In celebration of the American release of Unapologetic: Why, Despite Everything, Christianity Can Still Make Surprising Emotional Sense, we sat down (via Skype) with Francis Spufford to talk about his book, its American release, and the “Yeshua” chapter that still has us reeling. We talked about other things, too; like the problem of human emotion, like hipster irony and David Foster Wallace, like the “cruel optimism” of the world we live in, and Spufford’s own take on the Good Samaritan story.

For the full interview, though, you might just have to wait until for our first issue of our first ever Mockingbird quarterly magazine, due for release in the new year! More on this later but, until then, here’s an opportunity to go out and buy a copy.

Mockingbird: If you don’t mind talking about the Yeshua chapter? What do people think about Jesus today? And what are people not hearing about Jesus today, that they should be hearing?

Francis Spufford: Disastrous misapprehensions of Jesus: Okay. Again, I’m going to end up being more culturally specific than I know, given that I’m going to speak to the British end of this. What we’ve got for sure are a number of default stereotypes, all of which are various reasons not to take him seriously. There is the gentle-Jesus-meek-and-mild, the guy often pictured with sheep, that sort of looks like a sheep as well. The one with the tea-towel on his head, and the ringlets; he is kind of deeply culturally faded around here, and you can see it as no reason to pay attention to him.

There are little bits of Jesus-Christ-Superstar, kind of “Rockin’ Jesus,” and very obviously the actual content of what he says doesn’t fit the format, so since the whole pitch was sort of for his coolness, he’s just not that cool. He isn’t. He suffers from the “Christian Rock” problem. And you’d be on stronger grounds to engage in a little bit of cultural criticism about what exactly was coded into the idea of cool there that he is failing to be, but that aside, every now and again, you get Urban-Guerilla-Jesus-as-Ché. But that, too, again, is the way in which he appears to date himself. You say that he can be translated into this world now because “he’s a radical,” because of this world’s “radical” demands, but there’s only the residue left, so really it’s only a kind of pre-modern defect of the guy that was expressed in religious terms in the first place, so we’ll take the cause, whatever we project it being, and we’ll leave the guy behind.

There’s also, what we don’t tend to get here, very much, is, you get Authoritarian-Jesus, but he’s pretty much a Catholic phenomenon around here. Pope Benedict’s kind of Authority-Figure-Jesus who has 17 Important Things He Wants To Tell You about Personal Behavior and since he appears to be an 80-year-old German as he speaks, he too, is kind of hard to believe ever was a 33-year-old guy in 1st century Palestine.

M: Do you get “Bad Ass Jesus”? Like, “Jesus was a man…”

FS: No. I was just coming to that. It’s because faith has lost its grip on the kind of manly, sports-coaching bits of popular culture in Britain. We don’t have Jesus-is-my-Copilot. We don’t have Jesus-the-Athlete. He’s calls into question the value of winning, and then, in some very real sense, tells everyone that everyone has won as well. That’d really be no use at all. We don’t have CEO Jesus, for the same reason of the pop-cultural tide going out. We don’t have the versions which have Jesus as God’s high-up VP of this This Worldly Affairs.

FS: No. I was just coming to that. It’s because faith has lost its grip on the kind of manly, sports-coaching bits of popular culture in Britain. We don’t have Jesus-is-my-Copilot. We don’t have Jesus-the-Athlete. He’s calls into question the value of winning, and then, in some very real sense, tells everyone that everyone has won as well. That’d really be no use at all. We don’t have CEO Jesus, for the same reason of the pop-cultural tide going out. We don’t have the versions which have Jesus as God’s high-up VP of this This Worldly Affairs.

In some ways, I kind of regret it. There’s a weakness in being freed from these kinds of illusions. It’s because we don’t even have the ground on which these illusions could be propped. And it’s easier, in some ways, to get from an illusion into a reality, than it is to get from a complete absence to a reality. So in some respects you should be glad that you still got biceps Jesus and Wrestling-Coach-Jesus; because someone who eventually goes into the New Testament looking for Wrestling-Coach-Jesus is going to find some other stuff in there. And it can detain you. And before you know, you’re on deeply treacherous ground, and you’ve been moved by all sorts of deeply unmanly shit.

M: In your first chapter, you talk about your daughter and the kind of “meh” response she will receive for having grown up in a Christian household. It’s not just these different Jesuses, but the irrelevance of Christian life in general today.

FS: It’s embarrassing. It’s unnecessarily and embarrassingly earnest. It’s kind of making a fuss about something in public when no one can see any reason for it. It’s slightly crazed and not very funny.

M: So not the meek, not the cool, not the Ché, not the ironic, so then, what are we missing? Who is Jesus?

FS: We’re missing the open door to a generosity which thinks that law is the very beginning of what human beings need, where calling it radical is too small. You could call it conservative and it would make just as much sense, and you would still slough it off like a skin and leave it way behind. He is somebody. He is love without cost controls engaged. He is what it looks like to love deliberately without self-protection. And in this case, both to pay the ordinary human price for doing that, and having the resources of the Creator of all things behind it. Immensely strong and immensely weak, alpha and omega. I don’t find images of kings and majesty very helpful here. But I do find the oceanic images, to do with generosity and love beyond all human rationing and counting, helpful.

I’m working very hard not to quote myself here, if you know what I mean. The bits in the book, the stuff in the Yeshua chapter, the crucifixion bit, the series of “I ams,” are not mine. They are my phrasings of 2,000 years of trying to do justice to that state of unimaginable flow, redemptive flow, through the narrow doorway of a dying man. I’ve gone through phases throughout my own Christian history during which what Jesus was seems to loom larger than what He did, and other times what he says seems to loom larger as well. But teacher and redeemer and actor (modeler) of the way he is trying to encourage, they aren’t any more separable than thoughts and feelings. They kind of flow together into the same, ungovernable pool there.

It’s interesting, isn’t it? It’s a register of what we find our pressing cultural dangers are as Christians, what we want to emphasize. If our danger is feeling that we might be offered a sort of Authoritarian human-scale Jesus, who’s only a teacher of restrictive virtues, we therefore settle down all too easily into being the embodiment of church as social glue—and then what we want is to kind of push for the kind of Law-Breaking-Boundaryless aspect of Him. If, on the other hand, we are dealing with those bits of our culture which think it’s doing generosity but is, in fact, just doing vast lukewarm “I-really-can’t-be-fucked-to-comment-on-that”, at that point what you start to notice about Jesus is that he’s got some damn sharp critical edges, as well. It’s not a sort of “anything goes” doctrine at all—it’s an “anything can be mended” doctrine. It comes first with an understanding of what it means to break stuff in the first place, so that it can be mended. It’s very clear-eyed. He’s a moralist, damnit! He’s not a hippy! He’s just also not not a hippy! Do you see what I mean? He’s not not a king either!

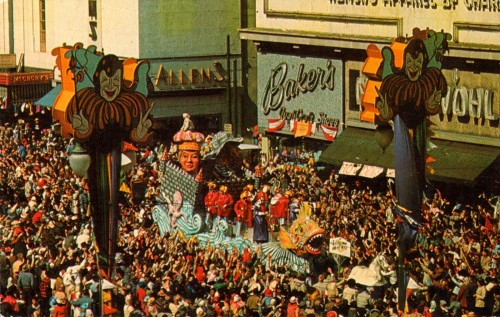

M: Right, that’s the King’s Parade you describe in “Yeshua.” The entrance of the king is also a circus, it’s a kind of king, but it also looks like—

FS: A parody of a king! Right. And you cannot dismiss either aspect there. Which is true of a lot of the Incarnation. It’s an action by God within the terms of human history. It doesn’t fit very well, and at the same time it is in within the terms of human history. It’s deliberately athwart to the way that human history goes, but it’s still—he’s a man acting. So it’s not an illusion, to say “He looks a bit like a king,” but then you also have to say, “Well, and then he doesn’t.”

There are dangers and temptations here as well. Paradox can be a very easy way of letting yourself off the hook of the tough stuff. I slightly fear the word “inclusive” when I see it, because a) it’s much too small for the kind of divine generosity we’re talking about here, and b) it can very often mean we are too nice to ever give ourselves a hard time about anything. It doesn’t mean we should give other people a hard time, but again, the soft and fluffy marshmallow cloud of our collective self-approval, is not what the religion is about. On the other hand it shouldn’t be about hating yourself, either, but we know that.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iwEe4c2bzVo&w=600]

COMMENTS

2 responses to “Mockingbird Interviews Francis Spufford”

Leave a Reply

There is so much good in this little interview excerpt that it is a little breathtaking.

[…] movement dead. It’s not a stretch to say that Spufford’s fantastic book, Unapologetic, had something to do with the downfall. Another contributing factor? The arrogance of it all, and not just because the […]