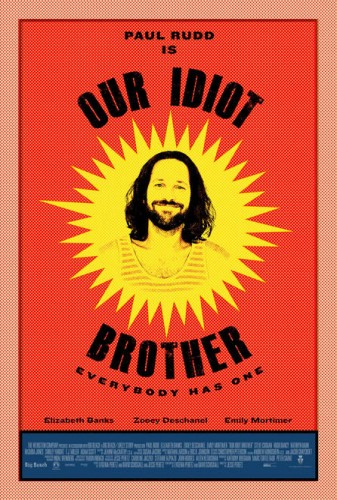

Who can deny Paul Rudd? Even The A/V Club’s unfavorable take on the new film Our Idiot Brother, recently out on DVD, is less a knock on the film itself as it is a disappointment that no one really could keep up with Rudd and his charisma:

Who can deny Paul Rudd? Even The A/V Club’s unfavorable take on the new film Our Idiot Brother, recently out on DVD, is less a knock on the film itself as it is a disappointment that no one really could keep up with Rudd and his charisma:

“Rudd ably carries the film while retaining a light touch, though even with Rudd in the lead, it’s still a featherweight trifle, an afternoon nap of a feel-good comedy… Rudd might just be cinema’s first Manic Pixie Dream Boy: the dynamic is the same—impish life-lover devoid of an inner life or personal needs shakes up the lives of the depressed and anxious—even if the gender dynamics are reversed.”

Though The A/V Club didn’t make a note of it, most reviews did mentioned that Peretz intended Ned to be a modern-day version of Dostoevsky’s Prince Myshkin in The Idiot, the Christic response to the anguished central figure Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment.

In The Idiot, Myshkin returns to St. Petersburg from several years in a Swiss sanitarium to the world of Russian status and social exchange, immediately finding himself both the center of exclusionary gossip, and also the beholder of intimate trust. Myshkin is the embodiment of foolish love: he has no social graces, no stratagems for life fulfillment, no hiddenness, no games. These innocent qualities are used against him for society’s profit while simultaneously serving as the reason almost everyone around him never wants him to leave. He’s the archetypal Type-B: there is no routine or plan to his life. Instead, he is willingly surrendered to the needs of the day, whatever they may be. His surrender produces unseen vulnerability in the inner-lives of the characters around him (think Theophilus North), while ensnaring him in a “loserdom” that forever leaves Myshkin in the role of, not the player, but the played.

Loserdom in Our Idiot Brother takes a similar if slightly more palatable shape. This means that, at points, Dostoevsky’s potent social innuendos are exchanged for awkward hipster humor, with Myshkin’s religious acuity translated into Ned’s dewy-eyed hippy-therapist.

Loserdom in Our Idiot Brother takes a similar if slightly more palatable shape. This means that, at points, Dostoevsky’s potent social innuendos are exchanged for awkward hipster humor, with Myshkin’s religious acuity translated into Ned’s dewy-eyed hippy-therapist.

Though it plays out differently, there’s a thematic consistency to both characters. Both the film and the novel are depictions of Christ-like surrender, and the effect is has on people exposed to it. In both texts, this surrender is foreign; the openhandedness which defines Ned comes across to those around him as helplessness, a lack of fortitude, or mooching slobbery. He cannot seem to get it together, every moment of hope is a soon-to-be misfire—and yet the film provides the backstories for each of Ned’s hapless missteps, all of them compassionate moments of passivity that lead him into the pit. In the opening scene at a farmer’s market, Ned benevolently hands over a bag of weed to a cop who’s convincingly demonstrated his “tough week.” There’s no shrewdness from Ned, only a willingness to help, and it quickly results in his imprisonment. He’s arrested for his compassion. This is a treehugger in whom there truly is no guile.

It is worth noting, at the film’s beginning, the particular environment in which this first occasion of surrender takes place. Set against a scene of ‘fruitfulness’—that is, the local farmer’s market fruit stand—we are confronted with a very familiar storyline, one reminiscent of Genesis’ Eden. Here, the central figure is duped, in an urban garden of sorts, by a perverted authority figure, nearly serpentine in nature. Though wearing a policeman’s uniform, his trustworthiness as an agent of justice is soon doubted after his casual admission about marijuana cravings and unapologetic requests for the substance. The once-friendly “for-the-people” policeman becomes an agent of distortion and distrust. His agenda is to take advantage of Ned’s kindness, penalize him for his empathy, and lock the poor guy up. Locked up he is, and for the remainder of the film, Ned, like Myshkin, is indeed played time and time again by both his circumstances and his peers.

Or is there?

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jjq_GjjMWmM&w=600]

Any pro-active, self-controlled ‘captain of their own ship’ would be quick to blame Ned for his plight. A human being so out of control of his or her own life, void of entitlements, rights, demands, and possessions is disengaged to the point of their own demise. Well, leave it to Ned, whose good nature turns this very judgement on its head, bearing equal doses of lightheartedness and truth: it is not Ned who’s in trouble—it’s every one else around him. Perhaps this is why ‘no one could keep up with Rudd and his charisma.’ Writing off Rudd’s foolish, passive lifestyle as mild stoner-humor and/or key elements of a feel-good comedy would be a mistake. His affable surrender is the very thing we are meant to engage, as destructive as it may seem to the film’s plot (and our own lives!). By limiting his character to nothing more than granola love and cheap laughs, we find ourselves in the company of Ned’s sisters in the film, who can only see Ned as their messy, sometimes endearing, but always inconvenient sibling. Instead, we would do well to focus less on Ned’s relative lack of personal achievement, and more on the raw, honest reality and truthfulness that follows him wherever he goes, burning bridges all the way to film’s end. His perfect love for others–despite his imperfect humanity and lack of personal agenda–is the crux of it all, the place where Ned’s quirky compassion collides with the self-driven, close-handed lives of those he encounters.

What, then, is this film saying? It seems that, left here, the message would be a cautionary tale of almost Rand-like proportions: take what you can get, don’t surrender (at least not anything real), leave no openings for an attack. The complicating element, though, is that every other character in the film represents (in some way) this kind of guiding philosophy of protectionism… And one by one, their fearful self-centeredness leads them into crisis aversion and loveless marriages and general apathy. Ned’s own sisters take advantage of his honesty for their own uses and yet bastardize him when his honesty turns the coin on them. “Our idiot brother just ruined my freaking life!,” screams Deschanel, the youngest of the sisters. The protectionist way of life, then, is a schizophrenic one that loves Ned’s goodness when it serves them, but hates it when it’s used against them, e.g. his inability to lie. The film in no way supports the protected life—it asks, “Who are the real idiots here?”

And the truth is, as much as the characters in the film don’t want to be with Ned, they also don’t want to be without Ned. His sweet, jovial personality is undeniably attractive, if also confusing to those whose hidden ambitions nearly always turn out void once exposed to the Ned-effect (despite their unrelenting efforts to conceal them). He quickly becomes the awkwardly lovable agent of crisis—within weeks of living amongst his sisters, a divorce has been instigated, infidelity has been exposed, jobs have been lost. Everything seems to go wrong when goodness rears its bedraggled head—who wants this kind of upheaval (and pain) invading their homes? By the end of film, though, it becomes evident that this is precisely the kind of upheaval and pain that has already invaded the home, and that Ned, in love, has only brought it from its dark recesses.

The Christological parallels are not one-t0-one of course. For one, Ned has a tendency to over-apologize, always second-guessing what he says and how much he says, and has a fairly saccharine anthropology; he says at one point that “if you give people the benefit of the doubt, seeing their best intentions, they will rise to the occasion.” Um… Regardless, the thrust of the picture is the redemptive power of surrender—a life that gives up, that takes the rap, that isn’t thinking of itself 24/7, that turns the tables on personal control precisely because those things genuinely don’t matter to it. This is the kind of surrender that breeds new life and hope in those that encounter its reckless embrace. In other words, Ned, like Jesus, is a healer.

[youtube=www.youtube.com/watch?v=8F6ADjZgRCs&w=600]

COMMENTS

3 responses to “Mockingbird at the Movies: The Holy Foolishness of Our Idiot Brother”

Leave a Reply

Very nice review. I’ve been interested in seeing this film ever since I heard The Idiot was an inspiration. By the way, I had never considered Myshkin as Dostoevsky’s counterpoint to Raskolnikov. I can see that. Thanks for the insight.

This was very interesting. Thank you.