[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QMy3AbpkYvw&feature=results_video&playnext=1&list=PL9426066D963C7A16&w=550]

Flow, river, flow

Let your waters wash down

Take me from this road

To some other town

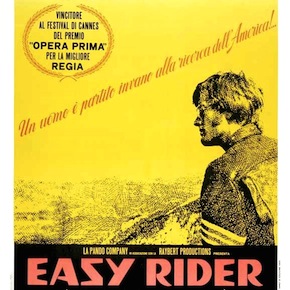

It is a disservice to lump Easy Rider into the slews of “counterculture” or “indie” filmscapes of the late 1960s and early 70s. It’s not that these descriptors aren’t accurate–both are quite true–or that it wasn’t a hippie-handed film, standing against those “scissor-happy, beautify America” typesetters that George Hanson (Jack Nicholson) could still so aptly classify. What makes it different, though, and thus limited by such descriptors, is that it so inclusively sups with the whole (“All walks of life!”) far too much to stand against it. As Peter Fonda said in his interview for the Shaking the Cage documentary, the indictment was aimed at nothing less than the whole of America: “We don’t let anyone out of the theater…you can’t put it under the seat in the theater–you have to truck it home with you.”

From the beginning Fonda and Hopper (producer and director, respectively) sought to create a true-to-life American Road Odyssey, a spur-studded tribute to freedom–the engined outlaw–the “Machine Western” as Fonda described it at Cannes. You see it in the names of Fonda and Hopper’s characters, Wyatt and Billy. You see it in the fringed leather, the fireside chats, the independence. It is a modern rendering of two paper-cut, Captain America & Bucky cowboys, and yet, the rendering pushes the tradition of American freedom to its outer reaches. Hopper described the term ‘easy rider,’ as a man who lives off of a whore, not as her pimp, but as her dependent lover and ‘easy rider.’ Suddenly a movie about freedom is drastically discolored; freedom, everything is suddenly not what it seems.

Take the flag. The flag decaled on a teardrop gas tank on a California chopper, on a helmet, on the back of a black leather jumpsuit, multiplied almost in the hope that its reincarnations compound the freedom. And yet the very symbol of freedom is immediately a showy one, a heroic impracticality. The chopper was all about style and yet had painful consequences for a cross-country journey, as Fonda would even later say after his days of shooting on the bike. And there’s the tube of drug money, shoved secretively in the flagged tank, an ominous image of greed beneath the stars and bars.

Take the commune. The confounding hippie retreat, where lovers commingle and babies run naked and disregarded, comers and goers as spiritual messengers, abundant drug use. A valiant effort, but a dire one–an image sticks of serious-faced young men and women sowing seed on hard, dry dirt. It doesn’t seem ridiculous but it seems fallow.

Take the jail scene, or any of the scenes following for that matter, and you see an ill-conceived fellowship of “free men” whose interaction with the world around it stirs a defensive reaction. Hopper and Fonda are imprisoned for joining a parade, a celebration. Hopper and Fonda sleep outside because rooms suddenly become occupied at motels upon their arrival. Nicholson as the ACLU lawyer (lawyers of liberty!) George Hanson, someone who would be lumped with the respectable elite, joins the chopper voyage and, despite his comely appearance, becomes lumped in as one of the freaks at the Louisiana diner. No one likes to see the “freaks” of freedom, but what’s worse is one of “us” becoming one of “them”. George, before his murder, delivers the pivotal monologue (the monologue that started Jack Nicholson’s career) on the paradoxical reality of freedom-hunger.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zHd6m_cirrU&w=550]

Kierkegaard talked about anxiety as a “quivering at the edge of freedom,” that freedom understood rightly is a horrifying edge to stand on. And it is this kind of perspective that makes such violence understandable.

Upon first seeing the film, I was left at the end of the scene thinking that George Hanson was giving the last rites of the hippie age of freedom, a glorifying salute to the kind of life it meant in the commune. That maybe Hanson was pointing them back to the yurt. I took it to mean that Hanson saw this age of peace and love as the arrival of perfect freedom. That that life would be looked down upon, even hated, but that it was the image, the realized telos of life. And maybe it was the last rites. But that translation complicated the buildup to the final scene. The chopper duo finally land on the other side of New Orleans, after a weekend of prostitutes, acid, and graveyards (where Wyatt weeps in the arms of a Lady Liberty likeness, screaming “I hate you mother! Why did you leave me?”), and the completion of their journey feels like a deflation rather than a culmination. Camping out, Billy is glad to have arrived at freedom’s gate, money safely secure in the teardrop-tank. He tells Wyatt, “You go for the big money and you’re free, you dig?” For Billy, freedom is bound to acquisition, freedom is self-sustained self-license, freedom is take-the-money-and-run, it is retiring in Florida. It is here when Wyatt speaks up: “We blew it.” Notice the American flag laying down to die. Even this freedom is bound up.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qsvUz9DsElA&w=550]

After the bikes blow up, after the ride is over, the heli-camera pans out over the wreckage, delineating the road that led them there, and a heavy, rolling river to its side. Fonda insinuates an answer for freedom in an interview about that final scene, where he tells Bob Dylan what a ballad for the Easy Rider might be: “You see, there’s the road that man builds, and we can see that, and there’s the river, and that’s the road that God builds, and so you can what happens on the road that man builds.” Hence the Ballad.

The river flows

It flows to the sea

Wherever that river goes

That’s where I want to be

The movie makes known that no man is truly free, but bound up in himself, in his conceivings. Freedom then, by the likes of Dylan and the Byrds, the final sounds of the film, has to do with being led. Not leading, not taking, not running. It is a surrender undo the road of God, a baptism into the river, a falling in and letting go.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply