(Spoilers for George Eliot’s Middlemarch ahead.) Dorothea was a devout and idealistic girl whose greatest desires were to help other people and to serve some high purpose for God. When she met Mr. Casaubon, a scholarly middle-aged man in the midst of writing his opus, a “Key to All Mythologies”, she saw a chance to serve him dutifully as a wife (it was 1830 or so) and was thrilled to be a part of this higher purpose. Yet Casaubon is vain, self-important, and deeply insecure. Dorothea has overestimated both her capacity to sacrifice all for him and has overestimated Casaubon’s value as a scholar: they went to the Vatican for their honeymoon for Casaubon to do research, leaving Dorothea alone where, melancholy, she learned that Casaubon’s inability to read German might hamper his research into mythology. When they return to their house in the English countryside, she re-enters her boudoir (a woman’s private room in the home), which she had seen little fault in before, reading in a tapestry the stories of great adventures and in the bookshelves a lifetime of erudition. No longer:

The very furniture in the room seemed to have shrunk since she saw it before: the stag in the tapestry looked more like a ghost in his ghostly blue-green world; the volumes of polite literature in the bookcase seemed more like immovable imitations of books. The bright fire of dry oak-boughs burning on the dogs seemed an incongruous renewal of life and glow – like the figure of Dorothea herself as she entered, carrying the red-leather cases containing the cameos for Celia [her sister]…

The duties of her married life, contemplated as so great beforehand, seemed to be shrinking with the furniture and the white vapor-walled landscape. The clear heights where she expected to walk in full communion had become difficult to see even in her imagination; the delicious repose of soul on a complete superior intellect [Casaubon’s] had been shaken into uneasy effort and alarmed with dim presentiment. When would the days begin of that active wifely devotion which was to strengthen her husband’s life and exalt her own? Never perhaps, as she had preconceived them; but somehow – still somehow. In this solemnly-pledged union of life, duty would present itself in some new form of inspiration and give a new meaning to wifely love… Her blooming full-pulsed youth stood there in a moral imprisonment which made itself one with the chill, colorless, narrowed landscape, the shrunken furniture, the never-read books, and the ghostly stag in the pale fantastic world that seemed to be vanishing from the daylight.

It’s almost impossible, outside of poetry, to find language so saturated with emotion and meaning, and so precise at the same time. It’s tragic to watch Dorothea’s high hopes for her life, bound up in intense Christian devotion, start to run aground on the hidden reefs of her husband’s coldness, the likely futility of his life’s work, and the emerging reality that she simply cannot handle her marriage and be happy – in short, of human nature.

One of Eliot’s strengths is the use of well-developed symbols to describe the mundane, and here is no exception; it’s model writing. Symbols tend to work when their literal sense is closely united to their figurative sense: when they work both as concrete, plausible elements of a story and as devices to convey further meaning. These senses are so joined in the passage above that only a shade separates them:

1. “Immovable imitations of books”: Given the action’s happening in a manor, this is very plausible; that is, it doesn’t feel like something just inserted to suit the author’s purposes, but it feels like a detail natural to include in this description shaded by Dorothea’s mood. She’s not gloomy, but only the cheerfulness and liveliness she once projected onto the room is fading, as with her husband, who seems like more and more of the ‘dried-up pedant’ the rest of the town thinks he is. The books are no longer there to be read or handled or moved, but seem only like adornments, lifeless objects from some distant past to which she has little relation. Her husband’s once-exciting vistas of knowledge seem false, dead, calcified, and impersonal.

2. “White vapor-walled landscape”: Just a foggy day in the country, but the rest of the world feels impenetrable to her; her aspirations and life have shrunk to the confines of this manor with a lifeless husband. It leads beautifully into the next sentence, about the circumscription of even her imagination: Eliot moves from the physical to the spiritual with almost the same felicity as John’s Book of Signs, and it doesn’t feel a bit artificial or forced.

3. The tapestry and the stag: Stags have long been a symbol for Christ, and tapestries family heirlooms which connect the confines of the home to the greater story of the world beyond. So the tapestry of the stag is a sort of great mythology wherein someone may see Christ, and it graces the Casaubon home, opening Dorothea’s small world onto spiritual vistas and uniting the story of Providence with that of her new life. But now the stag looks like “a ghost in his ghostly blue-green world”: through a new, slightly less enchanted emotional lens, Dorothea feels the spiritual world, or any world beyond, is something remote and ghostly. As the daylight comes – and again, nothing is forced here, as glare always makes pictures seem to fade – the stag seems to be vanishing. In the metaphorical night of courtship Dorothea had mentally made up for Casaubon’s defects, had “filled up all blanks with unmanifested perfections, interpreting them as she interpreted the works of Providence, and accounting for seeming discords by her own deafness to higher harmonies. And there are many blanks left in the weeks of courtship, which a loving faith fills with happy assurance.” But now in the harsh light of day, both her hopes for Casaubon and her intimation of Providence’s “higher harmonies” are fading before the advance of the cold facts of her situation.

As a sidenote, Eliot’s ability to write convincing religious characters is almost unmatched. But going back to the symbols above, what makes them so powerful is that they don’t feel like an author’s craft. Instead, we make symbols out of physical details all the time: in memory, we cannot think of important events or places from our lives without emotional moods or vague portents of personal significance inextricably attached to them. Memory suffuses our present experience, too; if I see a blue Volvo sedan, some vague thought of my first friend to turn 16, with eight or ten of us piling into his blue Volvo, stirs in my mind, along with that entire summer’s general mood and feeling. These associations come constantly and involuntarily: in the most famous modern lit example, Marcel Proust’s narrator tastes a madeleine in Swann’s Way, triggering an entire book’s worth of reminiscence. Perceptions, too, layer in our minds: on top of my normal associations with bread and wine at church, comes the slightest triggering of a lifetime’s stacked associations and emotions from church. Good writing, like Eliot’s above, often does not co-opt a mundane object to bear significance arbitrarily, but instead taps into the character’s process, and ours, of an endlessly semiotic subjective life.

Speaking of memory, how many of us can remember a time when, like Dorothea in courtship, we had lives which seemed saturated in every detail by Providence? These moments are often embarrassing: the whole world seems to coalesce in a newfound faith, or friend group, or professional venture, or first infatuation or relationship. In these moments, which seem to occur most frequently in middle school through college, the whole world seems graced by a singular higher purpose, around which everything else seems to dance (perichoresis) or toward which everything seems to move. For me, it was my personal increase as a servant of God: I recently found, in a notebook from freshman year of college, “Every trial is a tool for my sanctification.” Even suffering becomes caught up in this: the redemptive suffering of the saint; the falterings of a business through which every great entrepreneur persevered; the romantic’s unrequited love, which serves to prove love’s purity; all of the many blanks ‘filled with happy assurance.’ The only purposes which can bear to have the whole world drawn up into them, to have one’s mind make of all else in life symbols which point to this one good; these purposes tend to be tangible, promising, and self-elevating ones. Dorothea’s religion was naive, and she held that happy assurance in mutual dependence with her purposeful ignorance of much of human sin and limitation and suffering.

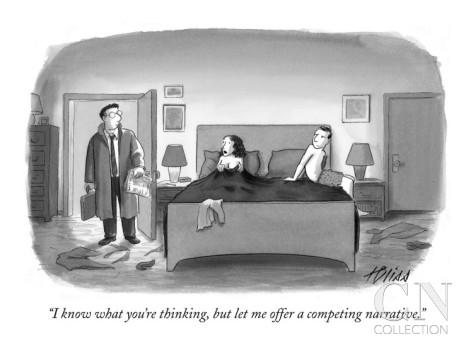

Certain types of suffering could be called de-narration or de-signification. I once had a crush on a girl, about ten years ago, which was going nowhere, almost entirely in my head. I had somehow determined, despite a decent grasp of Christian theology, that God had promised me this particular thing would work out – all temporary setbacks were a test. It turned out, of course, that the setbacks signified something quite different: they signified both a general paralysis on my part from overthinking, and a total lack of interest on her end. The everyday interpretations of the “signs of the times” turned out to be the correct ones. And the narrative I’d imposed on the situation, of setbacks followed by eventual fulfillment, was wrong. My own symbol-making turned out to be informed perhaps more by typical adolescence than by an accurate reading of Providence’s design. And this deconstruction of our narratives and naive significances happens all the time, even when experience and age have tempered have our naivete.

The world at large has undergone the same shift in its aging process: the arrival of God’s kingdom in Constantine’s conversion of Rome to Christ was shattered by Rome’s fall, a disillusionment so great that even Augustine’s enduring work could barely soften the blow. The Eastern and Western Churches split, then the West itself fragmented; all of history was no longer quite so clearly permeated by Providential design. Copernicus found that the entire universe does not, as was supposed, move about the world of Man; and Kant made it very difficult to continue speaking about the higher world. History moved on after Hegel had found its completion in high purpose, and Marx’s perfection of world economy ended in corruption, violence, and impoverishment. The world no longer seems to work toward some higher purpose, Providential or philosophical or economic, and all we know of faith is the sound of its “long, melancholy, withdrawing roar”, leaving behind the “naked shingles” of a de-signified, de-narrated world. (Matthew Arnold).

Yet we spin these stories in memory and experience still because we need to, sensing (whether right or wrong, but sensing still) that there must be some purpose to things beyond what we can see, that Arnold’s naked shingles must be graced in some way. I have followed this process religiously, realizing that world does not exist for my sanctification, that God promises me many things, but not necessarily happiness. And though things are good, the passage from the naive, anthropomorphic, and purpose-filled world of a Christianity of youth can leave, if a more responsible faith, that sound of withdrawing, the sense that things are de-signified naked shingles, that sound is not necessarily word and breath, but may be mere fury.

As the world dies to the old, naive superstitions, a task for theologians will be to re-enchant history somehow without falling into the same triumphalism which tempted people like Hegel or Marx to use much of their gifts for, at some level, arbitrary narratives. And a task for pastors will be to mediate between the folding of Providence into human goals and the sense of Providence’s total absence in day-to-day affairs, searching for third way.

As the world dies to the old, naive superstitions, a task for theologians will be to re-enchant history somehow without falling into the same triumphalism which tempted people like Hegel or Marx to use much of their gifts for, at some level, arbitrary narratives. And a task for pastors will be to mediate between the folding of Providence into human goals and the sense of Providence’s total absence in day-to-day affairs, searching for third way.

Mr. Casaubon’s “Key to All Mythologies”, by which he apparently meant to recast all human mythologies through one lens which would point them to Christ, failed. The book was itself a sign of Casaubon’s pompous grandiosity; things are not as intellectually unifiable as he supposed, and his search for Providence’s Key blinded him to the enjoyment of smaller things: for instance, he failed as a husband because he tried to draw Dorothea into his great work, viewing her as an instrument of his idea of Providence and, in the process, shattering hers. Eliot’s narrator makes fun of Casaubon, though not unsympathetically, because his narrative is so blatantly overblown and overambitious. And one way to describe much of modern literature would be the parodying of old narratives and the exposure of their failure; postmodern literature, of course, has undertaken the project of (literal) de-narration with aplomb.

Grace pushes against many of these naive significations by changing the subjectivity out of which they grow. Casaubon’s own insecurities, mingled with self-importance, made marriage seem like merely a support for his work from the outset. And other naive significations derive from our motives as fallen creatures, the needs to be important, to be loved, to push away guilt. Good theology or healthy doses of reality – ‘trials aren’t necessarily a tool for your sanctification, they’re just bad things that happen’ – must lead either to new forms of narcissistic narration or a complete disenchantment, leaving only the naked shingles of the world. And this is, indeed, all that’s left on Good Friday – a point which every believer must pass through, in such a way that it always remains with them – and beyond that the wait for new meanings, new stories, and new beginnings as God continues to be the God of promise and resurrection, and the Spirit blows where it will.

COMMENTS

One response to “On Symbols, Dutiful Wives, and Religious Recessions”

Leave a Reply

What a fantastic concluding paragraph! Love it. Thanks, Will.