This week, we get to hear all about Christianity, morality, and sanctification, from the ever-insightful Gustave Flaubert, in his fantastic story about learning to hunt as an up-and-coming medieval prince. After a series of twists, we meet Jesus Christ in a riverside hovel. Read along here.

Only the saint knows sin.

-W.P. DuBose

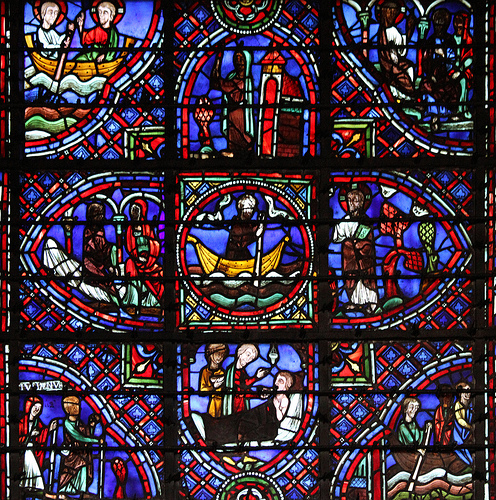

A pretentious student once asked Flannery O’Connor whether she had been influenced at all by Flaubert. She responded (once imagines in her thickest Southern drawl), “FLOW-BARE? Never heard of him.” Despite the sarcasm, his writing style, stance on faith, and meditations on how the grace of God changes someone were decisive influences on her thought. Gustave Flaubert stood as a premodern, anticipating the themes of modern literature during the nineteenth century. His Three Tales, the collection featuring this story, was his meditation on faith in a rapidly secularizing age. If we give the great twentieth-century agnostic novelists one thing, it’s got to be an accurate view of the human predicament. Flaubert addressed this predicament and the emotional plausibility of Christianity, poised as a brilliant, skeptical-bordering-on-agnostic writer with a deep nostalgia for the Christian faith. This legend is his foray into the truth and beauty of Christianity, even though he eventually laments that it is only a legend, a story “as it is given on the stained-glass window of a church in my birthplace.”

A pretentious student once asked Flannery O’Connor whether she had been influenced at all by Flaubert. She responded (once imagines in her thickest Southern drawl), “FLOW-BARE? Never heard of him.” Despite the sarcasm, his writing style, stance on faith, and meditations on how the grace of God changes someone were decisive influences on her thought. Gustave Flaubert stood as a premodern, anticipating the themes of modern literature during the nineteenth century. His Three Tales, the collection featuring this story, was his meditation on faith in a rapidly secularizing age. If we give the great twentieth-century agnostic novelists one thing, it’s got to be an accurate view of the human predicament. Flaubert addressed this predicament and the emotional plausibility of Christianity, poised as a brilliant, skeptical-bordering-on-agnostic writer with a deep nostalgia for the Christian faith. This legend is his foray into the truth and beauty of Christianity, even though he eventually laments that it is only a legend, a story “as it is given on the stained-glass window of a church in my birthplace.”

Nonetheless, Flaubert’s insights are startling. We return to the question of saintliness, and see that it can pursued in the form of glory or the form of defeat.

Julian, we learn, was brought up in a castle by two extraordinarily loving and attentive parents, who made sure that he had the best in everything, from entertainment to religious instruction to academic education. Flaubert, as a skeptic, emphasizes the quality of his upbringing and the goodness of his parents in order to reject conventional moral teaching. Even though this child has the best of everything, including biological stock (which was important to people in GF’s time) and moral education, he kills, (contra Pelagius), a mouse during church one day. We moderns could say that the superego collapsed and the id came to the fore; theology would rephrase this as the inevitable eruption of Original Sin. In this, the (initial) skeptics and (orthodox) Christianity agree: the form of glory, with respect to moral education, fails utterly. In Julian’s case, it suppresses the inner sociopath for a time, but its ultimate fruit is futility and rebellion.

…when that desire has conceived, it gives birth to sin, and that sin, when it is fully grown, gives birth to death.

James 1:15

In Sermon on the Mount terms, we could say that Julian’s killing of the mouse just for the sport of it (cf. Augustine’s pears), it reveals a character trait that condemns him every bit as much as his later rampages of violence will. We see the desire of his sin, and much of the story is about its becoming “fully grown.” He begins to hunt and kill more and more, eventually reaching the point when he no longer bothers bringing his kills home, but rather kills just for the sport of it. The moral structure of violence is such that there’s an inflictor (Julian) and a receiver (the animals). But the split between the inflictor and the victim is artificial – that is, it exists only in individual experience, not in the actual structure of the world. In the morally rooted universe of creation, all things are good, and all things mirror, to greater or lesser extent, the goodness of the Creator. The split which violence introduces exists in the mind of its subject but, ‘in the grand scheme of things’, it is violence against God’s goodness – the same goodness that marks Julian himself (Gen 1:31) – so that violence against nature is violence against his own origin and source of being (Ps 51:4 – “against you, you only, have I sinned”) and, by extension, himself (Col 1:16-17, a crucial passage here).

Flaubert understood these biblical ideas instinctively; so that Julian’s destruction of animals is ultimately a negation of his own origin and being: this is the literary and moral meaning of the curse Julian receives – “Accursed! some day, ferocious soul, thou wilt murder thy father and thy mother!”

The sting of death is sin, and the power of sin is the law.

1 Cor 15:56

Julian’s response is to flee from home and avoid any situation in which he may encounter his parents – avoid at all costs. He stops hunting, too, because he recognizes the correlation between his sociopathy toward animals and the possibility of violence to his own parents. The problem is that he cannot flee from his human nature – he carries it with him everywhere. Worse, if “the power of sin” really is “the law”, then his attempts to change his behavior actually make things worse.

Why is this? It’s because external obedience to the moral law still operates within the form and structure of glory: self-reliance, pride, achievement performance-ism, whatever you want to call it; the form of glory is opposed to genuine love and genuine change for the better. Following the rules helps him for a time, but it’s like placing a layer of brilliant white paint over a tomb – it will eventually crack. Or, in Shakespeare’s words, “murder cannot be hid long; a man’s son may, but at the length truth will out.”

Amidst his flight he grows restless; his bland moralism does nothing to arrest the growth of sin within him, and eventually it takes him over once more, and indeed gives birth to death. Unable to resist any longer, Julian’s facade cracks and he goes hunting, but he can kill nothing. This is the first place that, in James’s moral logic, sin gives birth to death: performance-ism gives birth to powerlessness, and the form of violence suddenly fails him. The animals follow him – symbols of his harrowing guilt in the way they harass him, but also embodiments of grace in that they refuse to repay him for the death he’s dispensed to them. So not only does his power fail him, but also he sees a higher reality of mercy (the animals ‘turn the other cheek’ as he’s trying to kill them), and this brings him to his knees.

But Julian, having spent too long in the world of power which moves “In appetency, on its metalled ways” (Eliot), will make a last-ditch stand against his powerlessness before he will recognize it. He rages against the beasts, against the dying of his power, and is in such a fury that he immediately kills the couple in his bed, who are his parents, given hospitality by his wife after spending years searching for him. As a sidenote, this killing is not accidental, at least not from the standpoint of moral law. He thinks his parents are his wife and another man, but it’s judgment rather than mere bad luck when he actually kills his parents. Because he does make the decision to kill his wife because she has presumably cheated on him – conquering a fickle and conditional world through self-assertion and power. But when his pursuit of power shatters his illusions of morality, the form of glory dies. He sees his sin for what it is and can no longer be self-reliant or self-assertive at all, ever. Again, we have to admire Flaubert for expressing a Christian idea so well as an outsider. Indeed, critiquing Christianity’s form of the quest for glory – which is moralism – is one of the great achievements of modern skeptical thought.

Sin has been fully formed in his attempted murder of his wife, and it has given birth to death in the murder of his parents and, perhaps more profoundly, the death of his illusions that sin can be escaped. Moralism isn’t something to be successfully pursued; true holiness must happen to a person, at least for Flaubert. To this nineteenth-century master, if Christianity does have a hope, it lies in death, in the stripping of the altar to make way for Christ’s resurrection. But we mustn’t get ahead of ourselves.

The Lord kills and brings to life; He brings down to hell and raises up; He brings low, He also exalts

1 Sam 2:6-7

Death is not the end, and death to the form of glory – with its attendant pride – is actually the beginning. Julian’s violence is self-assertion, and it cannot be overcome with moral self-assertion. His problem is the self, so the self must die, and it does. His guilt drives him into the wilderness (the proverbial heath), where he is alone, in exile, and without hope of ever changing himself from the murderer he is, and in truth, has always been. Strangely, when any hope of morality is truly abandoned, he becomes…a saint. The final moments of the story epitomize this transformation, when Julian meets the “least of these” – a vile, odorous, leprous wandering stranger – who demands everything from him. After rowing the man across a river, giving him all his food and drink, and allowing him to share his bed for warmth, Julian is shocked to discover that the vagabond is Jesus himself, and then Christ bears him straight to heaven.

…in him all things in heaven and on earth were created, things visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or powers—all things have been created through him and for him. He himself is before all things, and in him all things hold together

-Col 1:16-17

In forcefully rejecting creation, Julian rejected the Creator. But now, his embrace of death in the particular proves redemptive, as the death of James 1:15 gives way to the death of all Julian’s efforts, moral and otherwise, toward self-assertion.

Morality and immorality, success, failure, innocence, and guilt are all meaningless forms of the world unless the origin, the One in whom all things hold together, is encountered in love. Christ is above all and must, indeed can only be, first encountered in the decisive embrace of suffering. The stranger asks Julian to make his suffering Julian’s own and, precisely because Julian esteems himself nothing and is in a place of death, he can fully enter into empathy and identification with archetypal sin, archetypal death, he who was made “to be sin for us” (2 Cor 5:21). And it’s this fullness which makes Julian into a saint, because he has been emptied entirely, and thus he can be entirely filled with the compassion which, at the last, makes him inextricably cling to the Christ. The ideals of truth, goodness, beauty cannot be sought on their own, for sin hinders and enmeshes us at every step, every turn, leading unto death. Desire begets sin, sin begets death, and death – because of Christ – begets resurrection and newness of life. We cannot pursue goodness through strength, but he who holds all things together makes his weakness available, free for the taking, in the ultimately decisive embrace – and love – of weakness. If Julian’s sainthood sprung even – perhaps especially – from the depths of suffering, guilt, and deconstruction, then we can truly affirm that “all things work together for the good of those who love him.”

Morality and immorality, success, failure, innocence, and guilt are all meaningless forms of the world unless the origin, the One in whom all things hold together, is encountered in love. Christ is above all and must, indeed can only be, first encountered in the decisive embrace of suffering. The stranger asks Julian to make his suffering Julian’s own and, precisely because Julian esteems himself nothing and is in a place of death, he can fully enter into empathy and identification with archetypal sin, archetypal death, he who was made “to be sin for us” (2 Cor 5:21). And it’s this fullness which makes Julian into a saint, because he has been emptied entirely, and thus he can be entirely filled with the compassion which, at the last, makes him inextricably cling to the Christ. The ideals of truth, goodness, beauty cannot be sought on their own, for sin hinders and enmeshes us at every step, every turn, leading unto death. Desire begets sin, sin begets death, and death – because of Christ – begets resurrection and newness of life. We cannot pursue goodness through strength, but he who holds all things together makes his weakness available, free for the taking, in the ultimately decisive embrace – and love – of weakness. If Julian’s sainthood sprung even – perhaps especially – from the depths of suffering, guilt, and deconstruction, then we can truly affirm that “all things work together for the good of those who love him.”

But can we really? I can’t buy it; not fully. Flaubert longs to believe this story, stylistically swaddling the beauty of Christ in the decrepit beggar, but he distances himself at the end – “And this is the story of Saint Julian the Hospitaller, as it is given on the stained-glass window of a church in my birthplace.” I buy into the story perhaps more than Flaubert, but I cannot escape the distance from the story he so masterfully engages at the end. Most of us sinners cannot meet Christ in the place where Julian did – the total, self-emptying place of weakness. Those of us (almost all) who lack Julian’s searing blessing of divine deconstruction and resurrection must meet Christ in the place where we are – where we say, perhaps even along with a yearning and nostalgic Flaubert – “Lord, I believe; help thou my unbelief!” As beautiful as this story is, we fool ourselves in thinking we totally buy it. The reality of our predicament prevents us from fully believing, as did Julian, or from ever fully seeing the beauty of weakness, as did Julian. We identify more with Flaubert, who, from a place of honesty, was finally forced to admit his distance from the beauty and power of the story. The human tragedy is precisely this distance, and our inability to overcome it is death but, if Christ is true, so it may also be our life. We the reader encounter Christ in our weakness not in the way of St. Julian, but in the desperate cry from the place of honesty in knowing, with Flaubert, how short we fall of true belief. And yet this is where Christ meets us – not in denial, pretending to believe perfectly, or any other structures of the theology of glory – but in the confession of our weakness, in whatever area it lies. The form of the cross, for most of us, can be entered only through the admission that we do not, cannot fully embrace the way of weakness. We can only pray to cling to honesty about our distance from the ideal, and for the grace of God to overcome the distance in our hearts as He – in some true sense – already has.

Check back in two weeks for a ethics, revenge, and paternal love – “A Father’s Story” by Andre Dubus, available below:

COMMENTS

2 responses to “Short Story Wednesdays: “The Legend of St. Julian the Hospitaller” by Gustave Flaubert”

Leave a Reply

Just wanted to say this is one of the best posts I’ve seen on this site

Thank you for posting this interesting and intriguing story by Gustave Flaubert! For me, it has a special meaning and interest as I am still trying to further research on my St. Julien lineage for quite some time and, have indeed, accomplished much in the way of genealogical information on this surname (and subsequent other lines) to date. Until I had began this journey I had not realized the real magnitude of my French ancestry! My 6th. Great Grandfather, Count Pierre “Ren’e” de St. Julien (aka Julien/Julian after arriving in America to redeem a land grant from King William III (a cousin), for his military service on behalf of England for he was a rebel French Protestant Huguenot in that war…