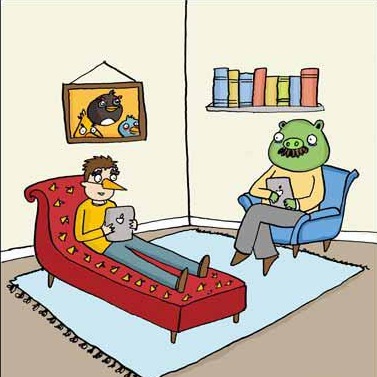

Have you been taught, by a small child, how to play Angry Birds? Were you amazed–kind of creeped out?–to see how they maneuvered the slingshot, how deftly they manipulated those pig structures?

The New York Times Magazine just published this from fiction writer Steve Almond, about the perils latent in the swift currents of a technological upbringing. Unlike most articles of this type, Almond isn’t retrograde. In seeing his small children carry newfangled conveniences and distractions into their household, he doesn’t call forth his own childhood as the golden age, but as the age to blame. He calls his 20s his age of “reformation,” where he read literature and began writing stories; he now takes pride in the fact that there’s no television in their house, but places himself in the simul analog et android camp. He is as skeptical of the tech-education movement as he is himself. While he has spent nearly two decades attempting to deny himself the new “pixelated enticements” for the sake of his own sanity, he finds himself unsuccessful, manipulating trackpads with his contemporaries, just “slower on the uptake”.

Still his observations are poignant. To believe that eyes fixated upon a smoothly directable, quickly responsive blue screen will not, in some way, diminish our ability to be family, to, as Marilynne Robinson describes it, “shelter and nourish and humanize one another.” This is as true for a parent in line at BestBuy as it is for his young child coming home with a Leapster. Probably more so. In this way technology isn’t just making us attention-deficit candidates–Almond points not only to the use of technology to “hold tedium at bay,” but also the increasing need for it to fill our neediness for love and value. Almond uses his neighborhood primary school as an example, where the entire student body is receiving a fleet of iPads for educational purposes. Take it away, Steve (ht DMZ):

It’s not because I’m a cranky Luddite. I swear. I recognize that iPads, if introduced with a clear plan, and properly supervised, can improve learning and allow students to work at their own pace. Those are big ifs in an era of overcrowded classrooms. But my hunch is that our school will do a fine job. We live in a town filled with talented educators and concerned parents.

Frankly, I find it more disturbing that a brand-name product is being elevated to the status of mandatory school supply. I also worry that iPads might transform the classroom from a social environment into an educational subway car, each student fixated on his or her personalized educational gadget.

But beneath this fretting is a more fundamental beef: the school system, without meaning to, is subverting my parenting, in particular my fitful efforts to regulate my children’s exposure to screens. These efforts arise directly from my own tortured history as a digital pioneer, and the war still raging within me between harnessing the dazzling gifts of technology versus fighting to preserve the slower, less convenient pleasures of the analog world.

What I’m experiencing is, in essence, a generational reckoning, that queasy moment when those of us whose impatient desires drove the tech revolution must face the inheritors of this enthusiasm: our children.

It will probably come as no surprise that I’m one of those annoying people fond of boasting that I don’t own a TV. It makes me feel noble to mention this — I am feeling noble right now! — as if I’m taking a brave stand against the vulgar superficiality of the age. What I mention less frequently is the reason I don’t own a TV: because I would watch it constantly.

…Midway through my 20s I underwent a reformation. I began reading, then writing, literary fiction. It quickly became apparent that the quality of my work rose in direct proportion to my ability filter out distractions. I’ve spent the past two decades struggling to resist the endless pixelated enticements intended to capture and monetize every spare second of human attention.

Has this campaign succeeded? Not really. I’ve just been a bit slower on the uptake than my contemporaries. But even without a TV or smartphones, our household can feel dominated by computers, especially because I and my wife (also a writer) work at home. We stare into our screens for hours at a stretch, working and just as often distracting ourselves from work.

Our children not only pick up on this fraught dynamic; they re-enact it. We ostensibly limit Josie (age 6) and Judah (age 4) to 45 minutes of screen time per day. But they find ways to get more: hunkering down with the videos Josie takes on her camera, sweet-talking the grandparents and so on. The temptations have only multiplied as they move out into a world saturated by technology.

Consider an incident that has come to be known in my household as the Leapster Imbroglio. For those unfamiliar with the Leapster, it is a “learning game system” aimed at 4-to-9-year-olds. Josie has wanted one for more than a year. “My two best friends have a Leapster and I don’t,” she sobbed to her mother recently. “I feel like a loser!”

My wife was practically in tears as she related this episode to me. It struck me as terribly sad that an electronic device had become, in our daughter’s mind, such a powerful talisman of personal worth. But even sadder was the fact that I knew, deep down, exactly how she felt.

This is the moment we live in, the one our childhoods foretold. When I see Josie clutching her grandmother’s Kindle to play Angry Birds for the 10th straight time, or I watch my son stuporously soaking up a cartoon, I’m really seeing myself as a kid — anxious, needy for love but willing to settle for electronic distraction to soothe my nerves or hold tedium at bay.

…Her own experience learning to read is a case in point. We spent a year coaxing her to try beginner books. Even with the promise of our company and encouragement, it was a tough sell. Then her teacher sent home a note about a Web site that allows kids to listen to stories, with some rudimentary animation, before reading them and taking a quiz to earn points. She has since plowed through more than 50 books.

Josie never fails to remind me that “the reading” is her least favorite part of this activity. And when she does, I feel (once again) that I’m face to face with myself as a kid: more interested in racking up points than embracing the joys of reading. What I’m lamenting isn’t that she prefers to read off a screen but that the screen alters and dilutes the imaginative experience.

It is unfair, not to mention foolish, for me to expect my 6-year-old to seek redemption in the same way I did, only at age 25. Her job is to make the same sometimes-impulsive decisions I made as a kid (and teenager and young adult). And my job is to let her learn her own lessons rather than imposing mine on her.

Still, I can’t be the only parent feeling whiplashed by the pace of technological changes, the manner in which every conceivable wonder — not just the diversions but also the curriculums and cures, the assembled beauty and wisdom of the ages — has migrated inside our portable machines. Is it really possible to hand kids these magical devices without somehow dimming their sense of wonder at the world beyond the screen?

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=91sI-JVits0&w=550]

In the course of mulling this question, I stumbled across an odd trove of videos (on YouTube, naturally) in which parents proudly record their babies operating iPads. One girl is 9 months old. Her ability to manipulate the touch screen is astonishing. But the clip is profoundly eerie. The child’s face glows like an alien as she scrolls from app to app. It’s like watching some bizarre inverse of Skinner’s box, in which the child subject is overrun by choices and stimuli. She seems agitated in the same way my kids are after “quiet time” — excited without being engaged.

As I watched her in action, I found myself wondering how a malleable brain like hers might be shaped by this odd experience of being the lord of a tiny two-dimensional universe. And whether a child exposed to such an experience routinely might later struggle to contend with the necessary frustrations and mysteries of the actual world.

I realize the human brain is a supple organ. My daughter may learn to use technology in ways I never have: to focus her attention, to stimulate her imagination, to expand her sense of possibility. And I know too that most folks view their devices as relatively harmless paths to greater efficiency and connectivity.

Because aren’t we just kidding ourselves? When we whip out our smartphones in line at the bank, 9 times out of 10 it’s because we’re jonesing for a microhit of stimulation, or that feeling of power that comes with holding a tiny universe in our fist.

The reason people turn to screens hasn’t changed much over the years. They remain mirrors that reflect a species in retreat from the burdens of modern consciousness, from boredom and isolation and helplessness.

It’s natural for children to seek out a powerful tool to banish these feelings. But the only reliable antidote to such burdens, based on my own experience, is not immersion in brighter and mightier screens but the capacity to slow our minds and pay sustained attention to the world around us. This is how all of us — whether artists or scientists or kindergartners — find beauty and meaning in the unceasing rush of experience. It’s how we develop empathy for other people, and the humility to accept our failures and keep struggling. It’s what grants my daughter the patience to wait for the cardinal who has taken to visiting the compost bin on our back porch.

I imagine the iPad Josie receives at school next year will have access to a vast archive of information and videos about cardinals, ones she’ll be able to call up and peruse instantly. But no flick of the thumb will ever make her suck in her breath as she does when, after five excruciating minutes, an actual cardinal appears on the porch railing in a flash of impossible red. I hope Josie remembers that all her life. I hope we both do.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply