There’s one particularly ‘seasonal’ portion of A Mess of Help, and here it is (minus the copious footnotes). Longtime readers may recognize portions, but this is the published and much-expanded version, which comes in the book’s final chapter, track nine of “Sing Mockingbird Sing: The Alpha and Omega of Annotated Playlists”. Enjoy:

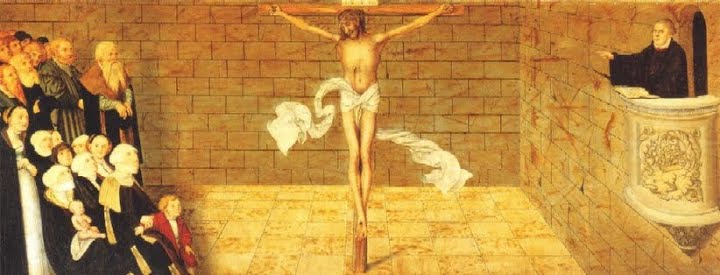

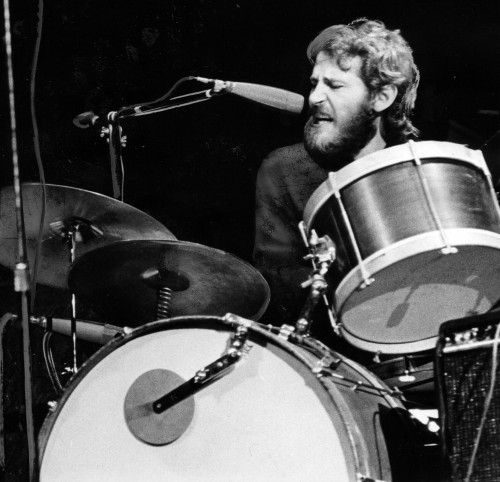

I am quite proud of my office. It has taken a decade or two, but I finally feel like I’ve collected a suitable constellation of mementos to display. There’s the foldout from the ET: Picture Book record, which has Michael Jackson posing for what appears to be a school photo with the Extra-Terrestrial himself. There’s the 7-inch Slash figurine, with adjoining Marshall stack, situated to the right of a framed reprint of Lucas Cranach’s Marienkirche altarpiece, which depicts Martin Luther preaching the crucified God. Across the room sits the picture sleeve of Brian Wilson’s “Love and Mercy” single, which faces the NY Times obituary for Robert Capon and a print of one of Kathe Kollwitz’s Lord’s Prayer woodcuts. Am I justified yet?! If not, amidst the clutter of one of the bookshelves hides a drum tom signed by one Levon Helm.

I am quite proud of my office. It has taken a decade or two, but I finally feel like I’ve collected a suitable constellation of mementos to display. There’s the foldout from the ET: Picture Book record, which has Michael Jackson posing for what appears to be a school photo with the Extra-Terrestrial himself. There’s the 7-inch Slash figurine, with adjoining Marshall stack, situated to the right of a framed reprint of Lucas Cranach’s Marienkirche altarpiece, which depicts Martin Luther preaching the crucified God. Across the room sits the picture sleeve of Brian Wilson’s “Love and Mercy” single, which faces the NY Times obituary for Robert Capon and a print of one of Kathe Kollwitz’s Lord’s Prayer woodcuts. Am I justified yet?! If not, amidst the clutter of one of the bookshelves hides a drum tom signed by one Levon Helm.

I fell under the spell of The Band the moment the needle hit my father’s copy of the brown album when I was ten years old. That record still conjures up its own peculiar universe— “the old, strange America” found in its sepia-toned Civil War imagery, ragged singing, and instrumental backing that sounds more like the work of a single, ten-handed organism than five individuals. It was music made by men, not boys.

Like many before me, I sought out everything of theirs I could find: the haunting Music from Big Pink; the strung-out Stage Fright; the labored, if still criminally underrated, Cahoots; the rather academic, but no less enthralling, Northern Lights-Southern Cross; the charming afterthought of Islands. And then there are the live albums, particularly Rock of Ages, which somehow lives up to its ultra-sympathetic title. If they don’t have you completely hooked by the second “my biggest mistake was lovin’ you too much” of “Don’t Do It”, it might be time to check your pulse.

One of the wonderful things about The Band is that there never was a star or a frontman. Everyone carried the, er, weight in that regard. As their ungoogleable name suggests, The Band was anti-celebrity, anti-solos, a group in the purest sense, much more than the sum of its parts. Perhaps the democratic spirit is part of why their music has come to define the term ‘Americana’. Ironically, Levon was the sole American in the group—all the other guys were from Canada. But his Southernness rooted the group, with his adopted brothers appropriating, via osmosis, the old-as-the-hills pathos that seemed to flow through the Arkansas native’s veins.

Jon Carroll famously described Levon as “the only drummer who could make you cry”, and I always assumed he was referring to Levon’s inimitable thud on the snare, which does indeed have a sadness to it. But there was something else that you can hear in his playing, especially his voice, that Carroll may have been alluding to, something tragic. In her essay, “The Regional Writer”, Flannery O’Connor described it this way:

“When Walker Percy won the National Book Award, newsmen asked him why there were so many good Southern writers and he said, ‘Because we lost the War.’ He didn’t mean by that simply that a lost war makes good subject matter. What he was saying was that we have had our Fall. We have gone into the modern world with an inburnt knowledge of human limitations and with a sense of mystery which could not have developed in our first state of innocence—as it has not sufficiently developed in the rest of our country.”

Flannery’s diagnosis would certainly account for the opening line of Bernie Taupin and Elton John’s remarkable tribute to Helm, “Levon wears his war wound like a crown”. And is there a better song about defeat than “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down”?

Flannery’s diagnosis would certainly account for the opening line of Bernie Taupin and Elton John’s remarkable tribute to Helm, “Levon wears his war wound like a crown”. And is there a better song about defeat than “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down”?

Then again, if Flannery’s right, one would surmise that The Band’s music would have touched on themes eternal more often.

The main exception to their ostensible secularism would have to be their left-field seasonal classic, “Christmas Must Be Tonight”, which lifts much of its lyrics directly from the King James. “Come down to the manger / see the little stranger”, it begins, placing the listener squarely in the middle of the action, before unfolding the events from a shepherd’s point of view.

But the song captures more than the facts; it captures the feeling of that fateful day as well, even some of the meaning. “How a little baby boy / bring the people so much joy”, sing Rick and Levon in unison, and you can’t help but reflect on the counter-intuitive beauty of a God who would reveal himself in such weakness and vulnerability, such seeming insignificance. When Rick asks, “Why a simple herdsman such as I?”, the sense of awe at the undeserved-ness runs deep.

The Band included the song on their final studio record, Islands, and it was the out-and-out highlight of a swansong that was as much a contractual obligation as a cohesive work of art. “Christmas Must Be Tonight” provided both an unexpected shot of religious devotion as well as proof that if substance abuse and ego hadn’t sidelined the group at the end of the 70s, long may they (might) have run. Alas, that wheel was on fire after all.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply