Last week we posted part 1 of Mockingbird’s exclusive interview with Mark Galli, Senior Managing Editor of Christianity Today. Galli’s experience—from local pastor, to magazine editor, to columnist, to author—has all reflected and informed his passion for a cross-centered, true-to-life articulation of the Gospel. Part 2 of the interview explores Galli’s view on transformation in the Christian life, the place of spiritual disciplines, and the future of Evangelicalism. Enjoy!

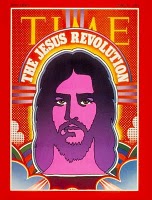

Mockingbird: Earlier you pointed out the tendency among Evangelicals towards activism, an “addiction to the horizontal.” As someone who’s been in the Evangelical world for a long time, do you see connections between the current activism (for example, in the Emergent Church movement) and earlier similar movements (like the Jesus people in the 1960s and 1970s)?

Mockingbird: Earlier you pointed out the tendency among Evangelicals towards activism, an “addiction to the horizontal.” As someone who’s been in the Evangelical world for a long time, do you see connections between the current activism (for example, in the Emergent Church movement) and earlier similar movements (like the Jesus people in the 1960s and 1970s)?

Well, certainly emergent folks like to think of themselves as breaking away from Evangelicalism, but there’s so much about their movement that’s just a new chapter of an old book. And actually, not even a new chapter, but a repeat of a lot of evangelical characterizations.

For example, first of all there’s the rejection of the establishment (which in their case is Evangelicalism) and second there’s this notion that somehow they can create a fresh a way of doing church that is somehow more biblical or authentic (which is another Evangelical assumption about the world), and third, that they’re very activist, that they’re going to go out and change the world. Now in this case, they’re not interested in evangelism as much as they’re interested social justice. But it’s very much about getting their hands dirty in the world, and doing something for Jesus. So in that regard, the emergent movement is very Evangelical. And of course, they’d be shocked and appalled to hear that, but that’s my take on their movement.

Unfortunately, the leaders of the emergent movement have pushed that envelope so far that I really can’t tell much difference between what they’re doing and nineteenth century liberalism, which led to dismal results, as far as I’m concerned, for the life of the church. I’d be happy to have a conversation with them about that.

As far as the contrast with the 1960s and 1970s, you do see this youthful idealism that says, first, there are things that are seriously wrong with the church and with Christianity as it is understood today; and second, we can do something about it.

Now, it seems to me that if a younger generation isn’t feeling those things there’s something seriously wrong with that generation. I don’t want to discourage younger Evangelicals from shaking their fists in anger at the sins of the church and their passion to want to make a difference.

What I’m concerned about of course, is the hubris that sometimes comes with that. It can make it all about us, and our reformation and our ability to make a change in the world, instead of pointing us to a couple of other realities. And the first of those realities, what we have to remember, is that the moribund, horrible, sinful, selfish, hypocritical, televangelist church, the one who is co-opted by technology and growth and all these things we find despicable is the church that Jesus died for. And it is the church that Jesus is so committed to that he is willing to have his name associated with it, with that church, with that group of people who we all find disgusting and frustrating and aggravating and hypocritical and so nominal.

What I’m concerned about of course, is the hubris that sometimes comes with that. It can make it all about us, and our reformation and our ability to make a change in the world, instead of pointing us to a couple of other realities. And the first of those realities, what we have to remember, is that the moribund, horrible, sinful, selfish, hypocritical, televangelist church, the one who is co-opted by technology and growth and all these things we find despicable is the church that Jesus died for. And it is the church that Jesus is so committed to that he is willing to have his name associated with it, with that church, with that group of people who we all find disgusting and frustrating and aggravating and hypocritical and so nominal.

Earlier you mentioned the current Christian buzzword, “transformation”; another big one now is “discipleship.” We see these emphases in the wider Christian subculture, and again, in parts of the Emergent Church movement. One Emergent pastor I’ve read has said “the gospel is not that Jesus died for your sins, but that God wants you to help him transform the world.” How do you understand transformation for Christians?

We have to maintain a realistic sense of what we mean when we talk about changing things and transforming things: what is it that we can accomplish this side of the kingdom and what can’t we. Because of course, if you enter into the fray with these grandiose notions that you’re going to be able to transform the whole world and your own church, you’re going to run into brick wall after brick wall after brick wall because of original sin. And you’re going to either do one of two things: you’ll either imagine you’re making a difference when you’re really not, just to self-justify your efforts; or you’re going to become so discouraged that you’re going to give up altogether. And neither of those are Christian responses: one is hypocrisy and one is despair.

We have to maintain a realistic sense of what we mean when we talk about changing things and transforming things: what is it that we can accomplish this side of the kingdom and what can’t we. Because of course, if you enter into the fray with these grandiose notions that you’re going to be able to transform the whole world and your own church, you’re going to run into brick wall after brick wall after brick wall because of original sin. And you’re going to either do one of two things: you’ll either imagine you’re making a difference when you’re really not, just to self-justify your efforts; or you’re going to become so discouraged that you’re going to give up altogether. And neither of those are Christian responses: one is hypocrisy and one is despair.

But the Christian always lives by hope, even in the most miserable of situations. Because he lives by Grace, he doesn’t live by his achievements, or his successes. He lives by the call of God on his life. So in that regard, back to your earlier question, this generation is like the generation of the 1960s, very idealistic, very passionate, very activist—but I’d like to bring in this emphasis on grace and humility back to the center.

What place is there for things that we call spiritual disciplines and what do they look like? It seems that the standard program in Evangelicalism is read your Bible more, pray more, journal more, get some accountability and you’ll get better. And you have said in your articles that often people don’t get better, at least not in the way we think, and the more we focus on our problems, the worse they get. How would you respond to the cry for spiritual disciplines? What’s a healthy way to think about that?

In light of the new thinking I’ve been doing recently, I’m having to rethink how I understand that. But I think the way I’d approach it now, the spiritual disciplines are at some level means of grace. God knows that we are weak and foolish and hard-hearted people. And he not only condescends to become human for us, but he uses elements of his creation in order to teach us about who he really is and what our relationship with him really is like. So spiritual disciplines are more about God’s means of helping us grasp what the Gospel is really all about and how he in fact does transform us. But what’s happened to a lot of the spiritual discipline language is that it not about teaching us who God is and how he shapes us, but it’s about getting transformed. It becomes about us.

In light of the new thinking I’ve been doing recently, I’m having to rethink how I understand that. But I think the way I’d approach it now, the spiritual disciplines are at some level means of grace. God knows that we are weak and foolish and hard-hearted people. And he not only condescends to become human for us, but he uses elements of his creation in order to teach us about who he really is and what our relationship with him really is like. So spiritual disciplines are more about God’s means of helping us grasp what the Gospel is really all about and how he in fact does transform us. But what’s happened to a lot of the spiritual discipline language is that it not about teaching us who God is and how he shapes us, but it’s about getting transformed. It becomes about us.

One of Dallas Willard’s earlier works talks about the “spirit of the disciplines,” understanding how God changes lives. And there’s an emphasis that these are classic disciplines that have grown up in the church as a result of the leading of the Holy Spirit that have been instrumental—used by the Holy Spirit—to shape us.

But nowadays, you read books on spiritual formation with titles like “Spiritual Disciplines: Practices that Transform Us” and “Arranging our Lives for Spiritual Transformation.” They’re all about us. And that’s where the emphasis has gone askew in the spiritual discipline world. Jesus, of course, talked about prayer and fasting, and was a regular attender of the synagogue (so he obviously attended worship, he listened to preaching and the reading of scripture). So all these are means by which a person is shaped and formed by God. But that is the point. And they will in fact have that affect. They will shape us and change us. If they don’t, something is fundamentally wrong. But that isn’t why we enter into them or what they’re about when we start them. It’s more about trying to enter into a human work/activity—prayer, Eucharist, preaching, Bible study—that opens us to the wonders of God’s grace.

I heard a sermon once where the preacher said that we need to clear things out of our lives, so that God can come in. And I said “Wait a second, if God wants to come in, He can.”

Exactly. He comes in people’s lives that are pretty darn cluttered.

I don’t think St. Paul cleared the road for Jesus to convert him. But often among Christians we talk about spiritual disciplines as if we are the only actors. But in reality, God is much more interested in your heart and soul than you are, and is probably already doing lots of things that you may or may not be aware of. He is disciplining you spiritually apart from anything you do.

Right. The very fact that you even have any desire to do spiritual disciplines might be a prompting of the Spirit in the first place. You’re not offering something up on your own initiative.

One example might be fasting. People talk about fasting in the terms you’ve talked about—clearing out space in our lives for God to enter in. For me, fasting is a physical parable that reminds me of how much of my life is focused on things that are non-God. Which is probably why I don’t do it very often. Fasting is something that always brings me to my knees in repentance. If it opens me up to God, it’s only because I recognize that I’m a person who’s not very open to God. And I think that’s true of all the disciplines on some level.

Last question: what are the bright spots in the Evangelical world? When you think about the future, what encourages you or gives you hope in light of all the muddled theology out there (a lot of which is pretty depressing)?

Well, I do think the neo-Calvinist movement is a hopeful sign. Everyone, when they talk about what young people are into these days, they’re always pointing to the radical emergent crowd. But when you actually look at the number of young twenty-something people who are actually going to church, or going to conferences, and giving their money to things, a huge number are in the Reformed crowd. I think they’re hungry to hear the message of the sovereignty of God, the prevenience of Grace. All the classical Christian understanding of the world. And the Reformed are really good at making that point. And they’re doing it really well right now.

Well, I do think the neo-Calvinist movement is a hopeful sign. Everyone, when they talk about what young people are into these days, they’re always pointing to the radical emergent crowd. But when you actually look at the number of young twenty-something people who are actually going to church, or going to conferences, and giving their money to things, a huge number are in the Reformed crowd. I think they’re hungry to hear the message of the sovereignty of God, the prevenience of Grace. All the classical Christian understanding of the world. And the Reformed are really good at making that point. And they’re doing it really well right now.

The problem with a lot of the neo-Reformed movement is that they turn Grace—and you read some of the blogs, etc.—they turn Grace into a new Law. And they’re very judgmental and very critical of people who don’t talk about the Gospel in exactly terms they think it should be talked about. And they’re very quick to judge and to cast people off into outer darkness. This is the great weakness of the Neo-Reformed movement, as I can see it. But I nonetheless still think it’s a hopeful sign because it puts the emphasis on the right place: that it’s about God, first and foremost.

The other thing that’s a helpful movement, but could move in one of two directions, is the Ancient-Future movement. When people are trying to draw on the resources of Church historic, especially the early church fathers, and the church tradition that’s found in Catholic and Orthodox (and Anglican) circles, I think that is helpful, as long as it’s not being turned into a new traditional-ism, or it’s turned into a new religion. But drawing on the theological and ecclesial resources that the Church has offered us, that God has given to the church through the ages, has the potential to bring the Evangelical movement a more even keel and a breadth and a depth that could help sustain it in the decades ahead.

Of course, that’s just speaking on human level about two movements I tend to have some hope for. But in fact, in the end I really don’t care if Evangelicalism survives or not, as we know it today. God cares about Evangelicalism as he cares about the nations of the world—they’re a drop in the bucket. He doesn’t need Evangelicalism to further his cause in the world. And if Evangelicalism were to disappear tomorrow, we shouldn’t lose much sleep about it.

Of course, that’s just speaking on human level about two movements I tend to have some hope for. But in fact, in the end I really don’t care if Evangelicalism survives or not, as we know it today. God cares about Evangelicalism as he cares about the nations of the world—they’re a drop in the bucket. He doesn’t need Evangelicalism to further his cause in the world. And if Evangelicalism were to disappear tomorrow, we shouldn’t lose much sleep about it.

But the fact of the matter is that God in history has continued to raise up some group, somehow, somewhere that speaks out the truth of the Gospel in a way that is not only truthful but actually makes a difference in people’s lives. There were no evangelicals in 1500, but then God raised up Luther and John Calvin to remind us of that. There were no Evangelicals per se in 1700 but Whitefield and Wesley came along and started the preaching that led to the Great Awakening.

So the greatest hope I have for the future is what Evangelicals have traditionally stood for—the preaching of the Gospel. I have great hope in that, because God will not desert his church. How will that look? I have no idea. Will evangelicalism fragment? It may. I don’t think it will necessarily, but if it does, God will raise up something else.

COMMENTS

6 responses to “Exclusive Interview: Mark Galli of Christianity Today (pt. 2)”

Leave a Reply

Wow…beautiful. God CAN come in if he wants, we don't have to clear stuff out.

this man gets it. so do you all at mockingbird. thanks!

I loved the interview–thanks!

However, the Neo-Calvinist or any Calvinist movement is cause for alarm as far as Im concerned. Galli appears conflicted about the movement too–he starts by praising it in abstract terms–he thinks it gives glory to God, but then he starts distancing himself from it according to it's particular practice!

What do you think about the Neo-Reformed?

I agree with you Mich, I thought the same thing when I read that part. However, I wonder if he was referring to individuals within the Neo-Reformed who are more into Mike Horton & Tim Keller than John Calvin (not that Calvin was all bad).

Either way, I'd like to commend Aaron on his really thoughtful questions! This is a very readable piece.

* insert 'movement' after the 'Neo-Reformed' part *

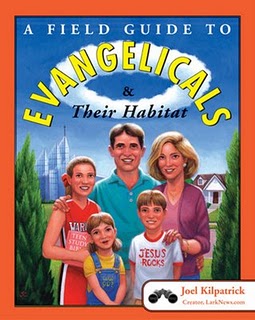

Excellent questions and good comments from Galli. Thanks. Also, the images you guys include (e.g. Transformers logo when talking about spiritual transformation) is that extra touch that makes Mockingbird rule school.