1. What happens when you combine an unshakeable superiority complex with deep insecurity? Probably a nervous breakdown in mid-life, or Whit Stillman’s Metropolitan. But Amy Chua (of “Tiger Mother” fame) asks us to guess again. The real answer is… success.

1. What happens when you combine an unshakeable superiority complex with deep insecurity? Probably a nervous breakdown in mid-life, or Whit Stillman’s Metropolitan. But Amy Chua (of “Tiger Mother” fame) asks us to guess again. The real answer is… success.

For those unfamiliar with her work on hyper-controlling parenting (using that adjective as value-neutrally as possible), it’s ruffled our feathers before. And her new book on success – with its threefold foundation of superiority, insecurity, and impulse control – promises to do so again, ht ER:

Some have denounced the book as racist. This loaded term is often bandied about in discussions about culture and achievement. Yet to point out the material success of Mormons in the United States is clearly not racist. Mormons represent just 1.7 per cent of the US population but they are disproportionately represented in the higher levels of business and politics in the country (Mitt Romney is perhaps their best-known representative). When the subject is Jews or African Americans, people get nervous. However, to talk about sociological differences is precisely the opposite of the biological racism that was prevalent in the 20th century. The book’s point is that it is cultural, not genetic, factors that lead to success…

The three determinants of success are curious, if rather crass, subjects of speculation. The superiority complex is familiar to historians. The British empire was shaped by it; no class in history has been as self-confident as the late-Victorian imperial administrator…

The last chapter of The Triple Package addresses the favourite subject of all Americans: the United States of America. The authors somewhat naively call for the US to recover its triple package, to ensure economic dominance. Despite the range and diversity of the ethnic groups described, the book is intensely self-regarding. It remains firmly in the “America the Beautiful” genre.

Though parochial, Chua and Rubenfeld’s argument is enjoyable and timely. After the financial crisis – and with rising material inequality – discussions about the cultural roots of economic success are necessary. The Triple Package may be superficial but the issues it raises are serious. They will no doubt generate more controversy and impassioned debate in the years ahead.

A few slight objections naturally arise: (1) Is this a Malcolm-Galdwell-ized version of Weber?; (2) the British Empire’s economic success was indeed underpinned in part by a superiority complex, but aren’t there non-economic costs there (cue Achebe et al)?; (3) is our superiority complex and insecurity as a nation really lacking?; (4) is it worth trying to develop those characteristics in America, even when it makes us more belligerent and/or anxious/depressed?; and (5) could we re-discover those traits even if we tried? It’s probably not worth arguing about, but from the limited New Statesman review above, the book seems likely to inspire within this blogger a potent cocktail, of, well, superiority mingled with insecurity – and critically, impulse control.

2. Also from New Statesman, John Gray reviews two recently published books (Watson and Eagleton) concerning the “death of God” idea. While we don’t really like picking big philosophical fights on this site, it’s always nice when there’s an opportunity to briefly point out that Dawkins and many of the “new atheists” are about as adroit in philosophy of religion as I would be in Dawkins’s lab. Once that’s out of the way, better and more interesting arguments for atheism can be considered, and there’s even space for interesting dialogue about the state of belief in the world. And for all of the above, look no further than the likes of Gray and Eagleton, ht DZ:

Today’s atheists cultivate a broad ignorance of the history of the ideas they fervently preach, and there are many reasons why they might prefer that the 19th-century German thinker be consigned to the memory hole. With few exceptions, contemporary atheists are earnest and militant liberals. Awkwardly, Nietzsche pointed out that liberal values derive from Jewish and Christian monotheism, and rejected these values for that very reason. There is no basis – whether in logic or history – for the prevailing notion that atheism and liberalism go together. Illustrating this fact, Nietzsche can only be an embarrassment for atheists today. Worse, they can’t help dimly suspecting they embody precisely the kind of pious freethinker that Nietzsche despised and mocked: loud in their mawkish reverence for humanity, and stridently censorious of any criticism of liberal hopes…

As Eagleton puts it, “The autonomous, self-determining Superman is yet another piece of counterfeit theology.” Aiming to save the sense of tragedy, Nietzsche ended up producing another anti-tragic faith: a hyperbolic version of humanism…

Reared on a Christian hope of redemption (he was, after all, the son of a Lutheran minister), Nietzsche was unable, finally, to accept a tragic sense of life of the kind he tried to retrieve in his early work. Yet his critique of liberal rationalism remains as forceful as ever. As he argued with masterful irony, the belief that the world can be made fully intelligible is an article of faith: a metaphysical wager, rather than a premise of rational inquiry. It is a thought our pious unbelievers are unwilling to allow. The pivotal modern critic of religion, Friedrich Nietzsche will continue to be the ghost at the atheist feast.

For those interested in Eagleton on religion, he has a forthcoming book under the working title, I assume, “Hope Without Optimism“, in which a slightly Marxist reading of Christian eschatology (history’s victims being revealed as playing an ultimately redemptive role in the Mind of God at the end of time) plays a significant role.

3. Continuing in an anthropological current, with a slight callback to Chua, we turn to a fascinating article, by LSE anthropologist David Graeber, at The Baffler examining animal play, ht MS:

Despite all this, those who do look into the matter are invariably forced to the conclusion that play does exist across the animal universe. And exists not just among such notoriously frivolous creatures as monkeys, dolphins, or puppies, but among such unlikely species as frogs, minnows, salamanders, fiddler crabs, and yes, even ants—which not only engage in frivolous activities as individuals, but also have been observed since the nineteenth century to arrange mock-wars, apparently just for the fun of it.

Why do animals play? Well, why shouldn’t they? The real question is: Why does the existence of action carried out for the sheer pleasure of acting, the exertion of powers for the sheer pleasure of exerting them, strike us as mysterious? What does it tell us about ourselves that we instinctively assume that it is?…

Herbert Spencer himself had no problem with the idea of animal play as purposeless, a mere enjoyment of surplus energy. Just as a successful industrialist or salesman could go home and play a nice game of cribbage or polo, why should those animals that succeeded in the struggle for existence not also have a bit of fun? But in the new full-blown capitalist version of evolution, where the drive for accumulation had no limits, life was no longer an end in itself, but a mere instrument for the propagation of DNA sequences—and so the very existence of play was something of a scandal.

Let us imagine a principle. Call it a principle of freedom—or, since Latinate constructions tend to carry more weight in such matters, call it a principle of ludic freedom. Let us imagine it to hold that the free exercise of an entity’s most complex powers or capacities will, under certain circumstances at least, tend to become an end in itself. It would obviously not be the only principle active in nature. Others pull other ways. But if nothing else, it would help explain what we actually observe, such as why, despite the second law of thermodynamics, the universe seems to be getting more, rather than less, complex. Evolutionary psychologists claim they can explain—as the title of one recent book has it—“why sex is fun.” What they can’t explain is why fun is fun.

There’s more, and it’s an extremely interesting article, but for me the takeaway was the suggestion that, beyond modern assumptions of a will to power and self-perpetuation and survival of the fittest, there may be a remainder – cooperation, sociability, fun – exercising our talents and faculties not for advantage necessarily, but partly just because those faculties are human and good and, well, fun. From our perspective, the main problem with a totalizing neo-Darwinist / capitalist / social Darwinist anthropology is that it relegates all human action to the sphere of the instrumental – “I do this in order to…” From that perspective, everything functions as, well, a law. Something that is an end in itself, however, is the domain of spontaneity and grace. Theologically inclined readers may notice that Graeber isn’t too far away from reverse-engineering an ancient Greek link between leisure and contemplation, which has underpinned much of Christian teleology. Instrumental love versus love for something that is an end in itself, etc. Keeping this remainder of play/contemplation intact seems a crucial condition for the persistence or revival of Christianity.

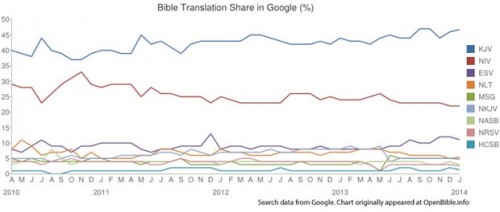

4. To lighten things a bit, historian Mark Noll presents a new study on which Bible translations are most used today. The results are a little surprising, ht ER:

The 55 percent who read the KJV easily outnumber the 19 percent who read the New International Version (NIV). And the percentages drop into the single digits for competitors such as the New Revised Standard Version, New America Bible, and the Living Bible…

The KJV also received almost 45 percent of the Bible translation-related searches on Google, compared with almost 24 percent for the NIV, according to Bible Gateway’s Stephen Smith.

In fact, searches for the KJV seem to be rising distinctly since 2005, while most other English translations are staying flat or are declining, according to Smith’s Google research.

I would’ve guessed about 40% NIV / 20 NRSV / 20 ESV /20 other, and I’m not quite sure how these data should modify that perception of American Christianity. Certainly worth a mention, though.

5. Continuing our discussion of regret this week, The Onion reports from Palo Alto that “No One Will Ever Stack Up to Your Eighth-Grade Boyfriend”, ht DZ:

According to a report released Tuesday by sociologists at Stanford University, there’s not a single potential partner out there who will ever be as kind, caring, or intelligent as your eighth-grade boyfriend, the first and last guy who totally “got” you and the only one you truly loved.

Noting that he made you feel things you won’t ever feel again, the report confirmed that no one else can stack up to your middle school sweetheart, Brian Boughton—the one who shared your first kiss, knew how to play the first verse and chorus of Green Day’s “Time Of Your Life” on his guitar, and also liked to read…

“The man you’re currently interested in, to take but one example, will never measure up to the boy who wrote heartfelt love notes and slipped them into your locker for you to find later,” Cheung said. “This new guy may have a lot going for him, but here’s what he doesn’t have: a Sony Discman containing the Dead Kennedys’ Frankenchrist that the two of you can cut class and listen to. Brian had that.”

“Face it, this is a pattern you will continue to experience for the rest of your life, always hoping for someone as wonderful as your eighth-grade boyfriend but always coming up short,” she continued. “No one will ever compare to him and you will never feel as special as you did in his cool basement. This is a fact.”

According to the report, while Brian long ago moved on with his life, there are still times when he looks back fondly on his youth and secretly pines for his first true love, the girlfriend he had in tenth grade.

6. The American Reader discovers “What Dostoevsky Knew About the Internet”, recalling a scene in his novella The Double in which an insecure character believes everyone in the room is examining and judging him – though really, just like him, they’re thinking mostly about their own presentation/image anxieties. It’s the best article on social media we’ve seen in a long, long time, ht WB:

It’s as if we are standing in the center of a roomful of people, but we don’t know where they’re looking, and we can’t help but feel, both excitedly and uneasily, that they may well be looking at us. Paranoid narcissism—the mixed desires and fears of being watched by unknown others—thus defines virtual society, giving rise to numerous related anxieties such as the sense of exposed insignificance and the fear of missing out. And with its self-consciously self-involved hero, who happens to suffer from all of these woes, The Double describes—and aptly explains—the experiential anxieties of modern social media…

To live so nakedly in the spotlight of your own skewed perceptions gives rise to a painful, pervasive embarrassment. You despise yourself for your public excesses and failures—oh, why did I post such an embarrassing, personal status?—and for your lack of compensating public success—oh, why did no one like that embarrassing status of mine? You wish to erase your tracks, but feel strangely nonexistent when undocumented; your mistakes remain glaringly public, but your good qualities refuse to go viral. Some kind of escape becomes necessary, and yet there is nowhere to go. You might as well be the eternally embarrassed Golyadkin, who, following his humiliation at the party, “looked as though he wanted to hide from himself, as though he were trying to run away from himself! … to be obliterated, to cease to be, to return to dust.”

Enter the double: the curated profile, the version of you that bears all your identifying information—name, clothes, job, appearance, place of birth—but whose social grace is impeccable, whose interests are noble and fascinating, whose biography is impressive yet humbly presented, whose comments are edited for maximum wit. Bound link by link to your real-world self with the ponderous chain of your Google results, trapped by your search and browser history in a fully customized cage, you cannot escape or erase your identity but must find a way to improve it. The avatars of social media—Facebook profiles, Twitter handles, and the like—embrace that burdensome mass of personal data and build on it, creating a version of self that is, if not quite an alter ego, at least an elaborately inflated one. Golyadkin’s double, who appears out of the shadows as he tries to outrun his embarrassment, is like this: physically and biographically indistinguishable from Golyadkin, but more confident, more charming, and more popular above all. Think of it as a deftly cropped, Photoshopped reflection: the image of yourself you always wanted to see. You have the same face, but every angle gets your good side.

Martin Luther would be proud, if he could understand all the Net references. Christian groups critiquing social media often act like the problem is mere overinvestment, an idol, while neglecting the central question of why we are attracted to it. In terms of a three-paragraph diagnosis, it doesn’t get much better than this, and we see the problem is so pervasive, so fundamental, that mere discipline is ineffective symptom-treatment; I’d venture to say the illness itself is well beyond our control. And there are, of course, good effects of social media alongside the damaging ones. As to which outweigh which, it’s a new enough phenomenon that the verdict is still out, and will be for a while.

7. See above for a bonus Bringing You the Gospel, the first building (“cornerstone”!) in a newly-developing Seoul district. Said the architects, “The cross as a religious symbol substitutes for an enormous bell tower and is integrated with the physical property of the building… The minimised symbol implies the internal tension of the space.” What else? Christians aren’t the best customers in restaurants, ht BJ; the best negative take (New Yorker) on the True Detective finale still leaves something to be desired, the New York Times’s James Collins offers a brilliant reflection on mortality; the A.V. Club (below) discovers a montage bringing Seinfeld’s latent existential doubt to the surface; The Onion (next down) satirizes a few Christian platitudes as a response to suffering; and for Girls fans (final video), Lena Dunham and SNL give us an offensive (and hilarious) Eden adaptation which we probably shouldn’t post.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply