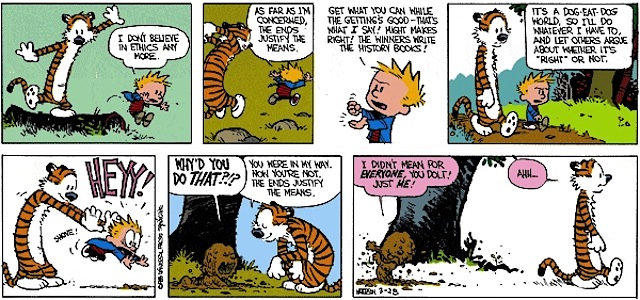

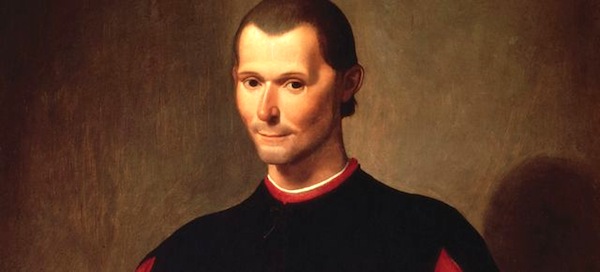

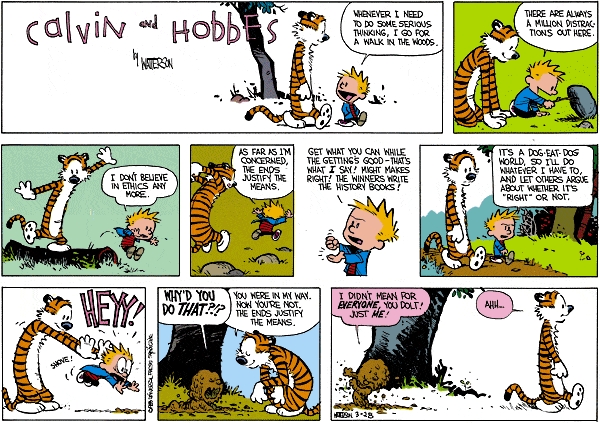

I’ve been reading Niccolo Machiavelli lately, the brilliant Renaissance-era adviser of princes, and have found myself much more attracted to him than I’d expected. To say that his reputation precedes him is an understatement–very few last names become as frequently dropped modifiers as ‘Machiavellian’, which usually refers to someone who believes that ends justify means (a statement often misattributed to the Florentine) and endorses cruelty, opportunism, and cold manipulation. But there’s a gap between Machiavelli’s reputation and his writings, and I think that gap can speak to us.

I’ve been reading Niccolo Machiavelli lately, the brilliant Renaissance-era adviser of princes, and have found myself much more attracted to him than I’d expected. To say that his reputation precedes him is an understatement–very few last names become as frequently dropped modifiers as ‘Machiavellian’, which usually refers to someone who believes that ends justify means (a statement often misattributed to the Florentine) and endorses cruelty, opportunism, and cold manipulation. But there’s a gap between Machiavelli’s reputation and his writings, and I think that gap can speak to us.

I won’t attempt (and don’t think there’s much warrant for) a revisionist reading of Machiavelli, but the great University of London historian Quentin Skinner takes a few interesting steps in that direction. First, for the context Machiavelli was writing in, we see the Italian humanists extolling man’s self-development in virtue and, in the process, presenting

an almost Pelagian departure from the prevailing assumptions of Augustinian Christianity… The truth is that, [for Augustine] if men prove capable of achieving greatness, this is only because God has willed it.

Renaissance beliefs, on the contrary, viewed humans as vying with capricious Fortune (replacing Providence), with the opportunity to prevail of their own strength and agency. Again, in Skinner’s view:

This emphasis on man’s creative powers came to be one of the most influential as well as characteristic doctrines of Renaissance humanism. It first of all helped to foster a new interest in the human personality. It came to seem possible for man to use his freedom to become the architect and explorer of his own character.

If Skinner’s Renaissance account is to be trusted, then being the architects of our character first emerged, in the modern world, in part from a rejection of Augustinian Providence. And Skinner goes on to trace the emergence, from the above optimism, of a ascribing a moral value to work, as well as other conceptual innovations facilitated by throwing off Augustine’s gloomy yoke. But what concerns us here is the idea that someone can develop himself (gender-inclusive language lamentably anachronistic here) into a model of virtue. As widely participatory Republican civic life in Northern Italy gradually gave way to one-man rulerships, the figure of the Prince became the model for virtuous development.

The problem with Machiavelli was that he just couldn’t quite buy into it. In one of the few prominent appropriations of St. Paul from this period (Rm 7), Machiavelli wrote,

But, it being my intention to write a thing which shall be useful to him who apprehends it, it appears to me more appropriate to follow up the real truth of the matter than the imagination of it; for many have pictured republics and principalities which in fact have never been known or seen, because how one lives is so far distant from how one ought to live, that he who neglects what is done for what ought to be done, sooner effects his ruin than his preservation; for a man who wishes to act entirely up to his professions of virtue soon meets with what destroys him among so much that is evil.

Hence it is necessary for a prince wishing to hold his own to know how to do wrong, and to make use of it or not according to necessity. Therefore, putting on one side imaginary things concerning a prince, and discussing those which are real, I say that all men when they are spoken of, and chiefly princes for being more highly placed, are remarkable for some of those qualities which bring them either blame or praise… And I know that every one will confess that it would be most praiseworthy in a prince to exhibit all the above qualities that are considered good; but because they can neither be entirely possessed nor observed, for human conditions do not permit it, it is necessary for him to be sufficiently prudent that he may know how to avoid the reproach of those vices which would lose him his state…

A few points come to light here – first, that the Florentine wasn’t quite an Antinomian, since he still held it as a matter of course that traditionally ‘good’ qualities are indeed preferable. His closing idea in this passage, that it’s realistic only to avoid the worst vices, forms the basis for much of his discussion of coercion, manipulation, etc.

And so I don’t follow him completely, but you have to feel some sympathy for a writer who spoke the truth about human nature in an inordinately optimistic age. Whether or not being willing to compromise when necessary, as Machiavelli advocates, is a matter of serious debate, but by no means does his position here (especially with regard to its context) make him a particularly ‘Machiavellian’ figure, as we use the term.

The message that ‘human conditions do not permit it’ never sells, and the second people got the wealth, education, and conceptual framework (and relief from the Black Death) allowing them to jettison Augustine’s grim views on agency, they did. I’m simplifying, of course, but the lack of moral nuance and resistance to pessimism about our own nature is persistent. At the least, Machiavelli told the truth, knowing that pragmatic, rather than moral, how-to’s was the only kind of instruction we receive – a profound willingness to live in reality. Of course, we can’t give the guy too much credit: perhaps he’s not so much resurrecting Christian anthropology as he is using his anthropological insight as an anchor for his pragmatism.

The message that we should balance our self-justifying, reality-avoiding attention to the ‘ought’ with an honest regard for the ‘is’ often gets charged with amoralism or anti-nomianism. But shedding the pretensions of the ego-boosting ‘ought’ preoccupation can be quite profitable politically (when you apply the insight to other people), and it begins to look a lot like repentance, what in AA terminology is called ‘hugging the cactus’, when applied to oneself. At particularly optimistic periods in history, we hate the former; we always hate the latter.

Unfortunately, the need to pass judgment upon such honesty often says more about ourselves than it does our target (Mt 7:1, 3-5). Ironically, to say that taking our focus – if only for a moment – off the ‘oughts’ of life risks amoralism is to make the only true statement of despair possible within a still-Christian framework. The way the pariahs see it, we’re amoral already – and that’s a fact we must break through to the ‘is’ of our fallenness to cope with.

COMMENTS

2 responses to “Doing Wrong Well: Augustine and Machiavellian Anthropology”

Leave a Reply

You might consider that Machiavelli was compelled to cloak his real motive for writing The Prince by writing a satirical commentary, intended to warn others of what can happen when a ruler follows the machiavellian method in governing. His work would never have been published in his Medici-governed Florence if he had revealed his true feelings. He had previously been arrested by the Medici ruler for his republican anti-dictatorial tendencies, and tortured on the rack for them. There was no other way to publish his warning, without disguising it in machiavellian terms.

Thanks for that interpretation. As far as I’m aware, you’re right about the persistence of his republican feelings. The man himself was something of an opportunist, though; the Prince was also an attempt, as I understand it, to ingratiate himself with the Medicis after they regained control of the city (there’s some self-ingratiation to them near the end). And yet – though the republic was considered ideal, he may have thought it unrealizable, and thus devoted himself to making the city thrive as-is; perhaps the realist in him knows he can’t re-engineer Florence’s earlier state.