagine, and I think it is consonant with Scripture, that Solomon wrote Ecclesiastes toward the end of his life. And I believe that, chastened and contrite, he was offering the broken pieces of his life back to God, who graciously accepted the offering. The last of Ecclesiastes is eloquently cautionary: “Remember your Creator while you are still young, before the days of despair come and the years draw near of which you will say, ‘I find no pleasure in any of this’ ” (Ecclesiastes 12:1); “Fear God and keep his commandments, for this is what being a man is all about” (Ecclesiastes 12:13). Maybe if Hemingway had listened to this he would have understood what true manhood is, and maybe he would have lived to find light beyond despair. Kenneth Lynn writes of Hemingway the art lover, that he was “deeply in love with the image of Jesus Christ crucified.” Perhaps even in his desolation, there was a part of Hemingway, deeply buried, that was in love with the real Jesus Christ crucified. Wouldn’t it be pretty to think so?

COMMENTS

4 responses to “Sex and Death: The Existentialism of King Solomon and Ernest Hemingway”

Leave a Reply

Dr. Nicholson is an outstanding writer and scholar I have had the pleasure to know personally. Thank you for promoting his work!

Rev. Jim Brock, M.Div., Psy. D.

Thanks, Jim! I’m glad you enjoyed the essay1

Wonderful article.