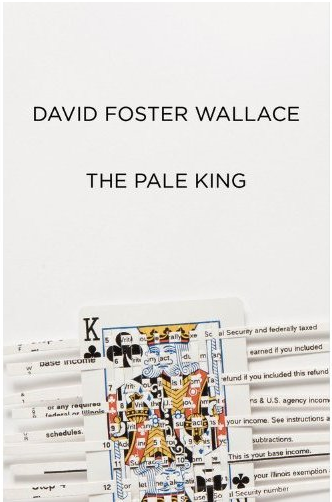

Tax Day marks the release of Mockingbird icon David Foster Wallace’s posthumous novel, The Pale King. Quotes forthcoming, but from the few reviews that have appeared already, it sounds predictably ripe… Italics mine.

Michiko Kakutani in The NY Times: [DFW’s] posthumous unfinished novel, “The Pale King” — which is set largely in an I.R.S. office in the Midwest — depicts an America so plagued by tedium, monotony and meaningless bureaucratic rules and regulations that its citizens are in danger of dying of boredom.

Just as this lumpy but often stirring new novel emerges as a kind of bookend to “Infinite Jest,” so it demonstrates that being amused to death and bored to death are, in Wallace’s view, flip sides of the same coin. Perhaps, he writes, “dullness is associated with psychic pain because something that’s dull or opaque fails to provide enough stimulation to distract people from some other, deeper type of pain that is always there,” namely the existential knowledge “that we are tiny and at the mercy of large forces and that time is always passing and that every day we’ve lost one more day that will never come back.”

Happiness, Wallace suggests in a Kierkegaardian note at the end of this deeply sad, deeply philosophical book, is the ability to pay attention, to live in the present moment, to find “second-by-second joy + gratitude at the gift of being alive.”

—————

Garth Risk Hallberg in NY Magazine: The Pale King is, for great swaths, an astonishment, unfinished not in the way of splintery furniture but in the way of Kafka’s Castle or the Cathedral of St. John the Divine. And it reduces chatter about the provenance of its author’s late renown to background noise. The book demands our attention precisely because while we’re reading it, David Foster Wallace is again the most alive prose writer of our time—and the one who speaks most directly to our condition.

The Pale King treats its central subject—boredom itself—not as a texture (as in Fernando Pessoa), or a symptom (as in Thomas Mann), or an attitude (as in Bret Easton Ellis), but as the leading edge of truths we’re desperate to avoid. It is the mirror beneath entertainment’s smiley mask, and The Pale King aims to do for it what Moby-Dick did for the whale.

Empirically, the self is “a kind of box … or prison,” and in our compulsion to escape—via drugs or TV or idol worship—we box ourselves in emotionally, spiritually, rhetorically, and civically, as well. What’s new in The Pale King is that Wallace thinks he’s onto a solution. “The entire ball game,” one character decides, “was what you gave your attention to vs. willed yourself to not.” Boredom, in this analysis, is nothing more or less than the urge to wiggle away when there’s nothing left to entertain us. And if we could somehow ride it out, attend to our inattention, we might find ourselves in the presence of what connects us: longings, loneliness, mortality, and maybe even, one of Wallace’s notes says, “gratitude at the gift of being alive.”

In the end, Wallace’s body of work amounts to an extended philosophical experiment. Can “morally passionate, passionately moral” fiction help free us from the prisons we make? To judge solely by his suicide, the experiment would seem to have failed. Then again, watching him loosed one last time upon the fields of language, we’re apt to feel the way he felt at the end of his celebrated essay on Federer at Wimbledon: called to attention, called out of ourselves. Jesus, just look at him out there.

—————-

John Jeremiah Sullivan in GQ [Believe it or not, if you only have time to read one, read this one]: “The whole question of whether we can call this “a Wallace novel” becomes unsolvable. If we want another ending, we could say this: The Pale King, as we have it, is true to Wallace in a very important respect. He himself was unfinished, unresolved. There’s a great Stevie Smith poem called “Was He Married?” It’s her argument that normal human beings are more heroic than gods. Their difficulties are much greater, she says, “because they are so mixed.” Wallace was so mixed. He was ambivalent and conflicted, about, among other things, the difference between the kinds of writing in this novel. He wasn’t sure which he preferred, or how they might go together. And what if the one he wound up valuing most wasn’t the one he was best at, by nature?

It’s this quality, of being inwardly divided, that risks getting flattened and written out of Wallace’s story by his postmortem idolization, which would make of him a dispenser of wisdom. We should guard against that. We’ll lose the most essential Wallace, the one that is forever wincing, reconsidering, wishing he hadn’t said whatever he just said. Those were moments when his voice was most authentically of our time, and they are the reason people will one day be able to read him and feel what it was like to be alive now.

Wallace’s work will be seen as a huge failure, not in the pejorative sense, but in the special sense Faulkner used when he said about American novelists, “I rate us on the basis of our splendid failure to do the impossible.” Wallace failed beautifully. There is no mystery whatsoever about why he found this novel so hard to finish. The glimpse we get of what he wanted it to be—a vast model of something bland and crushing, inside of which a constellation of individual souls would shine in their luminosity, and the connections holding all of us together in this world would light up, too, like filaments—this was to be a novel on the highest order of accomplishment, and we see that the writer at his strongest would have been strong enough. He wasn’t always that strong.

COMMENTS

2 responses to “Paying Taxes To The Pale King”

Leave a Reply

Dude. Take some time off 😉