This week we turn to Ernest Hemingway’s classic, beloved “Big Two-Hearted River”, a story about fishing in backcountry Michigan. Its stylistic technique is the best of any stories we’ve looked at (or probably will!) in this understated story about survival. Read along here.

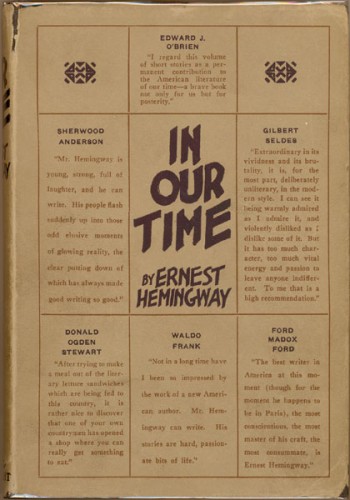

This story concludes Hemingway’s In Our Time, a beautiful collection of short stories that epitomize Hemingway’s ‘iceberg theory’, a method of storytelling that only gives the bare facts and leaves it up to the reader to make inferences. As Hemingway was himself a veteran of war, In Our Time has usually been interpreted as a book dealing with post-traumatic stress disorder in the wake of World War I, presenting wounded characters trying to cope with loss through alcohol, travel, or immersion in everyday minutia. The first time I studied this book – which contains almost no direct reference to the War – I remember the college professor telling the story of a Desert Storm veteran who had taken the class. He had sobbed during almost every story – it touched something deep within him.

This story concludes Hemingway’s In Our Time, a beautiful collection of short stories that epitomize Hemingway’s ‘iceberg theory’, a method of storytelling that only gives the bare facts and leaves it up to the reader to make inferences. As Hemingway was himself a veteran of war, In Our Time has usually been interpreted as a book dealing with post-traumatic stress disorder in the wake of World War I, presenting wounded characters trying to cope with loss through alcohol, travel, or immersion in everyday minutia. The first time I studied this book – which contains almost no direct reference to the War – I remember the college professor telling the story of a Desert Storm veteran who had taken the class. He had sobbed during almost every story – it touched something deep within him.

In context, this is a story about war, woundedness, and living with memories and ghosts. Hemingway’s prose is so short, direct, and concise because it speaks to a man focusing on the small details of life to avoid thinking about anything else. Almost all of the sentences employ parataxis, a style of writing sentences that focuses on bare facts and ignores their interrelationships, leaving gaps for the reader to decipher (for example, you almost never see the words ‘because’, ‘therefore’, ‘nevertheless’, ‘so that’, ‘in order to’ – it’s less inferential words like ‘and’ that join together details). His terse style forms a barrier to examining Nick’s character, his psychology, his dark past – but this examination is exactly what Hemingway is asking of his readers.

While “Big Two-Hearted River” is, in many ways, the consummate sportsman’s tale, Hemingway gives us more than enough clues to look beneath the surface to the emotional iceberg underneath. Nick’s obsession with controlling small details speaks to a deeply wounded man, and the detail that he had been desperately hungry before, but was unable to satisfy it, strongly hints that Nick is a war veteran himself (as do other stories featuring his character). In moving into the unpredictability, excitement, and spontaneity of fishing, Nick finds small emotional thrills. It provides him with excitement and purpose which help him reengage the emotional side of him repressed since the war, but he will be assaulted by the temptation to become obsessed with the thrill, sacrificing his stability.

While the other stories we’ve looked at examined a character heading into a place of disruption (death of youthful naivete, murder by an escaped convict, running into Jesus in the gunner’s bay of a B-29), Nick is coming from a place of disruption and woundedness. His friend Hopkins was killed in the War after being drafted, Nick has gone hungry himself, and his sexuality is compromised (“other needs”, 981; obsession with outdoorsy masculinity, Hopkins as the only meaningful relationship mentioned). Taking what we can from Hemingway’s sparse characterization, Nick feels a deeply-rooted, suppressed guilt. He tries to convince himself that he does indeed deserve another meal when he tells himself, “’I’ve got a right to eat this kind of stuff if I’m willing to carry it.’” But his voice sounds “strange in the darkening woods. He did not speak again.”

This is a man marked by guilt (survivor’s guilt is a great candidate, but it’s impossible to say for sure), feeling like he even has to earn his next meal through hard work, a self-atonement of sorts. But his consolation rings hollow and empty; his voice is detached from himself, and he cannot believe it, no matter how much he wants to. Fleeing from the “need for thinking, the need for writing, other needs”, he tries to reconcile all of these splits and psychological dissonance by immersing himself in the everyday, physical world in which he does know how to control things, predict things, and most of all, has the skills needed to survive.

In Nick’s case, his extreme meticulousness is a reaction to a repressed feeling of powerlessness (in most of his other stories and novels, Hemingway is obsessed with male impotence and woundedness. He took a mortar between the legs during WWI himself). Nowhere is this clearer than a paragraph that’s unbelievably matter-of-fact and journalistic, on page 983 of the version hyperlinked above. Nick is creating his world for the night in building the tent, and everything must be perfect, no detail spared in Nick’s preparation or in Hemingway’s brilliant account of it:

Nick was happy as he crawled inside the tent. He had not been unhappy all day. This was different though. Now things were done. There had been this to do. Now it was done. It had been a hard trip. He was very tired. That was done. He had made his camp. He was settled. Nothing could touch him. It was a good place to camp. He was there, in the good place. He was in his home where he had made it. Now he was hungry.

Hemingway’s mastery of indirect detail is apparent in the ambiguity of exactly how “this was different.” Is he even happier because things are done, or is he becoming unhappy from purposelessness? He’s safe, but hunger creeps in. As he moves from work time (hiking, navigating, etc) into idle alone-time, the sentences become more and more constricted as Nick tries to so he wards off introspection, the great terror of a veteran who doesn’t want to deal with the horror he’s seen. But even in prioritizing simple thoughts and focusing on how settled and safe he is, Nick’s hunger impinges.

Psychologically, there are two ways to take this last detail. First, it could be symbolic of the fact that his needs as a wounded person can never be met, because his inner unsettledness and dissonance bubble up to the surface no matter how hard he tries to convince himself he’s in “the good place.” Second, the hunger provides Nick with purpose in preparing his meal. Having all his duties accomplished may be too much for him – it’s hinted that he’s unhappy for the first time all day – and hunger presents him with another task to keep him busy, to keep his mind off things, to earn his keep. It’s especially significant to note that Nick only encounters his guilt once all of his tasks for the day have been accomplished (as he’s eating), he encounters it immediately, and he responds by throwing himself into another task.

There were two possible interpretations of Nick’s hunger, but we can combine them. He tries to stifle his inner powerlessness and guilt by controlling his own little world, building “the good place.” Yet this desire for control as a response to powerlessness can never be filled, so his desire is unquenchable – he will always need more tasks to retain feelings of control. Unhappiness from an unquenchable desire for self-justification as a response to guilt…sounding familiar? But as understated as Hemingway is, perhaps at this point we really are overinterpreting…

There were two possible interpretations of Nick’s hunger, but we can combine them. He tries to stifle his inner powerlessness and guilt by controlling his own little world, building “the good place.” Yet this desire for control as a response to powerlessness can never be filled, so his desire is unquenchable – he will always need more tasks to retain feelings of control. Unhappiness from an unquenchable desire for self-justification as a response to guilt…sounding familiar? But as understated as Hemingway is, perhaps at this point we really are overinterpreting…

Either way, Hemingway has so far given us a touching, tragic picture of a man attempting to deal with his emotional wounds and, in perfect Hemingway style, has done so without talking directly about Nick’s past, his emotions, or ‘coping’, though this last idea is the central theme of the story. He’s done all of the characterization work by over-including small details, making vague, minute references, and manipulating his sentence structure to create an emotional effect. And his style matches his subject matter perfectly: Nick is not one to engage directly with his emotions, so Hemingway denies his readers that possibility, too. So we know about Nick, his past, and his current struggles – the stage is set. And thus ends Part 1 of the story.

* * *

Given what we’ve seen so far, it’s remarkable that this story ends on an upbeat – even happy – note. The Christian organization YoungLife often gives a talk about human sinfulness and the cross and then, after reflection time and a night’s sleep, gives a talk about resurrection and new life. Hemingway’s doing much the same here in his division between Part 1 and Part 2. His central themes of learning how to live in a fallen world as a wounded person and the oft-cited ‘grace under pressure’ come into the fore in Part 2.

Nick has found a purpose in fishing – a telos, if you will – and so he eats his breakfast hurriedly. In Part 2, the mundane details of his life are no longer ends in themselves, but means to a purpose which actually excites Nick, whereas the details only staved off unhappiness (recall EH’s description that “he had not been unhappy all day”, not that he had been positively happy). His happiness is moving from the undisturbed happiness of negating his problems into the positive happiness of having a purpose. Hemingway himself was a severely depressed sportsman, so he may be empathizing with Nick and writing part of himself into the story.

Now that the details are being subordinated to a purpose (catching fish), Hemingway’s prose begins to open up just slightly. In the story’s second half, he’ll occasionally break out of his short, terse parataxis and into a freer-flowing hypotaxis, in which his clauses begin to interrelate with words like ‘while’, ‘because’, ‘so.’ He has a purpose and structure, so the little details are subordinated, syntactically, to catching a fish. It’s another subtle way that Hemingway’s frustratingly sparse style sets the story’s and character’s moods for him.

Now that the details are being subordinated to a purpose (catching fish), Hemingway’s prose begins to open up just slightly. In the story’s second half, he’ll occasionally break out of his short, terse parataxis and into a freer-flowing hypotaxis, in which his clauses begin to interrelate with words like ‘while’, ‘because’, ‘so.’ He has a purpose and structure, so the little details are subordinated, syntactically, to catching a fish. It’s another subtle way that Hemingway’s frustratingly sparse style sets the story’s and character’s moods for him.

Now we come to the story’s enveloping action, which is the conflict between Nick’s need for stability and his desire for emotional fulfillment. He thinks to himself that he won’t try to flop the pancake, but then he flops it anyway. In order to do the simple things he wants to do, Nick must take risks. He’s tempted to test his pancake-flopping skills in order to cook a better pancake, but the act of dong so risks unraveling a thread – albeit a tiny one – of the world he’s built out here in the woods. Normally, this detail would be insignificant; again, however, it’s one of the very few direct insights into Nick’s thoughts we’re granted, so Hemingway is taking great care over the detail. Indeed, it foreshadows the final conflict of the story, which is Nick’s choice between fishing the swamp or staying upstream:

He was certain he could catch small trout in the shallows, but he did not want them. There would be no big trout in the shallows this time of day.

Now the water deepened up his thighs sharply and coldly. Ahead was the smooth dammed-back flood of water above the logs. The water was smooth and dark; on the left, the lower edge of the meadow; on the right the swamp.

Nick’s performing a balancing act between the safe meadow with poor fishing and the tangled swamp with its promise of the largest fish – it’s a classic Hemingway image of the compromised male character successfully navigating between the danger of sparse unfulfillment and the danger of losing oneself in the morass of desire. He risks doing the latter after losing a huge trout:

Nick’s hand was shaky. He reeled in slowly. The thrill had been too much. He felt, vaguely, a little sick, as though it would be better to sit down….

He went over and sat on the logs. He did not want to rush his sensations any.

He wriggled his toes in the water, in his shoes, and got out a cigarette from his breast pocket.

The excitement of fishing is giving him the same sort of purpose he felt during the War (or at least at some point in his previous life), but the excitement is a threat to coping, to stability. Nick knows himself well enough to know that he can only take in a limited amount of excitement, of sensation, at a time. Besides evoking images of excitement and simultaneously mental duress, the image of a shaking hand lighting a cigarette also evokes a man trying to gain some emotional detachment from the excitement. The cigarette, in a very limited way, provides this distance and restores a small sense of stability, of control, of self. Even though Nick temporarily lost his control (“too fast”) and even lost the trout, he still (barely) manages to continue navigating the tension. He will deal with excitement; he will return to the emotional world, but not too quickly for him to process. He very nearly does it too quickly, but a break from the river equilibrates him.

The story’s central symbol, of course, is the river. Nick can tell his position from the river; the river allows him to engage his emotions for the first time all trip; the river exerts pressure upon him and is dangerous. The river here is a symbol for Nick’s own emotional life, the two-heartedness he feels in the need for mundane stability (the shallows) and the need for emotional excitement (the deeper, faster water). As Nick tries to reel in the large trout, Hemingway notes that he’s leaning backward into the river, and it’s mounting against his thighs. He’s bracing himself against the river’s pressure, but his emotions are mounting, and they almost overwhelm him. At the same time the nicotine is giving him some emotional distance from the fight with the trout, he’s stepped out of the river, too. The emotional avoidance is far from ideal, but Nick is wise about knowing himself and processing only as much as he is capable of handling at a given time. Temptation tells him to immerse himself in the river and process everything at once; the voice of grace gives him room to take it in as he must – it gives him time, space, and permission to engage his emotional life gradually, without too much excitement all at once. The voice of grace frees him to listen to the voice of simple prudence.

Nick’s conflict builds as he seeks more excitement, starting out back in the shallows, working gradually into the “deepening” water, avoiding spots with snares or potential tangles. Finally he contemplates fishing in the swamp, which provides incredible fishing at the cost of exhaustion:

He felt a reaction against deep wading with the water deepening up under his armpits, to hook big trout in places impossible to land them. In the swamp the banks were bare, the big cedars came together overhead, the sun did not come through, except in patches; in the fast deep water, in the half light, the fishing would be tragic. In the swamp fishing was a tragic adventure. Nick did not want it. He didn’t want to go up the stream any further today.

… There were plenty of days coming when he could fish the swamp.

The story ends with the grace of time, days ahead when Nick will be in a better state, after he does more and more fishing and gradually learns how to control the excitement, how to re-enter thrill without the perils of obsession, of being mired in a “tragic adventure.” Again, Hemingway’s craft is brilliant: he’s kept the tone so even that the word “tragic” leaps off the page, arresting the reader instantly and letting her know that “tragic adventure” has been the story’s exact subject the entire time. As an emotionally wounded man – as are we all – Nick is incapable of entering this tragedy in a healthy way, and even the limited parts of the emotional, lively river that he’s experienced this particular day have almost been too much. But living there, as much as one can, is certainly better than living in the artificial world of control and meticulous detail, of terse repression.

Grace says that there are other days to enter the deepest parts of the river, of the tragedy that is our own fallenness. There are other days to engage it, and we don’t have to do anything right now, because our capacity to handle life’s deepest emotional truths is a work in progress. We are all recovering something-or-anothers, and there’s an indefinite amount of time for full recovery to happen. This, at least, is Hemingway’s take on “grace under pressure”, or “coping”, or living one’s life in a way that’s both honest and practical.

NB: If this had been an O’Connor story, Nick probably would’ve unintentionally hooked a huge trout in the shallows, been dragged into the swamp as he desperately held onto the rod, drowned in the swamp, been CPRed by old man, and set off down the road, devastated and liberated. In all seriousness, EH’s and FOC’s ideas of how change occurs seem, on the surface, extremely divergent. My best attempt at explaining the discrepancy would be that Flannery focuses on the Spirit’s action despite human interference while EH focuses more on the little human action we’re capable of. My second best guess would be that most of Flannery’s characters are prideful and need a disruption or downfall; Nick is coming out of his place of woundedness and needs to process his emotional damage while also maintaining distance from the horror of his memories.

Check back next week for pre-modern French master Gustave Flaubert’s views on sanctification in a charming, mildly horrific retelling of “The Legend of St. Julian the Hospitalier.”

COMMENTS

9 responses to “Short Story Wednesdays: “Big Two-Hearted River” by Hemingway”

Leave a Reply

I’ve read and re-read this story for 30 years. this is the best appraisal of it I’ve ever seen. Thanks, Will.

Re-reading is one of the joys of short fiction. My thanks also go out to WB. I hope that some Raymond Carver works its way into this series.

This story has been following me around all day. There are times when I use fiction to engage my problems. There are times when I use fiction to distract myself (to quote Bob Dylan, “I need something strong to distract my mind…”) The latter was usually accompanied by some guilt afterwards. Perhaps Hemingway, or WB, is giving me permission to use fiction as a distraction since there will be a time to engage, confront, “fish the swamp.” This is in contrast to another story I re-read last night, Eveline by James Joyce, where the characters unwillingness to run away keeps her trapped. I guess “running away” isn’t always a bad thing.

Thanks for this thoughtful essay on “Big Two-Hearted River”. It is also, for me, among, if not the most, re-read of all the short stories I’ve ever encountered. I always took from the description of the burned-over country Nick traverses that he is returned from war, and that his journey is a kind of convalescence. I could as well imagine Nick thinking, “It could not all be burned. He knew

that” with him hunkered down in a trench in No-Man’s Land. And Hopkins is gone, and Bill is not with Nick on this trip, and the way EH describes that long ago fishing trip on the Black River, the party included more than just Hopkins, Bill and Nick, yet Nick returns to the two-hearted river alone. There is this sense of loss and change and a mournful hearkening back.

I respectfully question your description of “Nick’s obsession with controlling small details” though, since what EH is describing is not that sort of obsession that is often characteristic of depression, but of the devoted physical practice that underlies the zen-like appeal of fishing, particularly with a fly-rod and reel set-up. So too, in the set-up of the camp, does EH convey the simple pleasure and satisfaction of carving comfort out of the inconveniences of sleeping out under the stars. I don’t disagree with your premise, of Nick coming from and recovering from a woundedness, but I see in Nick’s immersion in his tasks and surroundings, not escapism or some attempt at control for its own sake, but a kind of physical meditation merging, if not crossing over into the spiritual. When Nick says to himself, as he sits stream-side, that “He did not want to rush his sensations any” it wasn’t in fear that he might be overwhelmed. It was, instead, his desire to be fully alive and appreciative in that moment, to luxuriate in the experience, good and bad. My sounding of the Iceberg there, is that the place he had been coming from (and wounded in) afforded no such opportunity, either in terms of time or being anything but unrelenting, burned-over horror.

These feelings Nick has — the excitement of the strike and the set of the hook, the crest-fall of a broken leader — are precisely my experience of fishing, without, thankfully, my ever having experienced the horrors of war. So also, are Nick’s mixed feelings about fishing the swamp. On nights I fret awake, I often soothe myself to sleep by recalling some fishing I’d done, or imagining some trip in the future, and I always take a kind of lucid-dreaming care to avoid those darker, more dangerous fishing grounds, like the swamp, where trees have fallen into the lake. It is not fear, exactly, that steers me clear, and there certainly lies the possibility of some great catch. But there is a serenity in the well lighted cleaner fishing grounds, even if there are fewer lunkers lurking there.

I don’t think of Nick’s journey as a retreat from reality into a small and artificial (in the sense of being subject to human control) fantasy, but as a return to an enduring and timeless reality. And his re-finding his place in it and his healing.

“Now as he watched the black hopper that was nibbling at the wool of his sock with its fourway lip, he realised that they had all turned black from living in the burned over land. He realised that the fire must have come the year before but the grasshoppers were all black now. He wondered how long they would stay that way.” A little while further on, Nick makes camp and in the morning catches some cold-stunned hoppers for bait, and they are not black.

Thanks so much, Esoth! Beautiful thoughts on the story, especially the lucid-dreaming part. For me, Hemingway’s style conveys the obsession with control, so stilted and meticulous and, in a sense, blocked. Parataxis can be used to emphasize stiltedness or repression, but of course, it earned its place in modern lit by leaving space for the reader’s interpretation. As a non-fly-fisherman, I didn’t get the same sense of serenity that you did, but the minimal style certainly allows for both interpretations, and you’re tracking with the psychological elements of fishing more closely than I can. All that said, I don’t think the two are entirely exclusive – part of the appeal of camping is a control thing, but maybe this control gives space for serenity…OCD tempered by peace and calm, or vice versa.

Thanks for the thoughtful analysis of this story. I can never get enough of Hemingway. Started reading him when stationed in Northern Italy. I was never a lit major, so I enjoy these commentaries. Recently read “The Old Man and the Sea” with my son. He loved the story. He is only 10. Makes me think I have done something right as a dad, that my son likes Hemingway. I was struck by the Christological implications of that story. Just a great writer.

Unsure if this site is still active, but I’d like to get the book this short story is in: at home and abroad: american fiction between the wars. But I can’t seem to find it. Could you give me the ISBN or at least who edited it? My search for it on Goodreads and Amazon yield a Harold Bloom with the subtitle, but I can’t see “inside” the book to the ToC so unsure it is the right one.

Thanks in advance for your help and for this article about the short story.

Wow, what an intelligent discussion. It taps into my deepest longing to share my love of great writing with others. Thanks to the creator of mbird.com and his/her followers.