Originally posted on Tides of God.

PART I: FALL

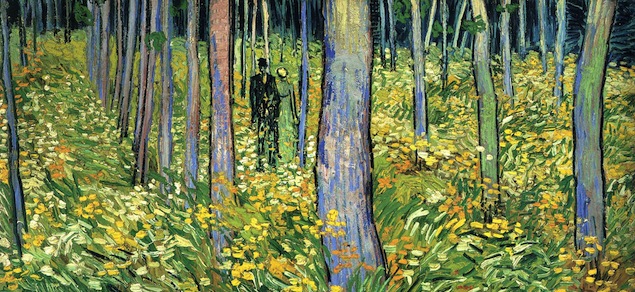

Undergrowth with Two Figures is the only Van Gogh painting I have seen in real life. Several times my wife and I have sought it out on visits to the Cincinnati Art Museum. It is not one of Van Gogh’s well-known paintings. The work was completed during his almost manic period of productivity from May to July 1890 when Vincent turned out nearly one hundred paintings and drawings in the last seventy days of his life. Undergrowth with Two Figures is an island of peace in sea of turmoil. Van Gogh biographer Philip Callow describes the painting:

. . . a woodland scene of absolute serenity . . . Nothing is rushed anywhere, the pressure of time has been abolished, and we float down before the peaceful upright lines of young trees. . . . Colors are quiet soft harmonies of white, yellow, speckled green, and lilac. Among these tree and sapling figures move a man and a woman, perhaps lovers walking close together over the soft ground of yellow and white flowers into dense undergrowth. A succession of downward stroked verticals, falling simply like strokes of filtered rain, has brought this magical rendering of a lost domain to pass. Adam and Eve walk again in the cool of the evening.

It was almost as though Vincent was trying to paint a life he knew he could never have.

Van Gogh’s life was a complete failure, by any worldly measure of success. His father was a small town pastor in the Dutch Reformed Church. At age sixteen Vincent began an apprenticeship with an art dealership that an uncle established in Paris. After seven difficult years he resigned in frustration (he expected to be fired anyway) at what he considered the commercialized betrayal of art. He worked as an assistant teacher for awhile near London, but shortly returned to Holland.

Always devoted to the Church, the Bible, and the example of Jesus Christ, Vincent next turned to the ministry. He began theological training, but found it both difficult and irrelevant, so he quit after a few months. He attended a three-month course for lay preachers, but after his final examination the examiners found him unsuitable for the ministry. On his own, he moved to a poor coal-mining region of Belgium to serve the miners and their families. He eventually obtained an official commission from his mission school, but lost this after three months due to his supposedly poor preaching skills, despite his undeniable and even extreme devotion and service to the coal-miners.

Vincent lost in love as he lost in vocation. At age twenty, he fell in love with Eugenia Loyer, the daughter of his landlord in London. She rejected him as passionately as he declared his love for her. Eight years later, he proposed to his widowed cousin—a young mother—and again was firmly rejected. The following winter, while studying art in The Hague, he met and moved in with an alcoholic prostitute, Sien Hoornik, who already had one child and was pregnant with her second. Vincent’s attachment to her was probably born of equal parts Christ-like devotion to save her from her plight, and his deep-seated longing for a happy domestic life—an ideal that was deeply rooted in Van Gogh’s psyche. Callow writes, “He saw her as a person injured by life, as he was injured.” Vincent wrote, “Nobody cared for her or wanted her, she was alone and forsaken like a worthless rag.” He was speaking as much about himself as he was about her. Only with difficulty did his family dissuade him from marrying Sien. Not surprisingly, this relationship ended badly also.

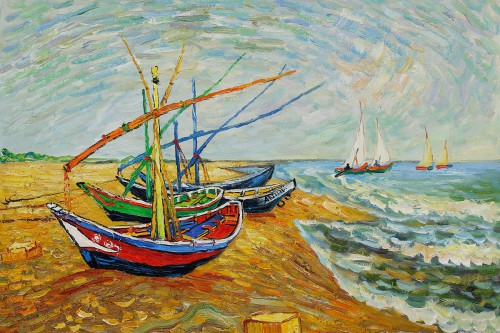

As a working artist, Vincent was an utter financial failure. He was always dependent on the allowances regularly sent to him by his brother, Theo, who was an art dealer with the same firm Vincent had left. During Vincent’s lifetime he sold a few drawings and exactly one painting. In 1890 he sold The Red Vineyard, for 400 francs. The Red Vineyard had been painted during Vincent’s sojourn in Arles, France from 1888 to 1889. It was here that he painted some of his best-loved paintings, including Cafe Terrace on the Place Du Forum, The Night Cafe, Starry Night Over the Rhone, and Fishing Boats on the Beach of Saintes-Maries.

But Arles would also be where Vincent would begin to finally lose his life-long struggle with mental and emotional stability. It was here where he cut off a piece of his ear- lobe and immortalized his own self-mutilation in Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear and Pipe. In the hospital at Arles, he recovered from his wound, and regained some of his mental stability. But it would not last. Not long after, he admitted himself to the mental hospital at St. Remy, about twenty miles from Arles. He was not restricted to the hospital, and at St. Remy he continued to work prodigiously, producing dozens of paintings, including his most famous, Starry Night. After several weeks and two relapses, Vincent left the hospital in May 1890 to live in Auvers-sur-Oise, near Paris, where his brother Theo lived with his wife Johanna. He continued to pour himself into his painting, producing new works almost daily. In June, he completed Portrait of Doctor Gachet, which will sell exactly one century later for 82 million dollars, the most expensive Van Gogh painting ever sold. That same month he painted Undergrowth with Two Figures. In July he painted over two dozen works, including what is often thought to be his last painting, Wheatfield with Crows. Of this work, Vincent wrote, “I did not need to go out of my way to express cheerlessness and extreme loneliness in it”, but also that the painting expressed, “the health and forces of renewal that I see in the countryside.” His words as well as his painting convey the troubled melancholy he could never shake and his unquenchable passion to know and express joy. On July 27th, Vincent went for a walk in the fields outside Auvers and shot himself in the chest with a revolver. He died two days later.

PART II: REDEMPTION

“The world breaks everyone and afterward many are strong at the broken places,” Ernest Hemingway famously wrote in A Farewell to Arms. Van Gogh was not to be one of the many who were strong at the broken places (nor, for that matter, would Hemingway). Vincent never adjusted to the world, and when the world, in its intractability, would not adjust to him, Vincent resolved, in his own fitful way, to end the relationship.

While Vincent lived with the world—it is hard to describe him as living in the world—he dealt not only with the typical developmental issues of moving from adolescence to adulthood, but also he likely suffered from what would now be called bipolar disorder. However, even his periods of elation and creativity were tempered by the genuinely dismal existential circumstances that were often the backdrop of his life.

He was sustained in his struggle with the disjuncture between a world he envisioned and the one he experienced by an intuitive faith in God. Vincent looked to Christ not solely as a religious figure, but, as Rainer Metzger put it, “Jesus Christ was the personification par excellence of his own view of the world.” This view was life as the way of suffering, while ever seeking consolation and joy. In his first sermon in Isleworth, England, Vincent’s conclusion expresses this life motif in a verbal painting:

I once saw a beautiful picture: it was a landscape, in the evening. Far in the distance, on the right, hills, blue in the evening mist. Above the hills, a glorious sunset, with the grey clouds edged with silver and gold and purple. The landscape is flatland or heath, covered with grass; the grass-stalks are yellow because it was autumn. A road crosses the landscape, leading to a high mountain far, far away; on the summit of the mountain, a city, lit by the glow of the setting sun. Along the road goes a pilgrim, his staff in his hand. He has been on his way for a very long time and is very tired. And then he encounters a woman, or a figure in black, reminiscent of St. Paul’s phrase: ‘in sorrow, yet ever joyful’. This angel of God has been stationed there to keep up the spirits of the pilgrims and answer their questions. And the pilgrim asks: ‘Does the road wind uphill all the way?’ To which comes the reply: ‘Yes, to the very end.’ And he asks another question: ‘Will the day’s journey take the whole long day?’ And the reply is: ’From morn to night, my friend.’ And the pilgrim goes on, in sorrow, yet ever joyful.

“In sorrow, yet ever joyful,” the apostle Paul’s description of his own pilgrim journey (2 Corinthians 6:10), would be the continual refrain of Van Gogh’s. He once decorated his rented room with prints of biblical scenes, and beneath each picture of Christ he inscribed those words, “In sorrow, yet ever joyful.” Vincent himself painted very few religious subjects. He did not so much want to depict Christ as emulate him; first in his failed attempt at being a minister, and then through his art. Vincent eventually gave up on the Church that had so disappointed his aspirations and his art took the place of religious observance. But he never gave up Jesus Christ. As Philip Callow put it, “Christ, however, remained exempt. As the greatest of all artists, one who worked ‘in living flesh,’ he still reigned supreme.”

Given his sensibilities and his circumstances, we would expect Van Gogh’s art to reflect more and more his ongoing depression and troubled emotions. Yet somewhat the opposite is true. Vincent’s earlier paintings, such as The Potato Eaters (1885), have a limited color range of dark earth tones. The scene itself is somber, reflecting the hard life of Dutch peasants that he wanted to faithfully represent. From 1886 Vincent’s palette became lighter and more vibrant. Many paintings still clearly reflect the agitation of his soul, but we also see the longing to know and express joy. In sorrow, but ever joyful.

If we merely feel pity for Vincent we have missed the point. We are all in the same predicament. Many of us have simply better socialized ourselves with the coping mechanisms, entertainments, and venues for escapism of contemporary life. I have wondered what would have become of Van Gogh if he had had available to him the benefits of our modern culture. Perhaps he could have been a successful businessman and family man. Would that really have satisfied his unrequited longing, or just dulled his senses?

We also need to be wary of seeing Vincent as the Romantic misunderstood genius whose art was an expression of knowledge that lesser mortals could not share. Art is not a mystic portal to secret knowledge known no other way. But great art does change us. In fact, that is one hallmark of great art, its capacity to make us see and hear and even feel things in different and more expansive ways. My experience is enlarged because of Van Gogh’s art. I see starry nights and night cafes, seacoasts and sunflowers, and expansive fields of wheat, and chairs and shoes, and my own life, differently.

“Hope for consolation was in fact the true mainspring of his art,” Metzger said of Vincent’s work. Van Gogh expressed in his art joy and light which he himself rarely, if ever, experienced. What, indeed, could be more beautiful—and redemptive—than such an accomplishment? Because I am pretty sure Hemingway was not quite right. The world does indeed break us all, but I don’t think many of us are made strong. We mend as best we can and move on. We may learn, but eventually the accumulation of breaks always takes its toll. There is no final strength—not in this life anyway. Perhaps the best we can do is leave fragments that lend meaning to our brokenness and offer others hope for consolation. This is what Vincent did, and I am grateful that he did.

COMMENTS

3 responses to “A Life of Aching Beauty: Vincent van Gogh as Preacher, Failure, and Painter”

Leave a Reply

Loved this piece, Mike. Nice to hear from a fellow Louisvillian! I live in the Highlands, attend Highland Baptist… Anyway, I find it curious that most of the richest beauty we experience in life is indeed an “aching” beauty, perhaps even tragic. Why is Van Gogh as a man, or Christ for that matter, so supremely beautiful to us after all these years? I don’t exactly know. Anyway, if you ever happen to make it to Holland, the Kroller Muller and Van Gogh museums alone make it worth the trip.

Thank you, Benjamin! I think real beauty always beckons us to a transcendent reality which we can never quite grasp in this world–hence the aching, and longing for a certain “we-know-not-what” just beyond our experience. I hope I can make it to Holland some time!