“You ask for these special powers to achieve these heights, and now you got it and you want to give it back, but you can’t…I drove myself so much that I’m still living with some of those drives…I don’t know how to get rid of it.”

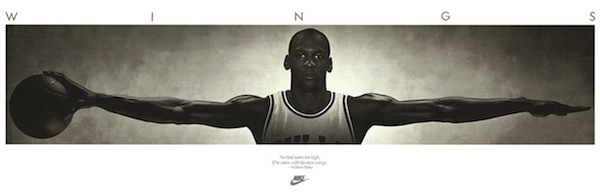

These are the words of a 50-year-old Michael Jordan, in an interview with ESPN’s Wright Thompson this past week. The name of the article ESPN released is “Jordan Has Not Left the Building: As He Turns 50, MJ Is Wondering If There Are Any More Asses to Kick.” There is an illustration of a Bulls-era Michael Jordan, in uniform on a painted pony, riding out in Western fashion into the cactus-hewn sunset. For all the irony, the article gives you the picture of a man haunted by his own achievements, a man frankly honest and saddened by the fact that he is still hungry for more, though he probably needs to buy glasses soon. He flies in a custom Gulfstream with his Jumpman logo angling off the wings, he owns an NBA team now, with the worst winning percentage in NBA history, and yet still cannot shake how badly he’d like to be on the court playing again. The article talks about this irascible drive:

This started at an early age. Jordan genuinely believed his father liked his older brother, Larry, more than he liked him, and he used that insecurity as motivation. He burned, and thought if he succeeded, he would demand an equal share of affection. His whole life has been about proving things, to the people around him, to strangers, to himself. This has been successful and spectacularly unhealthy. If the boy in those letters from Chapel Hill is gone, it is this appetite to prove — to attack and to dominate and to win — that killed him. In the many biographies written about Jordan, most notably in David Halberstam’s “Playing for Keeps,” a common word used to describe Jordan is “rage.”

Switching gears, the past week has also surfaced a cloud of suspicion over underdog Olympian Oscar Pistorius, in wake of the homicide of his girlfriend in his own home on Valentine’s Day. Rather than the comparatively slow ease with which the public was let down with Lance Armstrong, this news was a sudden bomb drop. Not only did Pistorius, like Lance, embody the athletic fantasy of obstacle-scaling achievement–he did so quite recently, and then fell (albeit the charges are not proven) in the graspable memory of his triumph.

And so the Atlantic has seen correlation with this kind of “hero’s fall” and the heroic narrative we’ve grown to expect in modern culture. Lane Wallace writes that these expectations for achievement–which exist in any realm of human life, not just sports–have created pressures for “greatness” that is uncompromisingly singular. Wallace points out, first, that this is certainly not the ways heroes have been imagined or mythologized in the past–which is something we can attest to in the biblical heroism of Abraham, David, Moses–but also that this new kind of mythologizing forgets that greatness often comes at the expense of some great personal wounding in the past, present, or future (i.e. Jordan’s father issues, Armstrong’s marital strife, Urban Meyer’s breakdown). Total success is always a tenuous notion, and usually confutes either a hidden failure or a hidden wound. And much as we may love the stories of comeback kids and legacy programs and unbeatens, there honestly are none–and maybe, as Lane Wallace asserts, we’d be better off facing up to that, for their sake and ours.

The obvious fantasy personified by Pistorius is of the underdog overcoming overwhelming adversity to achieve triumph. A man without legs reaches the semi-finals of the 400-meter track event at the Olympics? “If that can happen,” one can just hear parents around the world telling their children, “then you can do anything.” Even if you’re not perfect. Or you have some physical defect. Or you’re sick.

It’s a powerful and uplifting message that we want to believe, in all its simplicity and potential for a happy ending. Fade to credits, everyone leaves inspired. Unfortunately, the equation of achievement is far more complex.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fxnqHvEbGnc&w=550]

…It’s an aspect to achievement that we often shove aside in our focus on the shining moments of record-breaking triumph. And that goes for more than just sporting feats and icons. A friend of mine, whose job gave him access to many of the top CEOs in America, told a similar tale about their motivations and demons. I’d kidded him, back in my single days, to keep me in mind if he knew an interesting CEO who was single and age-appropriate.

“I do,” he answered. “But the truth is, I wouldn’t wish any of them on you.”

“Why?” I asked.

“Because they’re generally not easy on their wives or families,” he answered. He went on to explain that he’d developed a theory about top-achieving CEOs. “Almost to a person, they’ve been denied something that really mattered to them, early in their lives. So they spend the rest of their lives making up for it. Achieving. And not only does that make them pretty focused on themselves, it also means that no achievement is ever enough. They’re driven.”

…That, mind you, is before you throw in the ego that develops with success or the impact that sudden wealth, power, and fame can have on people who are ill-prepared to cope with it. You spend years laser-focused on yourself and your own achievement. And then, if you’re successful, suddenly everyone else is focused on you, as well. As Thompson noted, “[Jordan] is used to being the most important person in every room he enters and, going a step further, in the lives of everyone he meets.” Those in Jordan’s life, Thompson says, are well versed in not only his achievements, but also “his ego, his moods, and his anger.”

Top-level achievement requires talent, to be sure. But it also requires tremendous focus and great sacrifice. It makes sense that many of the people willing to devote that kind of effort and make those sacrifices have some driving emotional or psychological need that makes the trade-offs worthwhile. For everything in life is most assuredly a trade-off. To be a Michael Jordan or a gold-medal Olympic athlete requires such single-minded focus that it also necessarily requires trading off a whole lot of balance in life and development—a weakness that can then be amplified with the rush of fame, money, and attention that success brings. Perhaps the surprising thing is that there are actually exceptions to the rule; top athletes, celebrities and CEOs who do manage to be balanced individuals, with balanced lives and an ability to focus on others instead of themselves.

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XJxj29vGTGU&w=550]

In view of all that, it’s not hard to believe that a kid who had both legs amputated at age one, who was six when his parents divorced and 15 when his mom died, would possess an excruciating drive to prove or overcome the insecurities or damage from those losses. Or that the same drive and traits that got him to the Olympics might be less suited for healthy interpersonal interactions. Or that the insecurities still lurked inside—demons that only got scarier with all the world’s focus on him as a perfect poster child.

So maybe we shouldn’t be so shocked. But we are. Because we don’t want to look at the complexity or costs of achievement. We want to paint our heroes pure, so we can indulge in our happy-fantasy hero-worship without having to feel queasy about it.

…Granted, Pistorius would appear to be an extreme case. To be clear: All charges against Pistorius are alleged, at the moment. And domestic violence, if that proves to be the cause of Steenkamp’s death, cuts across all segments of society, in the U.S. as well as abroad. High achievers do not have a corner on that market. The combination of insecurity, anger, and other damaged psychological traits that lead a person to abuse or turn violent toward women exists in all too many individuals and all too many places.

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XxNl69fLDs8&w=550]

But it’s worth pondering for a moment: For all of Michael Jordan’s ego and anger and moods, two sportscasters discussing the ESPN piece last week noted that Jordan wasn’t even in the top 50 of arrogant, egotistical sports figures they’d interviewed. That should give us pause, just as my friend’s comments about the motivators and costs of top achievement in the business world gave me pause. Why do we view people who achieve great personal success or achievements—especially those that involve an almost narcissistic focus on themselves—as romantic figures or role models?

We should, by all means, acknowledge great achievement. Because it does come at great cost. Nobody has it all. Nobody can have a level-10 career and excel in their personal life, as well. Not even men. They may looklike they have it all, but they don’t. Just ask their neglected wives and children. There are hard, firm trade-offs in where a person’s time and energy get directed, and every choice has a consequence. (And there’s much, much more that can and needs to be said on that subject.)

But when we look for role models, why do we gloss over all the demons, flaws, and costs, and build these singular high achievers into all-around “10s” in our images and minds? I’m not sure, but I suspect it’s because we want to believe the fairy tale. We want to believe that Prince Charming actually is a great guy, through and through. We want the simple, happy ending. And, perhaps we also want to believe that we, too, can focus on ourselves and achieve whatever we want without someone else bearing the cost that achievement requires.

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ekPyWzXMxc4&w=600]

COMMENTS

2 responses to “Michael Jordan, Oscar Pistorius, and the Year of the Heroic Fall”

Leave a Reply

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/20/books/review/missing-out-by-adam-phillips.html?_r=0

Great article Ethan. Steve Brown also says that when we idolize someone, it creates pressure which makes them more likely to fall. Brown said it in the context of placing pastors on a pedestal, but it has application here as well. Our idolatry of our heroes just exacerbates their woundedness by driving it further underground. Always enjoy your insightful articles.