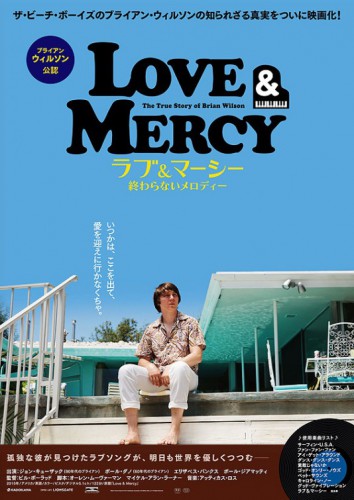

Saw Love & Mercy last night, and wow. As reviewers have been noting, it is not your average biopic, and certainly not much of a summer film, despite the source material. Which makes sense, I guess, since Brian Wilson is not your average bear. It has more in common with I’m Not There, than, say, Ray or Walk the Line, choosing as it does to focus on the two most dramatic periods of Brian’s life, his 1967 breakdown and his 1988 “comeback” (played by separate actors), rather than depict the full arc.

I’d read interviews where Brian himself decried the heaviness of the film, and you can see where he’s coming from. Love & Mercy does not shy away from the central irony of The Beach Boys, that the sunniest music in the world–indeed, music that still defines ‘sunniness’ 50 years later–came out of such a fractured and darkened situation. “Even the happy songs are sad”, observes the Mike Love character in reference to Pet Sounds, pretty much summing up Brian’s otherworldly appeal. (The inverse is often true in his music as well).

The film brought to mind my favorite section of the Beach Boys essay in A Mess of Help: From the Crucified Soul of Rock N’ Roll, which feels appropriate to share (should be available on Kindle next week!). But before I do, a few other notes on the film:

- The acting is truly exceptional. Paul Dano and John Cusack both hit it out of the park, each going far beyond impersonation, and Elizabeth Banks nearly steals the movie. Brett Davern as Carl was another highlight, Bill Camp as Murry was chilling, and the guy who plays Van Dyke Parks was uncanny. Only drawback may have been Paul Giamatti’s portrayal of Eugene Landy, which, while based in (sad) truth, still felt a bit, you know, Giamatti’d. Having him and Dano in the same movie was a gamble, as the two of them amount to a formidable stress-fest. Gratefully, they didn’t share any screentime.

- The structure works. As opposed to, say, Julie & Julia, to which it is being compared, neither ‘track’ overshadowed the other. Perhaps in the 80s portion, the romanticization of Brian–and demonization of Landy (who really did help BW initially)–could’ve used a bit more dimension but what are you gonna do.

- To be honest, I was surprised by how top-drawer the whole thing was. Every time someone has tried to dramatize this material in the past, the powers-that-be torpedo it, the Beach Boys world being what it is. Can’t wait to see the deleted scenes.

- The studio sessions really are sublime. It’d be impossible to walk away from this film with a dismissive attitude toward the music itself.

- I’ll never listen to “Let’s Go to Heaven in My Car” again.

Anyway, here’s the Pet Sounds portion of the Mess of Help essay, which spells out some of the theological implications of the film:

“The advantage of Brian’s willingness to be seen as weak (or his glaring inability to ‘front’ with any conviction) is that he could express gratitude and joy to a similar extent as pain. Some would claim that he penned the greatest song about gratitude that’s ever been written in the American pop idiom, “God Only Knows”—which also happened to be the first time that the word “God” was used in the title of a song that charted on top 40 radio. And Brian & co. were very nervous about that.

In 2012, Brian elaborated on what was going on when he was writing and recording the song:

“Carl and I kept praying for the highest love to bring to people. We all in the band believe in Jesus and we believe in God and we believe that we were his messengers. So we followed through with our career as his messengers in the world. And that’s how we did it. Spirituality is love, right? Love and spirituality are kind of like the same. But spirituality is like ever-lasting love.”

The truism that vulnerability is the birthplace of connection echoes the theology of the cross. It contradicts the human intuition that our most impressive accomplishments and proudest attributes are what will win us the admiration of others (and of God). It affirms the reality that to love someone truly is to love them at their worst, not merely at their best. As columnist Tim Kreider once memorably observed in The New York Times, “if we want the rewards of being loved we have to submit to the mortifying ordeal of being known”. Meaning, we can know someone and not love them, but we cannot love someone if we do not know them: to know someone fully is to know them in their weakness and shame.

The truism that vulnerability is the birthplace of connection echoes the theology of the cross. It contradicts the human intuition that our most impressive accomplishments and proudest attributes are what will win us the admiration of others (and of God). It affirms the reality that to love someone truly is to love them at their worst, not merely at their best. As columnist Tim Kreider once memorably observed in The New York Times, “if we want the rewards of being loved we have to submit to the mortifying ordeal of being known”. Meaning, we can know someone and not love them, but we cannot love someone if we do not know them: to know someone fully is to know them in their weakness and shame.

Perhaps it was Brian’s preternatural vulnerability that situated him, then, to appreciate the experience of grace in such transcendent and enduring terms, as songs like “She Knows Me Too Well” and, much later, “Love and Mercy” attest. Or take Pet Sounds’s stunning hymn to ‘love to the loveless shown’, “You Still Believe in Me”. The grace of Asher’s lyric is underlined by the abundant giftedness of its damaged producer: “I know perfectly well I’m not where I should be… And after all I’ve done to you, how can it be, You still believe in me”. The lover meeting the beloved at his point of (persistent) failure and weakness—his lack of deserving—is enough to remind the listener of another supremely cracked vessel named Peter, talking to his risen lord over breakfast on, you guessed it, the beach.”

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply