“For those with ears to hear”, I suspect we have something of an opus from Mockingbird pop-culture expert Wenatchee the Hatchet. While we’ve tended to divvy up his material in the past, the three Cornetto Flavours films – Shaun of the Dead, Hot Fuzz, and The World’s End (recently newly-released in a box set!) just have too much perfection to separate. Bring the noise!

Now that the Blood and Ice Cream trilogy of Edgar Wright and Simon Pegg has reached its conclusion in The World’s End, it would be impossible to sum them up without a nod to Simon Pegg’s axiom that “you should always play losers because people love losers. The minute you threaten any kind of success, you’re on the edge of being derided.” Indeed, the Three Flavours Cornetto Trilogy, or Blood and Ice Cream Trilogy, examines different sorts of losers making their way in the world.

Now that the Blood and Ice Cream trilogy of Edgar Wright and Simon Pegg has reached its conclusion in The World’s End, it would be impossible to sum them up without a nod to Simon Pegg’s axiom that “you should always play losers because people love losers. The minute you threaten any kind of success, you’re on the edge of being derided.” Indeed, the Three Flavours Cornetto Trilogy, or Blood and Ice Cream Trilogy, examines different sorts of losers making their way in the world.

Simon Pegg’s losers in Shaun of the Dead (2004), Hot Fuzz (2007) and The World’s End (2013) are losers with distinct flavors that are not merely the Cornetto flavors. They are losers who are not completely outside a shot at “redemption”, first of all. Second, they are losers with something in common, what some reviewers have called the “kidult”: the physically adult male who never transitions into an emotionally and socially adult life. They have all failed, in various ways, at being what society calls a man. There are different flavors of failure, and we’re treated to ways in which males can fail to be men in their 20s, 30s and 40s respectively. That’s the simple life-stage map through which we can see Wright and Pegg explore the flavors of male failure, and what a shot at “redemption” might look like. We’ll see that it isn’t just Simon Pegg’s characters who reveal the flavors of failure but all the essential male characters throughout Edgar Wright and Simon Pegg’s trilogy.

SHAUN OF THE DEAD

So let’s start with Shaun in 2004’s Shaun of the Dead. Shaun is a 29-year old man who has never truly embraced the ambitions and concerns of adult life. His girlfriend Liz feels stuck in a boring, ritualized relationship that doesn’t seem to go anywhere. Her proposed solution is to vary the rhythm of life, while her friends simply think Shaun is unworthy of her. Shaun’s friends, meanwhile, tell him that his friendship with Ed (Nick Frost) is a tether that prevents him from ever properly growing up. Ed’s lazy gamer personality is perhaps the only thing in the film that almost, by contrast, makes Shaun seem adult.

In every other respect, Shaun’s life is marked by a failure to achieve anything. He works at a dead-end job, has a relationship with Liz characterized by exasperating inertia, and has been largely estranged from his parents since his mother remarried in the wake of his father’s death. As the first act shows in detail, Shaun’s life is practically a living death (!), and both he and the London society he is part of are dead on their feet…so much so that they don’t initially notice a zombie apocalypse breaking out in their midst!

Both literally and metaphorically, it takes a plague of zombies to shock Shaun into realizing how much he has to lose and how much he has taken for granted in his life. As Liz breaks up with him, Shaun realizes that she, too, will probably die in the zombie attack, along with everyone else he cares for.

Shaun, foolish and often incompetent though he is, springs into action, enlisting the help of his unwilling ex-girlfriend and disappointed friends to survive the zombie outbreak. His family and friends, including Ed, nearly all die off in the carnage that ensues. Despite his new intiative, Shaun doesn’t quite turn into the hero; his ‘master plan’ amid a zombie apocalypse is to revert to his same old patterns, taking refuge in the Winchester pub that has been the center of his existence. In the face of death, he clings to his old, ultimately unworkable life.

Shaun is still a man stuck in his familiar patterns, but what changes is that he now knows for what and whom he is willing to fight. He tragically learns in failure that the stepfather he thought he hated he loved far more than he could admit, and he discovers that his friends were right about Ed dragging him down, even in with new, life-or-death stakes. In the end, even Ed himself recognizes this, and he sacrifices himself to a zombie assault to give Shaun and Liz a chance to survive.

Shaun and Liz resign themselves to death alongside their friends and family, but at that moment the day is simply saved. We are discussing a romantic comedy with zombies rather than a straightforward horror film. Whatever Shaun’s continuing shortcomings as a man, Liz has seen that when the stakes are life and death he is desperate in his fight to save her. So in its way Shaun of the Dead is simply a standard romantic comedy in which a man finds redemption in choosing to actively love another. He just barely gets out of his 20s having made the transition from kidult to man. But, as we’ll see, it’s possible to learn the lesson of adult responsibility too well.

HOT FUZZ

In Hot Fuzz Simon Pegg plays Nicholas Angel, a man so responsible and righteous that his coworkers in the police force have him transferred. As the Chief Inspector tells him before Angel is transferred to the village of Sandford, “If we let you continue running around town you’ll continue to be exceptional and we can’t have that. You’ll put us all out of a job.” His ex-girlfriend Janine is even more pointed, telling Angel that he’s married to his job, adding, “You can’t just switch off, Nicholas, and until you find a person you care about more than your job, you never will.” Where Shaun lost his girlfriend through being an underachieving slacker, Nicholas loses his girlfriend by being so over-committed to his work he skipped the funeral of her father.

In Hot Fuzz Simon Pegg plays Nicholas Angel, a man so responsible and righteous that his coworkers in the police force have him transferred. As the Chief Inspector tells him before Angel is transferred to the village of Sandford, “If we let you continue running around town you’ll continue to be exceptional and we can’t have that. You’ll put us all out of a job.” His ex-girlfriend Janine is even more pointed, telling Angel that he’s married to his job, adding, “You can’t just switch off, Nicholas, and until you find a person you care about more than your job, you never will.” Where Shaun lost his girlfriend through being an underachieving slacker, Nicholas loses his girlfriend by being so over-committed to his work he skipped the funeral of her father.

So Angel is happily dispatched by London’s Chief Inspector to Sandford, a village in the middle of nowhere. As soon as Angel arrives, we see him obsessively patrol the streets, carding minors consuming alcohol and emptying the local pub of most of its underage clientele before he’s even started his first official day on the job. He arrives at the police station appalled to discover that among the drunks and minors he has arrested the night before is a police officer, Danny Butterman (Nick Frost), the son of the village Police Chief Frank Butterman (Jim Broadbent).

Undeterred, Sgt. Angel begins to instruct the Sandford police force and the villagers on how police work consists of “procedural correctness in the execution of unquestionable moral authority.” Angel is nothing if not an embodiment of the Law, and he is steadily and increasingly appalled at the ignorance, graft and nepotism of the village police force under Frank Butterman’s leadership.

But Nicholas Angel also finds himself befriending Danny Butterman, despite Danny’s laziness and incompetence as an officer. Danny is able to offer Nicholas a friendship that finally lets him “switch off” in the form of watching action movies. They turn out to share something else in common; both men were inspired to become enforcers of the law by relatives. Nicholas was inspired to be a police officer by his Uncle Derek, who turned out to be a corrupt cop selling illegal drugs to children. Nicholas tells Danny, “I had to prove to myself that the law could be proper and righteous and for the good of humankind.” However imperfect its enforcers are, Nicholas has to believe that the law itself can be utterly good.

As we know from countless horror and action movies, the quaintest, quietest and prettiest village is often where the most deceit and carnage happens. Before long Angel discovers there are murders afoot, and the incompetent and impudently lazy police force, such as it is, is completely uninterested in the phenomenal accident rate within their town. The only cop willing to give any credence to Angel’s conspiracy theory is Danny, the laziest and least engaged officer on the force. But what Danny lacks in initiative or a realistic understanding of police work, he compensates for in his intimate knowledge of everyone in the village. Where in the first film Nick Frost’s character held Simon Pegg’s character back, in the second film the two literally can’t live without each other’s help and example. Their extremities become balanced through friendship.

When Angel discovers the true nature of the murders in the village, he discover the one ultimately behind the murderous conspiracy is none other than Danny’s father, Frank Butterman, who descended into madness after his wife Irene killed herself when Sandford failed to win Village of the Year a while back. It turns out that both Nicholas Angel and Danny Butterman were inspired to become cops through relatives who have turned out to be hopelessly corrupt and self-serving in their abuse of power and procedure. Sandford’s city fathers and mothers, in their eagerness to present the image of the perfect little community, end up murdering everyone who falls short of perfection on even the most trivial details, such as an annoying laugh. Angel is confronted in a group manifestation of his own sin, a commitment to proper appearance and procedure that has come at the expense of empathy and humanity.

But this, too, is a comedy, and Angel is redeemed from a heartless enforcement of the law through the friendship extended to him by Danny. Danny for his part, finds in Angel not only friendship but the opportunity to be the kind of cop he has fantasized about being. In the first film, Nick Frost’s character sacrifices himself to let Simon Pegg’s character move forward in life; in the second, neither Pegg’s nor Frost’s characters can survive without each other. In the third film we’ll see that the pendulum reaches the end of its swing and that it is Simon Pegg’s character whom Nick Frost’s character must drag forward, kicking and screaming, into the light.

THE WORLD’S END

Nearly every cinematic trilogy could be said to end in disappointment at some level. Fittingly, the inevitability and pervasiveness of failure and disappointment as the hallmark of humanity itself is the theme of The World’s End.

Nearly every cinematic trilogy could be said to end in disappointment at some level. Fittingly, the inevitability and pervasiveness of failure and disappointment as the hallmark of humanity itself is the theme of The World’s End.

In this final film, Simon Pegg plays a man who has not merely failed to integrate into “normal” adult life, but who also is an alcoholic in a last, desperate effort to relive the glory days of his drunken teens.

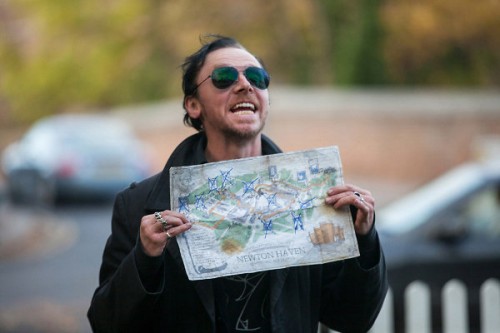

Pegg plays the alcoholic Gary King, entering his 40s and reminiscing in an AA meeting about an epic pub crawl he tried to complete with high school friends twenty years earlier. All of his friends have since gone on to be bankers or real estate agents, but to Simon Pegg’s Gary King, he is still the king, the leader of the pack. He determines to go back to his four friends to complete The Golden Mile, the dozen-pub juggernaut of drink he failed to finish decades earlier. Though all his friends, most of all his estranged friend Andy (Nick Frost, again) think the idea is terrible, they all reluctantly consent through a mixture of pity and sentiment. Not least because they’ve been duped by Gary into thinking that his mother has recently died.

The Golden Mile begins inauspiciously, with only Gary enjoying himself. When his friends bluntly confront him about his failures, Gary sneers, “Yeah, you’ve got your houses and your cars and your wives and your job security. But you don’t have what I have. Freedom. You’re all slaves and I’m free to do what I want any old time.” In his enslavement to drink, Gary nonetheless considers himself freer than his old friends, who have been able to put the bottle behind them.

In the aftermath of this confrontation, Gary and his friends end up in a brawl with homicidal robots. As they end up conversing with the robots, they are told that the word “robot” is a derived from an old Czech word “robotnik”, meaning “slave”. And yet these robots deny being either robots or slaves. Gary and his friends begin calling these things blanks. The friends begin to realize that the creeping uniformity of their old hometown doesn’t just mean they can’t go home again; something worse is happening. A network of replicant robots has replaced nearly all the citizens of Newton Haven. The blanks, as Gary calls them, look and talk and act more or less the same as their flesh-and-blood forebears, and are even improved. In a village full of blank robot replicas of those who once lived, how can you tell who is truly human?

The answer is in the wounds and scars and character flaws that simply don’t improve with age. As Gary and his friend Andy get closer to the truth about the blank army and its master, they confront The Network behind the robot assimilation of Earth. The Network is not interested in invasion so much as merging humanity into itself. The Network offers all of humanity a chance to evolve into a new glorified state of consciousness, eternal robotic existence free of the shackles of flesh and blood. Gary and Andy are offered to voluntarily join the Network, and the two friends refuse. Andy declares, “… we are more belligerent, more stubborn, and more idiotic than you can possibly imagine.”

Joined by a late-arriving Steve, Gary and Andy drunkenly rant against The Network until it gives up in despair. The remorseless drunk turns into the great preacher of human potential by championing its opposite. He goes further to argue that what makes us truly human are the irreversibly stupid decisions and ineradicable weaknesses we never completely overcome, and that this is what real humanity is, not the robotic, fleshless perfection The Network promises. Humanity, as it is, ends up being saved by a drunken ranter quoting silly pop songs instead of great philosophers or writers, and humanity is saved from assimilation into an alien entity not by its greatness, but by its foolishness. As it departs, The Network obliterates 21st century technology, taking back the technological gifts it had given humanity and boasted about to Gary, Andy and Steve. As Andy narrates the coda he sits in front of a sign that says, “To err is human, to forgive divine.”

There are few trilogies in cinema that can’t be said to end without its disappointments. Wright and Pegg are savvy enough as storytellers to make this anxiety and expectation the point of the trilogy’s final film. This self-aware decision to make failure and the passage of time so central to a science-fiction send-up may explain why critics seem more warm and receptive to The World’s End than general audiences (or at least that’s the gap reflected over at Rotten Tomatoes). Like Gary King, we know we may be disappointed by what we’re about to see and hear, and yet we may well end up going along anyway. Gary King’s lament is that in his teens he felt invincible, like there was nothing he couldn’t deal with and after twenty years’ time he discovered that was all a lie. If Shaun of the Dead played with individual failure and Hot Fuzz examined failure in community, The World’s End explores the failure of generations and ultimately of the entire human race.

Informally, friends tell me they find the newest film disappointing, though most of them who have seen it still like it overall. It’s as though Simon Pegg’s determination to play losers has become meta, with audiences wanting to like this newest movie more than they do in some cases. For a trilogy that has focused so intently on men who keep letting you down no matter how much you sincerely like them, there’s a paradoxical perfection in The World’s End as the end to the Ice Cream and Blood trilogy.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply