This post was co-written by Samantha McKean and Kristen Gunn. Sam is a student at Duke Divinity School, where she’s realizing what she actually does and doesn’t know. Kristen is heavily into words and why we say them, which is how this conversation became a post.

Sam: I say “I don’t know,” a lot. It’s a filler, a tic, the new “um” or “like” that your Com101 professors warned you about. It comes tacked onto the end of my sentences like sad parade banners. Most of the time, I don’t even notice I’m saying it.

I have a friend who always calls me out on it. She’ll stop me mid-rant and tell me firmly, “You do know.” And she’s right. The majority of the time I know what I’m talking about, or at least what I’m trying to say. The “I don’t know” is not an admission of ignorance; it’s something else.

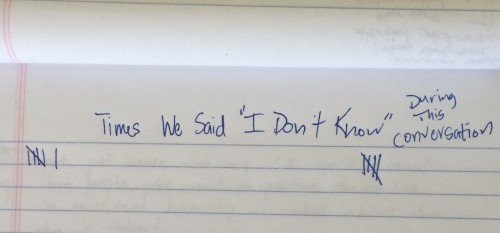

Recently Kristen and I were having a conversation when we noticed the trait in each other, I-don’t-knows sprinkled through our sentences like apologetic confetti. We stopped and talked about it. And since then, I’ve been noticing just how often the words come out of my mouth.

Kristen: Me too—and in what contexts it tends to happen. There’s real not knowing, and then there’s this other thing. People saying they don’t know and not actually meaning anything of the sort… I don’t know, I think it mostly happens when I’m slightly uncomfortable with what I’m saying, or with the person I’m saying it to. Or both.

Sam and I are two women from Texas and Ohio who had never met before this summer. That’s probably part of why we kept saying “I don’t know” so much during our early conversations. We didn’t know each other that well. We often knew what we were trying to say, but something about our unfamiliarity with each other in this context of a new friendship made us suddenly wobbly, suddenly unable to say what we really wanted to say.

At first, when we were chatting a few weeks back, we thought women were the only ones coughing and sneezing the “I don’t know” bug. But as we started sharing this idea with our friends, we noticed—and received free confessions from—a number of men who do this, too.

Sam: Right. People never fit into neat categories, but linguists and sociologists have noted that in general, men often talk to inform, while women’s speech is geared toward relating. Men will often speak more directly and assertively, use more declarative statements, interrupt more, change the subject more often, give advice more freely, and state their opinion more authoritatively. For women, on the other hand, the goal of conversation is to connect, and so a lot of effort is put into maintaining the other person’s feelings. They speak more tentatively. They front-load statements with qualifiers (“I could be totally wrong about this, but…”), use verbal hedges to lessen the force of their words (“kind of” and “maybe”), apologize more, interrupt less, and—yes—use phrases like “I don’t know” as involuntary fillers.

Of course, these trends are general and don’t apply to everyone. I know women who speak assertively and men who speak tentatively. The way we talk also depends on a lot of other factors, like geographical location (Midwesterners like me shape our speech more tentatively than frank New Englanders), who you’re talking to (I have little trouble speaking authoritatively to a four-year-old), and what you’re talking about (Pixar movies vs. politics, for instance).

Kristen: Yeah, I remember a lot of this from when I was a linguistics major in college. That was an interesting time. But if I could boil sociolinguistics down to anything, it would be this: we do what the cool kids do. We shape our speech after them, whether we’re relaters or asserters. And this is mostly because we’re always trying to do what linguists call “saving face.” Our “face” is our image of ourselves, and even in our speech we’re constantly seeking to keep a good one in front of others, whether this is ultimately geared towards being respected or being loved.

Sam: Yes. It’s about image-maintenance. The relationally-oriented “I don’t know” is less about a genuine concern for the others’ feelings, and more about a genuine concern for how others perceive me. It is a self-protective measure, an attempt to coat my conversation partner’s feelings toward me with a soothing glaze. It operates out of that fear of offending the other person. Because really, I’m just plain-old afraid that people won’t like me.

This fear has the power to distort what I’m really trying to say. The closer a topic of conversation gets to something I care about, the more I say “I don’t know.” The stronger my convictions, the more the phrase pops out. It’s a method of distancing myself from my opinion, a meek offering that tells others that they don’t have to take me seriously. The “I don’t know” takes my fiercest tiger of an idea and shrinks it into a kitten.

Kristen: Which is tragic, because you have some tigers in there. I so enjoy our conversations—that is, when we’re not both spewing the “I don’t know” all the time, trying so hard not to offend the other. Same with other friends! It’s the most fun talking to people when we’re able to be completely candid, not at all concerned with saving face.

Reminds me of my favorite part of Law and Gospel, the one that (I wonder why) keeps coming back to me:

“In the realm of the Law, we must keep face. In the realm of the Gospel, we can laugh at our own faces in the mirror. In the realm of the Law, we must tediously craft emails with the right balance of seriousness and brevity. In the realm of the Gospel, we’re free to say precisely the ridiculous thing that comes to mind, without fear of what brand of trouble our words may bring. While the Law incites us to point our fingers at others in blame, the Gospel provokes us to return the finger-pointing back to our own chest, and shrug our shoulders, and laugh at the absurdity.”

I don’t have to save my face if I can laugh at it!

Sam: And what’s funny about this fearless unselfconsciousness is that it actually lends so much more power to my words. When I’m not worried about how I’m perceived, I’m free to say precisely what I mean. I can strip the I-don’t-knows from my speech and sit comfortably with my bald-faced declarative statements, even if they’re unpopular or badly phrased—or even dead wrong. The Gospel frees me from that face-saving impulse to dull down my words, then loosens me up enough to hold them lightly.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply