Some people have said that the ‘grace message’ can tend toward Gnosticism. Luther’s exposition of St. Paul’s distrust of the Law can feel like a distrust of the restored, peaceful world to which the Law bears witness. The most extreme interpretations of Luther’s “two kingdoms”, with Christianity’s oft-implied indifference to temporal matters, does nothing to help the problem. And the best modern adaptations of his theology have often been indebted to existentialism, or progenitors of it. The Kierkegaard of the Postscript immediately springs to mind (pseudonymously Johannes Climacus), who argued that world-history is a distraction, and the most important thing to focus on is the inner life of the believer. Since then, existentialists often advocated transcending, abrogating, or dispensing with traditional demands of society or seemingly artificial conventions.

Inherent in some of this thought was perhaps an idolatry of individual consciousness, as it impelled its adherents toward a retreat from the world, since so much of the world seems indifferent to the individual. It doesn’t seem like a coincidence that ‘existential’ theologians, such as Tillich and Bultmann, who powerfully on grace, also ended up abandoning concrete forms of the world to focus on the symbols of doctrine – reducing them to a sometimes-abstract New Being (Tillich) or some remainder of abstract truth once the inadequate concrete forms of biblical expression were demythologized (Bultmann). If a believer’s task were to live without reference to the Law, it would present a serious difficulty, since ethics does so much to delineate the forms of real life. The Law does give us a sense of purpose, it gives concrete action in the world deep meaning, and it teaches us that what happens outside the individual does indeed matter. Grace can never be merely about transcending the Law, because that would reduce life to individual consciousness and freedom which, in addition to increasing anxiety, promotes self-absorption.

Christ on the cross deconstructs all our theologies of glory, and it’s precisely an ethically-grounded, world-historical meaning for which Peter expresses attachment when he tells Christ that “this [suffering, death] shall never happen to you!” And Christ critiques his theology of glory – “get thee behind me, Satan” – before going on to “fulfill the law” and release us from it. So Good Friday frees us from the destructive forms of the world, the powers and principalities, the old spiritual idols which gave us purpose and meaning. And yet, Good Friday empties the world in the very act of abrogating the Law. What matters now besides Christian freedom, which, if made primary, tends toward individualism?

Wallace Stevens noted how bleak this deconstruction is, asking why someone should “give her bounty to the dead? / What is divinity if it can come / only in silent shadows and in dreams?” Shadows and dreams are a retreat from the world, and Stevens advocated reengaging this world by finding joy in his famous “complacencies of the peignoir and late / coffee and oranges in a sunny chair.” His critique of Christianity in that poem, “Sunday Morning”, focuses somewhat on its Gnostic elements, finding heaven boring, a projection of earth in which beauty can no longer be seen since its backdrop – change – does not exist.

If Holy Saturday were perpetual, atonement would risk being a destruction of the Old Adam which left us only by ourselves, without the anxiety of the Law, but also without the purpose it provided. It is only the Resurrection which gives us new life, new purpose, which manifests the New Being apart from the Law, as Tillich implies (ST vol II), but which also effects real change. Christianity as a whole has often risked focusing too much on Good Friday, which leaves either moral self-improvement as the believer’s purpose or amorphous Christian freedom.

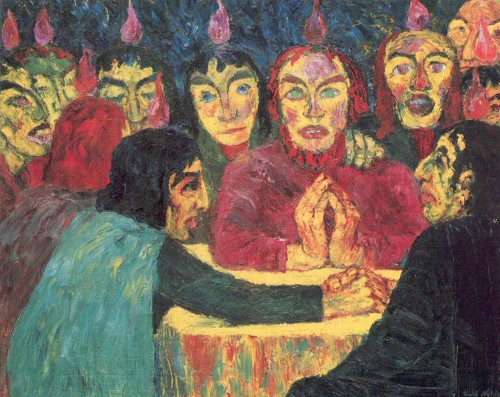

(Smithsonian American Art Museum)

Christian freedom – living without reference to the Law – seems a worthy purpose, but the Resurrection is needed to give such life a form beyond an all-absorbing individual consciousness which falls prey to an existentialist neglect of external forms or a modern obsession with self-actualization, now freed from the Law. What this form looks like is difficult to see, and it may require a turning-back to the original event. Among a good deal of contemporary thought on the issue, Anthony Kelly seems to land in a good place between moralistic “vision of the good” and existentialist indifference to it:

[The Resurrection] provokes humility, wonder, and self-surrender – features of a fresh and more genuine sense of mystery, not as something to be analysed, solved, reduced to a system, but as a gift to be lived.

The concept of “living a gift” seems an appropriate place to land. However much “new life” may be articulated by way of the sacraments, intellectual understanding, mystical experience, or increase in virtue, nonetheless it is always as gift – that primal, category-defying experience of God-given life, life from utter death. The Resurrection strikes us as something incongruous with the old law, which was the power of sin, but also as something which defeats human comprehension and cannot ever be circumscribed by individual understanding.

It’s difficult here to go beyond the place of the Resurrection in theology and into the content of the risen Christ; for that second, more difficult problem, von Balthasar and David Bentley Hart are good places to go. But in terms of what “living a gift” looks like, there are several features of the risen Christ of the Gospels, but in this context, a couple of salient ones are the wounds and the Spirit.

The risen Christ still has wounds, and these wounds work as physical proof for Thomas, who must touch them. The Resurrection does not nullify the Cross, but rather surges forth from it. In Revelation 5, even the glorified Christ, the object of worship, maintains the name “Lamb”, denoting meekness and paschal sacrifice. Christ does not transition from pure victim to pure conqueror, but the sacrifice itself is the sign of his glory. And yet the wounds, while continuing to mark Christ as victim, lose their melancholy; the disciples still have the sacrifice, but no longer the sorrowful expression on the man they knew. This close unity between suffering and gory does not go away; martyrdom, in the early church, would be understood as an archetypal mode of being unified with Christ.

Second, in the Fourth Gospel, the Risen Christ gives the Holy Spirit, the Spirit who works through consolation (glory) and desolation (the cross), both of which draw the believer out of herself. Though its presence is not available on command, and even a little arbitrary (“the spirit blows where it will”), it is also omnipresent, continuing Christ’s identity as Immanuel, “God with us” – “wherever two or three are gathered…”.

The Spirit’s presence, like the Resurrection itself, has sometimes been difficult to pin down, between the extremes of Lutheran suspicion and Pentecostal over-enthusiasm. And like the Resurrection, it escapes our understanding, forcing us to remain open to new possibilities, since we never entirely appropriate God’s action intellectually or experientially. Within this darkness of understanding, we only have promise and story to fall back upon: the promise that the Christ enthroned in heaven is the same one who died for our sins, and the story of someone who defeated death, whose wounds were tangible and who gave us a Holy Spirit to be present with us.

Against the extremes of decisions based on personal, existential self-actualization and an individuality-destroying conformance to an impersonal code of ethics, we have a new life which, though we cannot understand or recognize it, is promised as something which is there with us. As the old calculus of cause-and-effect, righteousness-and-judgment was broken apart by the Resurrection, the “Lamb who was slain” (Rev 5:12) and the Spirit he breathed forth present the possibility of new understanding, new experience, and new life at every turn. Fortunately, we were not given merely a story to be acted upon, but a Person from the story who continues to act upon us, beyond our recognition and always for our good.

COMMENTS

3 responses to “Legalism, Gnosticism, and Resurrection: An Easter Reflection”

Leave a Reply

Fantastic post Will! Thanks for this.

In many ways, it seems to me that the position of Christian theologians from the late 19th century forward is very similar to the situation from 5th century b.c. Athens really to the end of classical paganism, as the concrete reality of the pagan gods came to be seen as intellectually unsustainable. Although these personal gods, among the educated, were not viewed as concretely “real”, there was a strong cultural urge to rescue them, or the profound abstract truths they embodied, through their reinterpretation as illustrations of psychological and existential realities. This impulse seems to be powerfully at work in many modern theologians, who seem to want to rescue the insights of classical Lutheranism or Calvinism, but with the concrete claims of an actual physical resurrection seen as no longer intellectually sustainable, the “rescue” must be toward a highly abstracted version of the original Christian claims. That’s just a layman’s impression, very generally stated. I think this post speaks to this situation very powerfully and shows why it is so important to hang on to the concrete claims made in the NT. In the end, I just don’t think it is possible to separate the abstract truth of the Christian message from its concrete and personal presentation in a personal God with scars who either is or is not.

Great thoughts Will. I love your summary – being stirred by the mystery, despite a darkened understanding, doesn’t diminish our hope – it ignites it. Good stuff man.