One of my all-time favorite posts from our “early years” is the NY Times Magazine article from 2009 about a man who was horrified to learn that he liked Celine Dion. The realization came during an email exchange with an official at Pandora, the free internet music service that creates custom playlists based on your personal taste. Apparently the man in question was upset by the Canadian diva’s conspicuous appearance on his curated Sarah McLachlan station—there must be some mistake! He was assured by their staff that the algorithm was functioning well. The Pandora official explains: “’I wrote back and said, ‘Was the music just wrong?’ Because we sometimes have data errors,’ he recounts. ‘He said, ‘Well, no, it was the right sort of thing — but it was Celine Dion.’ I said, ‘Well, was it the set, did it not flow in the set?’ He said, ‘No, it kind of worked — but it’s Celine Dion.’ We had a couple more back-and-forths, and finally his last e-mail to me was: ‘Oh, my God, I like Celine Dion.’” It’s not unlike someone who takes pride in their visual sensibility realizing their favorite painting was made by none other than this guy.

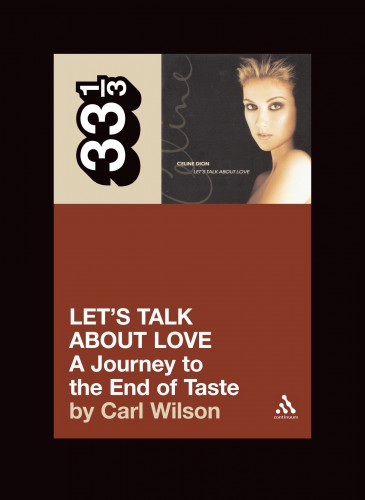

We’ve talked (too) many times before about how potent the area of personal taste is when it comes to identity and self-justification, music being just one particularly blatant area. Décor, food, literature—it’s often difficult to separate what we genuinely like from what we feel we should like, i.e., what such-and-such kind of person who we aspire to be likes. Joey broached the subject beautifully a few weeks ago, discussing the judgment and shame implicit in calling things “guilty pleasures”, and what the discrepancy between the musical preferences we list on our social media and the “most-played” in our iTunes has to say about us. It’s no coincidence that the event that prompted his post was the new edition of Carl Wilson’s Let’s Talk About Love: Why Other People Have Such Bad Taste, a book-length exploration of why people (including the author himself) detest Celine Dion. Maybe you remember that episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer where Buffy discovers that her new college roommate is a demon, her first clue being the Celine Dion poster she hung on the wall? Wilson isn’t making this stuff up; ‘Celine hate’ may have subsided a bit since Titanic days, but the feeling was almost universal among critics at one point. To explore what was going on, he has to explore the very nature of taste itself:

We’ve talked (too) many times before about how potent the area of personal taste is when it comes to identity and self-justification, music being just one particularly blatant area. Décor, food, literature—it’s often difficult to separate what we genuinely like from what we feel we should like, i.e., what such-and-such kind of person who we aspire to be likes. Joey broached the subject beautifully a few weeks ago, discussing the judgment and shame implicit in calling things “guilty pleasures”, and what the discrepancy between the musical preferences we list on our social media and the “most-played” in our iTunes has to say about us. It’s no coincidence that the event that prompted his post was the new edition of Carl Wilson’s Let’s Talk About Love: Why Other People Have Such Bad Taste, a book-length exploration of why people (including the author himself) detest Celine Dion. Maybe you remember that episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer where Buffy discovers that her new college roommate is a demon, her first clue being the Celine Dion poster she hung on the wall? Wilson isn’t making this stuff up; ‘Celine hate’ may have subsided a bit since Titanic days, but the feeling was almost universal among critics at one point. To explore what was going on, he has to explore the very nature of taste itself:

“Everyone has a taste biography, a narrative of shifting preferences: I remember at age twelve telling people I liked ‘all kinds of music, except disco and country,’ two genres I now adore… At twelve, my dislike of disco and country didn’t feel like a social opinion. It felt like a musical reaction. I flinched at the very sound of Dolly Parton or Donna Summer, as unaware that I had any choice about finding them stupid as I was of the frameworks in which they were smart. It seemed natural: I hated disco and country, as cleanly and purely as I now hate Celine Dion…”

Wilson’s book had a big impact on me when it first came out in 2007 as a little 33 1/3 book looking specifically at Dion’s 1997 record Let’s Talk About Love. I had spent a few years after college flirting with the idea of pursuing music journalism full-time, and Wilson’s book put into words much of why I decided not to take the plunge (outside of the fact that there was no money involved). In my admittedly minor forays into the field, I had encountered an orthodoxy of cool that was simply too tempting/overpowering to a young man whose aesthetic convictions (and self-confidence) were less than fully formed. I also couldn’t shake the suspicion that the culture of professional criticism contained an undercurrent of despair. Looking back, I had probably just fallen victim to Camille Paglia’s assessment in Glittering Images of contemporary education, where “students are now taught to look skeptically at art for its flaws, biases, omissions, and covert power plays. To admire and honor art, except when it conveys politically correct messages, is regarded as naïve and reactionary.” As she suggests elsewhere, adopting such an outlook can be inwardly corrosive.

I mean, why was I assigned a lengthy reappraisal of ABBA’s catalog (a worthy endeavor, btw), yet saying anything positive (or anything at all!) about the new Matchbox 20 record was anathema? It seemed so arbitrary and transparently silly. What started out as a lot of fun quickly became an exercise in looking over my shoulder, always wanting to be sure my opinions were the right ones. Live by the sword, die by the sword and all that. Having authoritative taste in cutting edge music is a particularly cruel mistress, especially in an age when technology has put so many extra players on the field. I gave up.

Anyway, since its initial release, Wilson’s book has come to be seen as a manifesto on “poptimism”– essentially a mammoth pushing back against the notion that commercial obscurity equates to artistic quality and vice versa. But I wonder if that’s a superficial reading, since he doesn’t exactly argue the opposite either, i.e. that something is necessarily good because a lot of people like it. Instead, what strikes me is how thoroughly he deconstructs identity-driven (music) criticism, beginning with his own. Wilson has guts. He calls out the hypocrisy of predominantly “leftist” critics who embrace and perpetuate aesthetic elitism in their writing while claiming to detest it if/when it takes on any financial dimension. He even suggests, implicitly, that these are really flip sides of the same self-justifying impulse, a response to some form of law, the outcome of which is the same, namely, exclusion. But I’ll let him speak for himself. Suffice to say, the implications extend far beyond pop music:

Certainly a critical generation determined to swear off elitist bias does seem called to account for the immense international popularity of someone we’ve designated so devoid of appeal. Those who find Dion “naff”– British for tacky, gauche, kitschy or, as they say in Quebec, ketaine–must be overlooking something, maybe beginning with why we have labels like tacky and naff. If guilty pleasures are out of date, perhaps the time has come to conceive of a guilty displeasure. This is not like the nagging regret I have about, say, never learning to like opera. My aversion to Dion more closely resembles how put off I feel when someone says they’re pro-life or a Republican: intellectually I’m aware how personal and complicated such affiliations can be, but my gut reactions are more crudely tribal.

Musical subcultures exist because our guts tell us certain kinds of music are for certain kinds of people. The codes are not always transparent. We are attracted to a song’s beat, its edge, its warmth, its idiosyncrasy, the singer’s je ne sais quoi; we check out the music our friends or cultural guides commend. But it’s hard not to notice how those processes reflect and contribute to self-definition, how often persona and musical taste happen to jibe. It’s most blatant in the identity war that is high school, but music never stops being a badge of recognition. And in the offhand rhetoric of dismissal–“teenybopper pap,” “only hippies like that band,” “sounds like music for date rapists” — we bar the doors of the clubs we don’t want to claim us as members. Psychoanalysis would say our aversions can tell us more than our conscious desires about what we are, unwillingly, drawn to. What unpleasant truths might we learn from looking closer at our musical fears and loathings, at what we consider “bad taste”?

The Celine Dion fan club roster that many non-fans picture was outed with bracingly open elitism by the Independent on Sunday in the UK in 1999, in the paper’s “Why are they famous? series: “Wedged between vomit and indifference, there must be a fan base: some middle-of-the-road Middle England invisible to the rest of us. Grannies, tux-wearers, overweight children, mobile-phone salesmen and shoppingcentre devotees, presumably.”

Reading that, my heart swells for these maligned wearers of inappropriate tuxedos, these poignantly tubby prepubescents pining away to the strains of songs of love sung by a pretty lady with the best voice in the world. And far more than I hate Celine Dion, I hate this anonymous staffer from the Independent on Sunday. But he’s only fleshing our the implication in, for instance, my use of the phrase “Oprah-approved.” If his portrayal of Dion’s audience is accurate, it includes mostly people who, aboard the Titanic, would have perished in steerage. If my disdain for her extends to them, am I trying to deny them a lifeboat?

The Independent’s bile demonstrates why the critical redemption of abject music tends to come years after its heyday: lounge exotica stops sounding like a pathetic seduction soundtrack on the hi-fi of a smarmy insurance salesman and starts to sound charmingly strange, governed by a lost and thus beguiling musical rulebook. In the present tense, submerged social antagonisms and the risk of being taken for one of the “tacky” dullards make it less attractive to be so allembracing–to hear Celine Dion as history might hear her.

Don’t misunderstand: Wilson is not advocating for less discernment when it comes to the things we consume. In fact, some might say he’s arguing for less subjectivity, not more. Because history might not hear Celine in a flattering light after all (even if those rumored Phil Spector productions lurking in her vault do eventually see the light of day!). But these are important questions to be asking, especially by people who look to a Lord who made no bones about bypassing tastemakers in favor of ‘the least of these’. (And what is The Independent’s characterization of the Celine Dion fan club if not a description of modern-day lepers?)

This is where the real thrust of Wilson’s argument becomes clear: identity-related concerns get in the way, not only of how we regard music or art (or worship!), but how we regard other people. We begin to view them not as who they are, but who we aren’t. In other words, an inflated sense of taste prevents us from, well, loving. Which is worse than embarrassing, it’s tragic. One can only hope that while attitudes may shift, fashions may change, and reputations may be rehabilitated, the heart (of God) will… go… on.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z7pojjl1XQ4&w=600

P.S. All that said, there are still lines I dare not cross. Thankfully, Camille Paglia has no such compunction.

COMMENTS

5 responses to “A (Quick) Journey to the End of Taste”

Leave a Reply

We begin to view them not as who they are, but who we aren’t. In other words, an inflated sense of taste prevents us from, well, loving. Which is worse than embarrassing, it’s tragic.

I am SOOO guilty of this, even with my own family (wife and kids). I find myself frustrated at times with the “lack” of filter involved in the music, TV, movies, and books they consume…but I absolutely realize that it is really about my snobbery and not their indiscriminate consumption of entertainment. It is something to repent of.

I still gotta agree though and draw the line with Celine Dion. I was out when she rode an elephant down the isle on her wedding day.

This is something I have thought so much about. It is a crucial freedom to be able to stand alone to like what you like because you like it. However, we like things in community, and this is what is distasteful about Celine Dion. She has the wrong community of likers. It is strange how little any of this has to do with musicianship or compositional depth or lyrical power. You might say that part of the artist’s task is to attract the right community of likers; but in a way this isn’t something the artist necessarily has control over.

But the elephant down the aisle thing – I love it.

Forget the elephants, Celine jumped the shark when she covered AC/DC. Now, if she had turned the selection to the style of her power ballads the way a band like the Gimmie Gimmies turned The Carpenters into punk rock–that would’ve been hysterical. (Google that, by the way.) But Dion straight up mimicking Brian Johnson is just disturbing. https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=ReDEUhRXS3U

And Paglia is totally right about Lucas. One, she’s talking about visual art, not storytelling or writing. And two, her assessment says more about modern visual art than Lucas.